Framing with Steel

The use of steel framing in residential renovation is increasing, but it’s still rare and generally not advised for novice builders unless working with a builder experienced with it.

Light steel framing consists primarily of C – shaped metal studs set into U-shaped top and bottom plates, joined with self-drilling pan-head screws. Fast and relatively cheap to install, light steel framing (20 gauge to 25 gauge) is most often used to create non-load-bearing interior partitions in commercial work.

Its advocates argue that more residential contractors would use it if they were familiar with it. In fact, light steel framing is less expensive than lumber; it can be assembled with common tools, such as aviation snips, screw guns, and locking pliers; and it’s far lighter and easier to lug than dimension lumber. To attach drywall, use type-S drywall screws instead of the type W screws specified for wood.

If you want to hide a masonry wall, light steel framing is ideal. Masonry walls are often irregular, but if you use 158-in. metal framing to create a wall within a wall, you’ll have a flat surface to drywall that’s stable and doesn’t eat up much space.

That said, light steel is quirky. You must align prepunched holes for plumbing and wiring before cutting studs and, for that reason, you must measure and cut metal studs from the same end. If you forget that rule, your studs become scrap. Finally, if you want to shim and attach door jambs and casings properly, you need to reinforce steel-framed door openings with wood.

Flitch plates are steel plates sandwiched between dimension lumber and are through-bolted to increase span and load-carrying capacity. Flitch plates are most often used in renovation where existing beams or joists are undersize. (You insert plates after jacking sagging beams.)

Ideally, a structural engineer should size the flitch plate assembly, including the size and placement of bolts. Steel plates are typically 58 in. to 58 in. thick; the carriage bolts, 58 in. to 58 in. in diameter. Stagger bolts, top to bottom, 16 in. apart, keeping them back at least 2 in. from beam

|

STEEL FRAMING |

Load-bearing steel framing is heavier (14 gauge to 20 gauge) and costs much more than lumber. Plus it requires specialized tools and techniques. Metal conducts cold, so insulating steel walls can be a challenge. For exterior and loadbearing walls, you’re better off with wood framing.

edges. Put four bolts at each beam end. To ease installation, drill bolt holes 58б in. wider than the bolt diameters.

Flitch plates run the length of the wood members. The wood sandwich keeps the steel plate on edge and prevents lateral buckling. Note: Bolt holes should be predrilled or punched—never cut with an acetylene torch. That is, loads are transferred partly through the friction between the steel and wood faces, thus the raised debris around acetylene torch holes would reduce the

desired steel-wood contact.

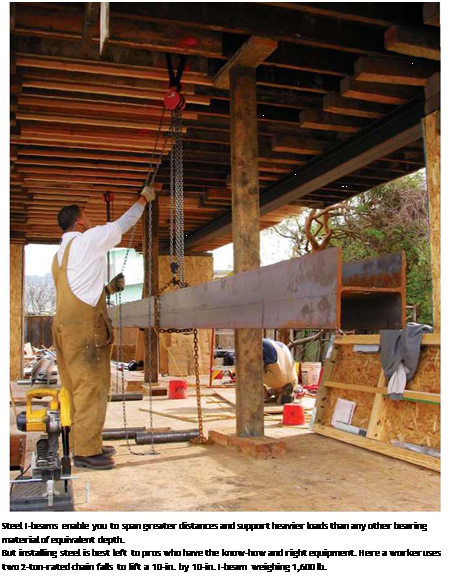

Although lately eclipsed by engineered-wood beams, steel I-beams, for the same given depth, are stronger. Consequently, steel I-beams may be the best choice if you need to hide a beam in a relatively shallow floor system—say, among 2 x6s or 2x8s—or if clearance is an issue.

Wide-flange I-beams are the steel beams most commonly used in residences, where they typically range from 4’h in. to 10 in. deep and 4 in. to 10 in. wide. Standard lengths are 20 ft. and 40 ft., although some suppliers stock intermediate sizes. Weight depends on the length of the beam and the thickness of the steel. That is, a 20-ft.,

![]()

![]()

8×4 I-beam that’s 0.245 in. thick weighs roughly 300 lb.; whereas, a 20-ft., 8x8H I-beam with a web that’s 0.458 in. thick weighs 800 lb. If you order a nonstandard size, expect to pay a premium.

8×4 I-beam that’s 0.245 in. thick weighs roughly 300 lb.; whereas, a 20-ft., 8x8H I-beam with a web that’s 0.458 in. thick weighs 800 lb. If you order a nonstandard size, expect to pay a premium.

Before selecting steel I-beams, consult with a structural engineer. For installation, use a contractor experienced with these beams. Access to the site greatly affects installation costs, especially if there’s a crane involved.

Leave a reply