Engineered Lumber

Like any natural product, standard lumber is quirky. It has knots, holes, and splits. And it twists, cups, and shrinks. As mature old-growth timber was replaced by smaller, inferior trees, lumber quality became less reliable—much to the dismay of builders.

In response, the lumber industry combined wood fiber and strong glues to create engineered lumber (EL), including I-joists, engineered beams, plywood, and particleboard. EL spans greater distances and carries heavier loads than standard lumber of comparable dimensions. In addition, EL won’t shrink and remains straight, stable, strong and—above all—predictable.

Still, EL has two main drawbacks: It’s heavy, so dense that it must often be predrilled, and it costs considerably more than sawn lumber. Even so, EL is here to stay.

![]()

The most common truss is the prefabricated roof truss, which is a large triangular wood framework that serves as the roof’s support structure. Its short web-like reinforcing members are fastened by steel truss plates. Trusses are lightweight, cheap, quick to install, and strong relative to the distances they span. Thus they eliminate the need for deep-dimensioned traditional roof rafters and complex cutting.

► Advantages: Trusses can be prefabricated for almost any roof contour, trucked to the job site, and erected in a few days. In addition, you can route ducts, pipes, and wiring through openings in the webbing—a great advantage in renovation work.

► Disadvantages: Roof trusses leave little living space or storage space in the attic.

Adding kneewalls on the sides will gain some height, but your design options will be limited. Roof trusses should be engineered and factory built and never modified, unless an engineer approves the changes; otherwise, unbalanced loads could cause the trusses—and the roof— to fail.

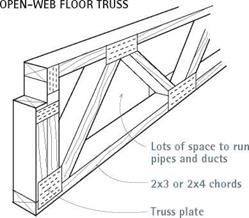

Floor trusses, on the other hand, are often open webs spaced 24 in. on center. Although their spanning capacities are roughly the same as I-joists of comparable depth, it’s much easier to run ducts, vents, wiring, and plumbing through open-web trusses.

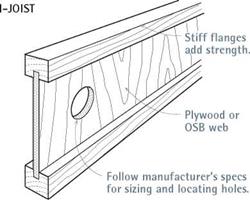

I-joists are commonly called TrusJoists®, after a popular brand (now a subsidiary of Weyerhaeuser®). Typically, I-joists are plywood or OSB (oriented strand board) webs bolstered by stiff lumber flanges top and bottom, which add strength and prevent lateral bending.

Although I-joists look flimsy, they are stronger than solid-lumber joists of comparable dimensions. Whereas solid joists are spaced 16 in. on center, I-joists can be laid out on 19h-in. or 24-in. centers. They are also lightweight, straight, and stable. Floors and ceilings constructed with I-joists stay flat because there’s virtually no I-joist shrinkage; hence almost no drywall cracks, nail pops, or floor squeaks.

Installing I-joists is not much different from installing 2x lumber, but blocking between I-joists is critical. (They must be perfectly perpendicular to bear loads.) You can drill larger holes in I-joist webs than you can in solid lumber, but religiously follow manufacturer guidance on hole size and placement. And never cut or nail into I-joist flanges.

D Lumber BUYING

Manufacturers continue to develop more economical I-joist components. Webs may be plywood, particleboard, or LVL (laminated veneer lumber). Flanges have been fabricated from LVL, OSB or—back the future!—solid lumber (2x3s or 2x4s) finger-jointed and glued together. I-joists with wider flanges are less likely to flop and fall over during installation. Plus they offer more surface to glue and nail subflooring to.

Leave a reply