Roofs

A roof is a building’s most important layer of defense against water, wind, and sun. Properly constructed and maintained, a roof deflects rain and snowmelt, and routes them away from other house surfaces. Historically, roof materials have included straw, clay tile, wood, and slate. Although many of these materials are still used, most roofs installed today are asphalt-based composites.

If roofs consisted simply of two sloping planes, covering them would be easy. But today’s roofs have protruding vent pipes, chimneys, skylights, dormers, and the like—all potentially water dams and channels that need to be flashed to guide water around them. Then as runoff approaches the lower reaches of the roof, it must be directed away from the building by means of overhangs, drip-edges, and—finally—gutters and downspouts.

This chapter assumes that the house foundation and framing are stable. Because structural shifting or settling can cause roofing materials to separate and leak, you should fix structural problems before repairing or replacing a roof.

Among the building trades, roofing is considered the most dangerous—not because its tasks are inherently hazardous—but because they take place high above the ground. The steeper the roof pitch, the greater the risk. If heights make you uneasy or if you’re not particularly agile, hire a licensed contractor.

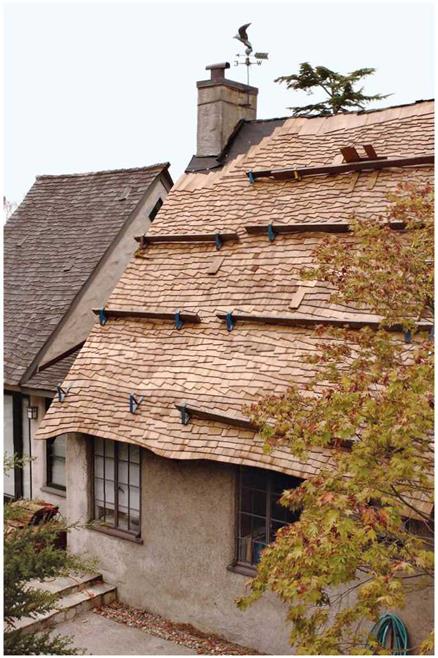

Although these wood shingles seem randomly placed, the installer is taking great pains to offset the shingle joints between courses and to maintain a minimum exposure of 5 in. so the roof would be durable as well as distinctive.

Leave a reply