Foundations and Concrete

Foundation issues

Foundation issues

before starting extensive remedial work, such as replacing failed foundation sections or adding a second story to your house, have a structural engineer evaluate your foundation. In addition, bring in a soils engineer if the site slopes steeply or if the foundation shows any of the following distress signs: bowing, widespread cracking, uneven settlement, or chronic wetness. Engineers can also assess potential concerns such as slide zones, soil load-bearing capacity, and seasonal shifting.

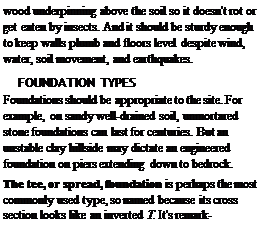

A foundation is a mediator between the loads of the house and the soil on which the foundation rests. A well-designed foundation keeps a house’s

|

ably adaptable. On a flat site in temperate regions, a shallow tee foundation is usually enough to support a house, while creating a crawl space that allows joist access and ventilation.

Where the ground freezes, foundation footings need to be dug below the frost line, stipulated by local codes. Below the frost line, footings aren’t susceptible to the potentially tremendous lifting and sinking forces of freeze-thaw cycles in moist soil. (Thus most houses in cold climates often have full basements.)

When tee foundations fail, they often do so because they’re unreinforced or have too small or too shallow a footprint. Unreinforced tee foundations that have failed are best removed and replaced. But reinforced tees that are sound can be underpinned by excavating and pouring larger footings underneath a section at a time.

Slab on grade is a giant pad of reinforced concrete, poured simultaneously with a slightly thicker perimeter footing that increases its loadbearing capabilities. Beneath the slab, there’s typically a layer of crushed gravel and sheet plastic over that to prevent moisture from wicking up from the soil. Slabs are generally installed on flat lots where the ground doesn’t freeze because, being above frost line, shallow slabs are vulnerable to frost heaves. Although shallow, the large footprint of a slab sometimes makes it the only feasible foundation on soils with weak load-bearing capacity. Because slabs sit on grade, their drainage systems must be meticulously detailed.

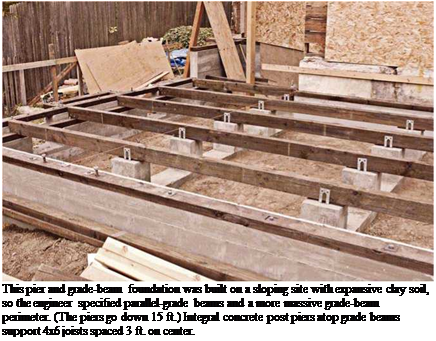

Drilled concrete piers in tandem with grade beams are the premier foundation for most situations that don’t require basements. These foundations get their name because pier holes are typically drilled to bearing strata. This foundation type is unsurpassed for lateral stability, whether as replacement foundation for old work or for new construction. Also, concrete piers have a greater cross section than driven steel piers and hence greater skin friction against the soil, so they’re much less likely to migrate. The stability of concrete piers can be further enhanced by concrete-grade beams resting on or slightly below grade, which allow soil movement around the piers, without moving the piers.

The primary disadvantages of drilled concrete piers are cost and access. In new construction, a backhoe equipped with an auger on the power takeoff requires 10 ft. or 12 ft. of vertical clearance. Alternatively, there are remote-access portable rigs that can drill in tight quarters, even inside existing houses, but they are labor intensive to set up and move, increasing the cost.

Driven steel pilings are used to anchor foundations on steep or unstable soils. Driven to bedrock and capped, steel pilings can support heavy vertical loads. And, as retrofits, they can stabilize a wide range of problem foundations. There are various types of steel pilings, including helical piers, which look like giant auger bits and are screwed in with hydraulic motors, and push piers, which are hollow and can be pushed in, strengthened with reinforcing bar, and filled with concrete or epoxy.

Driven steel pilings are used to anchor foundations on steep or unstable soils. Driven to bedrock and capped, steel pilings can support heavy vertical loads. And, as retrofits, they can stabilize a wide range of problem foundations. There are various types of steel pilings, including helical piers, which look like giant auger bits and are screwed in with hydraulic motors, and push piers, which are hollow and can be pushed in, strengthened with reinforcing bar, and filled with concrete or epoxy.

Leave a reply