RESILIENT FLOORING

Vinyl and linoleum are the two principal resilient materials, available in sheets 6 ft. to 12 ft. wide, or as tiles, typically 13 in. or 12 in. square. Linoleum is the older of the two materials, patented in 1863. It may surprise you to learn that linoleum is made from raw natural materials, including linseed oil (oleum lino, in Latin), powdered wood or cork, ground limestone, and resins; it’s backed with jute fiber. (Tiles may have polyester backing.) Because linoleum is comfortable underfoot, water resistant, and durable, it was a favorite in kitchens and baths from the beginning; but it fell into disfavor in the 1960s, when it was supplanted by vinyl flooring, which doesn’t need to be waxed.

However, linoleum has proven resilient in more ways than one by bouncing back from nearextinction, thanks to new presealed linoleums that don’t need waxing. In addition, linoleum (sometimes called Marmoleum®, after the longest continuously manufactured brand) has antistatic and antimicrobial qualities. It’s also possible to custom-design linoleum borders and such, which are then precisely cut with a water jet. Flooring suppliers can tell you more.

Vinyl has similar attributes to linoleum, though it is a child of chemistry. Its name is short for polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Vinyl flooring is also resilient, tough to damage, stain resistant, and easy to clean. It comes in many grades, principally differentiated by the thickness of its top layer—also known as its wear layer. The thicker the wear layer, the more durable the product.

The more economical grades have designs only in the wear layer; whereas inlaiddesigns are as deep as the vinyl is thick. If you’re thinking of installing vinyl yourself, tiles are generally easier, though their many joints can compromise the flooring’s water resistance to a degree.

If stone and tile are properly bonded to a durable substrate, nothing outlasts them. However, handmade tiles or stones of irregular thickness should usually be installed in a mortar bed to adequately support them. And leveling a mortar bed is best done by a professional. Tile or stone that’s not adequately supported can crack, and its grout joints will break and dislodge. Chapter 16 has the full story.

Tiles are rated by hardness: Group III and higher are suitable for floors. Slip resistance is also important. In general, unglazed tiles are less

Tiles are rated by hardness: Group III and higher are suitable for floors. Slip resistance is also important. In general, unglazed tiles are less

slippery than glazed ones, but all tile and stone— and their joints—must be sealed to resist staining and absorbing water. (Soapstone is the only exception. Leave it unsealed because most stone sealers won’t penetrate soapstone and the few that will make it look as if it had been oiled.)

slippery than glazed ones, but all tile and stone— and their joints—must be sealed to resist staining and absorbing water. (Soapstone is the only exception. Leave it unsealed because most stone sealers won’t penetrate soapstone and the few that will make it look as if it had been oiled.)

Tile and stone suppliers can recommend sealants, and you’ll find a handful of good ones in "Countertop Choices,” on p. 313. If stone and tile floors are correctly sealed, they’re relatively easy to clean with hot water and a mild household cleaner.

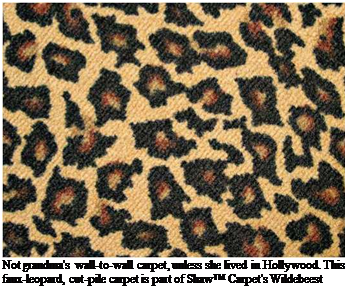

Carpeting is favored in bedrooms, living rooms, and hallways because it’s soft and warm underfoot, and deadens sound. In general, the denser the pile (yarn), the better the carpet quality. Always install carpeting over padding; the denser or heavier the pad, the loftier the carpet will feel and the longer it will last. Wool tends to be the most luxurious and most expensive carpeting, but it’s more likely to stain than synthetics. Good-quality polyester carpeting is plush, stain resistant, and colorfast. Nylon is not quite as plush or as colorfast, though it wears well. Olefin and acrylic are generally not as soft or durable as other synthetics, although some acrylics look deceptively like wool.

Disadvantages: Carpeting can be hard to keep clean, and it harbors dust mites and pet dander, which can be a problem for people with allergies. In general, wall-to-wall carpet is a poor choice for below-grade installations that are not completely dry, because mold will grow on its underside. Far better to use throw rugs in finished basement rooms.

Leave a reply