Installation, in a Nutshell

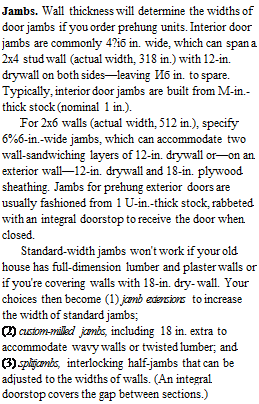

Today, most doors, windows, and skylights are preassembled in factories and delivered preframed, which makes installation much easier. Basically, you screw or nail the unit’s squared frame to a rough opening (RO). If the opening is in an exterior wall, weatherproof it first-wrap, flash, and caulk. Rough openings are typically Уг in. to 1 in. wider and taller than the outside dimension of the door or window frame being installed.

However, rough openings are rarely square or perfectly sized, so you need to insert shims (thin, tapered pieces of wood) between the square frame and the out-of-square opening. Shimming takes patience. But if you install shims well, doors, windows, and skylights will operate freely, without binding. Once a preframed window or door is installed in its RO, insulate or spray foam between the frame and the RO to further block moisture and drafts. Then cover those gaps with casing (or trim) inside and out.

In general, avoid precased units, which have casing preattached to frames. It’s difficult to shim between the frame and the rough opening if casing’s in the way.

As you level and plumb windows and doors, use pairs of taperec shims to hold units in the rough openings. Use trim-head screw when tacking frames. They are easier to remove when adjusting shims and less likely to bend than finish nails. And their small heads are easy to sink, fill, or cover with a stop.

|

|

|

Height. Standard door height is 6 ft. 8 in., for both interior and exterior doors on newer houses. Older houses (1940s and earlier) sometimes had doors 7 ft. high, so that size is still widely available. Of late, 8-ft.-high French doors are in vogue. Of course, you can special-order a door of virtually any size if you’re willing to pay enough. Salvage yards are excellent sources of odd-size doors.

Swing. Door swing indicates which side you want the hinges on. Imagine facing the door as it swings open toward you: If the door knob will hit your right hand first, it’s a righthanded door; if your left hand grabs the knob, then it’s a lefthanded door.

Type and style. Hinged single doors are by far the most common type, but they need room to operate. If space is tight, consider sliding doors, pocket doors, or bifolds. For wide openings, note that hinged double-doors individually weigh less and take less room to swing open than one massive door.

Try to match existing doors or those on houses of similar architectural periods. In general, frame-and – panel doors tend to go well with older houses; whereas flush doors have a more contemporary look. For that reason, sliding doors on older homes are usually placed on the back side of the house so they don’t look inconsistent with the front and side facades.

![]()

Construction and materials. For exterior doors, wood is the traditional favorite, but it requires a lot of maintenance. Consequently, wood doors come clad in vinyl or aluminum, and good-quality, insulated steel doors are virtually indistinguishable from wood once they’re painted. Fire codes require steel doors between living spaces and attached garages or workshops. Exterior doors should have integral weatherstripping.

Construction and materials. For exterior doors, wood is the traditional favorite, but it requires a lot of maintenance. Consequently, wood doors come clad in vinyl or aluminum, and good-quality, insulated steel doors are virtually indistinguishable from wood once they’re painted. Fire codes require steel doors between living spaces and attached garages or workshops. Exterior doors should have integral weatherstripping.

Given the rise of engineered lumber, it’s not surprising that many doors—both interior and exterior—are now made from plywood, hard – board, and so on. They can be stamped to mimic traditional panel doors and insulated to deaden sound and retain heat. They paint up nicely, can be cost-effective, and are generally more stable than solid wood.

Weatherstripping and glazing. Weatherstripping on exterior doors is often rabbeted into jambs, so it’s tighter and more energy efficient than anything you could install later. There is also a variety of thresholds and door bottoms available to keep snow or rain out, or to clear water so it doesn’t soak and destroy the bottom of the door.

If your exterior door has glass panels, they should be double glazed at the least; triple glazing is more energy efficient but costs more. Double glazing and a storm door may be a better choice. Finally, prefinish exterior doors with a UV – and water-resistant finish; at the very least, prime or seal all six sides.

Hardware. Hardware for prehung doors is preinstalled at the factory; then locksets and door handles are removed to prevent damage during shipping.

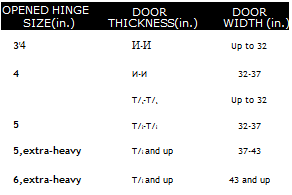

As indicated in "Sizing Hinges,” below, hollow – core or solid-wood interior doors up to 158 in. thick can be supported by two 352-in. by 352-in. (opened size) hinges; whereas 1 52-in.-thick exterior doors

Sizing Hinges

usually require three 4-in. by 4-in. hinges. Extraheavy exterior doors may need even bigger hinges or hinges with ball bearings or grease fittings.

As shown in "Mortise Lockset,” on p. 103, and "Cylinder Lockset,” on p. 105, exterior locksets are most often cylinder locks, which require a 258-in. hole drilled into the face of the door, or mortise locks, which are housed in a rectangular mortise cut into the latch edge of the door. Mortise locks are more expensive and difficult to install, so they are most often used only on entry doors, with a thumb-lever handle. For added security, supplement exterior door locksets with a dead bolt and a reinforced strike plate.

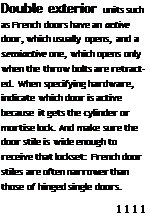

Double exterior doors may have interconnected locksets, and flush bolts or surface bolts. Interior locksets are almost always some kind of cylinder lock: passage locks or latch sets on doors that don’t need to be locked and privacy locks or locksets on doors that do need locking, such as bedroom doors. Bathroom locks are specialized locksets with a chrome bathroom-facing knob to match plumbing fixtures.

Leave a reply