Masonry

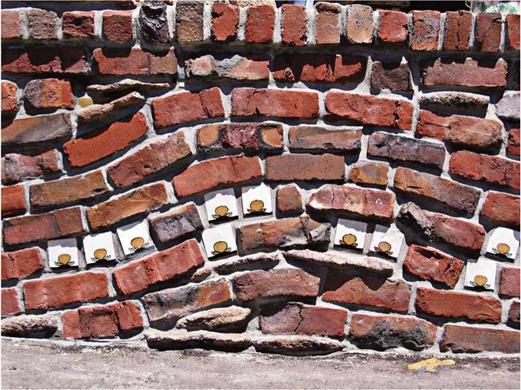

|

|

Modern masonry

materials, including stone, brick, tile, concrete, and other minerals that become strong and durable when used in combination. The craft of masonry is ancient. The oldest surviving buildings are stone, but stone is heavy and difficult to work with. Brick, on the other hand, is less durable than stone but lighter and easier to lay up. And clay, the basic component of brick, is found almost everywhere.

Technologically, the switch from stone to brick was a great leap in several respects. First, masons began with a plastic medium (mud and straw) that they shaped into hard and durable building units of uniform size. Second, brickmaking is one of the earliest examples of mass production. Third, basic bricklaying tools, such as trowels, were so perfectly designed that they’ve changed little in 4,000 or 5,000 years.

Unless otherwise specified, mixes and methods in this chapter are appropriate for brickwork as well as concrete-block work. But most of this chapter is about brick and poured concrete because concrete – block work is uncommon in renovation.

Here’s a handful of mason’s lingo that’s frequently confused:

Portland cement. The basic component of all modern masonry mixtures. When water is added to cement, it reacts chemically with it, giving off heat and causing the mix to harden, thus bonding together materials in contact with the mix. By varying the proportions of the basic ingredients of a concrete mix, the renovator can alter the concrete’s setting time, strength, resistance to

certain chemicals, and so on. Portland cement is available in 94-lb. bags.

certain chemicals, and so on. Portland cement is available in 94-lb. bags.

Masonry cement. Also called mortar cement, a mix of portland cement and lime, although exact proportions vary. The lime plasticizes the mix and makes it workable for a longer period. Once dry, the mix is also durable.

Aggregate. Material added to a concrete mix. Fine aggregate is sand. Coarse aggregate is gravel. Concrete aggregate is typically 14-in. gravel, unless specifications call for pea gravel (58-in. stone).

Mortar. Used to lay brick, concrete block, stone, and similar materials. As indicated in "Mortar Types,” on p. 187, mortar is a mixture of masonry cement and sand or of portland cement, lime, and sand. It’s usually available in 60-lb. bags.

Grout. A mix of portland cement and sand or of masonry cement and sand. Mixed with enough water so it flows easily, grout is used to fill cracks and similar defects. In tiling, grout is the cementitious mixture used to seal joints.

Concrete. A mixture of water, portland cement, sand, and gravel. Supported by forms until it hardens, concrete is afterward a durable, monolithic mass.

Reinforcement. The steel mesh or rods embedded in masonry materials (or masonry joints) to increase resistance to tensile, shear, and other loads. In concrete, the term usually refers to steel rebar (reinforcement bar), which strengthens foundations against excessive lateral pressures exerted by soil or water.

Admixtures. Mixtures added to vary the character of masonry. They can add color, increase plasticity, resist chemical action, extend curing time, and allow work in adverse situations. Admixtures are particularly important when ordering concrete, because mixes may contain water reducers, curing retardants, accelerants, air entrainers, and a host of other materials that affect strength, curing times, and workability.

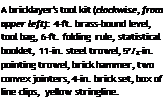

and shape mortar joints. A good-quality trowel has a blade welded to the shank. Cheap trowels are merely spot welded. Bricklayer’s trowels tend to have blades that are 10 in. to 11 in. long. Pointing trowels, which look the same, have blades roughly 5 in. long; they’re used to shape masonry joints. Margin trowels are square- bladed utility trowels used for various tasks.

Jointers (striking irons) compress and shape mortar joints, some of which are shown in "Mortar Joints,” on p. 189. The most common are bullhorn jointers, shown in the photo on p. 190, and convex jointers, shown in the photo above. The half-round, concave mortar joint they create sheds water well.

Tuck-pointing trowels are narrow-bladed trowels (usually the width of a mortar joint, 58 in.) used to repoint joints after old mortar has been cut back. Because it packs and shapes mortar, this tool is both trowel and jointer and has more aliases than an FBI fugitive: tuck-pointing trowel, jointing tool, repointing trowel, striking slick, slicker jointer, slicker, and slick.

Tuck-pointing chisels partially remove old mortar so joints can be repointed (compacted and shaped) to improve weatherability. Angle grinders and pneumatic chisels also remove mortar.

Tuck-pointing chisels partially remove old mortar so joints can be repointed (compacted and shaped) to improve weatherability. Angle grinders and pneumatic chisels also remove mortar.

Leave a reply