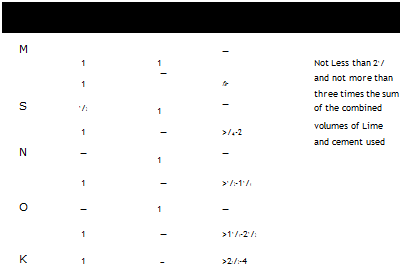

Mortar Types (ASTM C 270-68)*,t

TWO WAYS TO CUT BRICK

TWO WAYS TO CUT BRICK

|

Using a mason’s hammer, score all the way around the brick, then strike the scored lines sharply. Such cuts will be more accurate if you place the bricks on a bed of sand. |

Mortar will remain usable for about 2 hours, so mix only about two buckets at a time. If the batch seems to be drying out, “temper” it by sprinkling a little water on the batch and turning it over a few times with a trowel. As you seat each course of bricks in mortar, use the trowel to gently scrape excess mortar from joints and throw it back into the pan or onto the mortarboard. Periodically turn that mortar back into the batch so it doesn’t dry out. Don’t reuse mortar that drops on the ground.

Trowel techniques. Hold a trowel with your thumb on top of the handle—not on the shank or the blade. This position keeps your thumb out of the mortar, while giving you control. Wrap your other fingers around the handle in a relaxed manner.

There are two basic ways to load a trowel with mortar. The first is to make two passes: Imagine that your mortar pan is the face of a clock. With the right-hand edge of the trowel raised slightly, take a pass through the mortar from 6:30 to 12:00. Make the second pass with the left-hand side of the blade tipped up slightly, traveling from 5:30 to 12:00. According to master mason and author Dick Kreh, a trowelful of mortar should

|

|

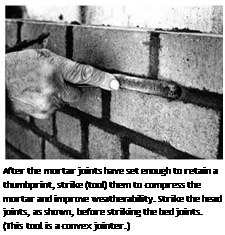

As you turn the trowel to unload the mortar, pull it toward you quickly, thus stringing the mortar in a line.

resemble "a long church steeple, not a wide wedge of pie.”

The second method is to hold the trowel blade at an angle of about 80° to the mortarboard. Separate a portion of mortar from the main pile and, with the underside of the trowel blade, compress the portion slightly, making a long, tapered shape. To lift the mortar from the board, put the trowel (blade face up) next to the mortar, with the blade edge farthest away slightly off the board. With a quick twist of the wrist, scoop up the mortar. This motion is a bit tricky: If the mortar is too wet, it will slide off.

To unload the mortar, twist your wrist 90° as you pull the trowel toward you. This motion spreads, or strings, the mortar in a straight line.

It is a quick motion, at once dumping and stringing out the mortar, and it takes practice to master. If you are laying brick, practice throwing mortar along the face of a 2×4, which is about the same width as a wythe of brick. Each brick course gets a bed of mortar as wide as the wythe.

After you’ve strung out the mortar, furrow it lightly with the point of the trowel to spread the mortar evenly. Trim off the excess mortar that hangs outside the wythe, and begin laying brick.

Laying brick. If the first course is at floor level (rather than midway up a wall), snap a chalkline to establish a baseline. Otherwise, align new bricks to existing courses.

Throw and furrow a bed of mortar long enough to seat two or three bricks. If you’re filling in an opening, "butter” the end of the first brick, to create a head joint, as shown in the bottom left photo at right. Press the brick into position and trim away excess mortar that squeezes out. Both bed and head joints are ’/2 in. to 58 in. thick until the brick is pressed into place, with a goal of compressing the joint to about 58 in. thick.

Use both hands as you work: One hand maneuvers the bricks, while the other works the trowel, scooping and applying mortar and tapping bricks in place with the trowel handle. If you use a stringline to align bricks, get your thumb out of the way of the string just as you put the brick into the mortar bed. As you place a brick next to one already in place, let your hand rest on both bricks; this gives you a quick indication of level.

When you have laid about six bricks in a course, check for level. Leaving the level atop the course, use the edge of the trowel blade to tap high bricks down—tap the bricks, not the level. Tap as near the center of the bricks as the level will allow. If a brick is too low because you have scrimped on mortar, it’s best to remove it and reapply the mortar.

Next plumb the bricks, holding the level lightly against the bricks’ edges. Using the handle of the trowel, tap bricks till their edges are plumb. (Hold the level lightly against the brick, but avoid pushing the level against the face of the brick.) Finally, use the trowel handle to tap bricks forward or back so that they align with a mason’s line or a level held lightly across the face of the structure

The last brick in a course is called the closure brick. Butter both ends of that brick liberally and slide it in place. The bed of mortar should also be generous. As you tap the brick into place with the trowel handle, scrape excess mortar off, ensuring a tight fit. If you scrimp on the mortar, you may need to pull the brick out and remortar it, perhaps disturbing bricks nearby.

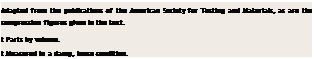

Striking joints. Striking the mortar joints, also called tooling the joints, compresses and shapes the mortar. Typically, a mason will strike joints every two or three courses, before the mortar dries too much. To test the mortar’s readiness for striking, press your finger into it. If the indentation stays, it’s ready to strike. If the mortar’s not reading for striking, wet mortar will cling to your finger and won’t stay indented.

Use a jointer to strike joints. First strike the head joints and then the bed joints. The shape of the joint determines how well it sheds water. As suggested in "Mortar Joints,” joints that shed water best include concave (the most common), V-shaped, and weathered joints. Flush joints are only fair at shedding water. Struck, raked, and extruded joints shed poorly because they have shelves on which water collects.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|||

Leave a reply