DOUBLE-CHECK YOUR DESIGN

Design is a process of continuing revision that doesn’t stop until you have finished architectural drawings, if then. The closer you get to a design that works, the more information you need. Once you have a floor plan that satisfies most of your program requirements, double-check the assumptions underlying your design. Then revisit your local planning department with your proposed floor plan superimposed on your lot and with elevations or a model. Make sure you ask detailed questions about anything that seems unclear.

Remember, the more specific information you bring to the planner, the better feedback you’ll

get. You can save yourself a lot of backtracking if you confirm that officials will allow you to do the renovations as designed and that you can afford to continue. Make sure you understand the approval process. Many communities require design review or other approvals before you can even apply for a building permit. If you will be living in the house while working on it, get a temporary certificate of occupancy (C. O.).

The same principle applies when discussing construction costs with a contractor. Though you may not yet have the working drawings required for a detailed estimate, you’ll have enough to confirm ballpark costs with a reputable contractor. If you have floor plans and elevations or a model, you are about one-third of the way through the design process.

Once you’ve reconsidered layouts in light of the constraints noted above, proceed to working drawings, which should include accurately drawn floor plans and elevations. Details required for these drawings depend on several variables, the most important being how big the job is and who’s doing the work. A conscientious, experienced builder who practices sound construction and knows code requirements can usually intuit what needs doing even if drawings lack occasional details.

In addition, final drawings are essential because (1) the contractor needs them to give you a solid estimate; (2) they help the contractor anticipate problems and suggest changes before scheduling subcontractors; (3) lenders require them; and (4) many municipalities require tight drawings before issuing work permits—that is, in most communities, both planning and building departments review plans.

How detailed should finished drawings be?

As a minimum, building departments require a cross section from foundation to roof so they can see how the building is framed, insulated, sheathed, and finished. Thus if the job is complex—say, a major kitchen remodeling or more than one room—hire an architect to create a set of working drawings. Because construction documents are usually 40 percent to 50 percent of an architect’s total fee, and that fee is customarily 10 percent to 15 percent of total costs, figure that working drawings with floor plans, elevations, and cross sections will be roughly 5 percent of your total budget.

For handy reference, here’s a step-by-step review of important planning considerations. It begins by reiterating planning steps and then presents a typical sequence for construction.

1. Make wish lists, and analyze what works and what doesn’t in the existing house. Keep a renovation notebook. Then consider how well your designs will satisfy your wish list.

2. Measure rooms, noting the location and condition of the structure and utility systems. Map the site, and consider how well exterior design changes fit the neighborhood.

3. Consider physical and financial constraints. Talk to a contractor about renovation costs. Get preliminary approval on financing.

Visit your local planning department.

4. Generate design variations. As favorites emerge, compare them to your wish list and to any constraints. Rework designs until you settle on one.

5. Double-check your design. Revisit the planning department with floor plans and either elevation drawings or a cardboard model.

6. Prepare permit plans and obtain permits. In most communities, the permit process consists of two steps (planning permits and building permits). If you will be living in the house while working on it, get a temporary C. O.

7. Prepare working drawings. List in detail all building components, assemblies, materials, and finishes.

8. Obtain bids from contractors, and select one. The more detail you give bidders, the more realistic and accurate the bids will be.

Be prepared to continue making design decisions as work proceeds. No matter how detailed your plans, you’ll need to make adjustments as you renovate. The order in which you complete tasks also depends on the coordination of subcontractors. Here’s a typical sequence, if such a thing exists.

1. Clean up. Clean out debris and add rough weather-proofing to gaping holes. Organize the site for efficient work flow.

2. Secure the building so you can store materials and, if necessary, live there.

3. Install temporary facilities such as electrical field receptacles and chemical toilets; hook up temporary utilities.

4. Handle major structural work in the basement or crawl space, repairing damage and flaws that could cause further settling. Correct water problems that could threaten the structure.

5. Replace or replumb posts, columns, girders, and joists that have deteriorated.

6. Demolish walls, ceilings, and floors, and remove debris as it accumulates. If you’re not living in the house, install temporary facilities before you start demolition.

7. Do necessary structural carpentry, such as altering load-bearing walls, joists, headers, and collar ties.

8. Attend to the roof as soon as practical.

(But make structural changes first, because they could undermine the integrity of a finished roof.)

9. Install windows, doors, and exteriors.

10. Erect interior partitions, the nonbearing walls not framed earlier.

11. Rough out heating, plumbing, gas, and electrical systems (no fixtures yet). Install insulation.

12. Hang wall and ceiling surfaces such as drywall.

13. Install underlayment for finish floors; apply tile floors.

14. Set plumbing fixtures and radiators for baseboard heat, wire electrical receptacles, and so on.

15. Finish taping drywall.

16.

![]()

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

17. Paint and wallpaper. (Some renovators do this after trim is in place.)

18. Repair and replace trim around windows and doors. Hang doors, and finish all interior woodwork.

19. Finish floors.

20. Install final details, such as baseboard trim, interior doors, electrical outlet plates, hardware, and floor registers.

Renovation is rarely an easy road. Even the happy endings can take more time and money than owners thought they had. Renovation also requires the courage to start and then the stamina to stay with it.

The renovators: Martha Rutherford, an educator, loved traveling and collecting indigenous art. Her husband, Dean, a contractor, had lived for six years in Latin America before deciding that the priesthood was not for him.

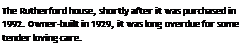

The house: Two-story, owner-built box was erected in 1929. The builder’s widow finally moved on in 1992, after spending most of the previous decade in the living room with four Dobermans, a goat, and a duck. The animals rarely went outside. Dean and Marty stepped carefully into the gloomy interior (the ceiling was painted black), looked at the living room, looked at each other, looked at their real estate agent, and said, "We’ll take it.”

What worked: Location, location, location. Marty is a city gal, Dean a country boy. The wooded site in the Berkeley hills allowed them to live near a major metropolitan area and yet be in the country. But the decision to buy was more mystical than rational.

What didn’t work: The widow had abandoned the bottom floor because it had a year-round stream running through it. The northwest corner of the house was completely gone. The kitchen floor joists were so sodden they were spongy, and the bathroom had rotted out. Between every pair of rafters was a rat’s nest. A beehive blocked the furnace flue. Dean: "I guess the house brought out my seminarian training—you know, salvation and all.”

Constraints:

► Dean had just 3 months to get the house habitable before resuming his construction business full-time.

► The Rutherfords were determined to live within their means, so the renovation would need to stretch over several years.

► Although neighbors were delighted that the property would finally be fixed up, they were wary of the job’s scope and impact.

The plan:

► Stabilize the structure.

► Add a third story to gain views of the setting and give the house street appeal.

► Open it up: "We wanted a house totally open to the outdoors, with a deck off almost every room."

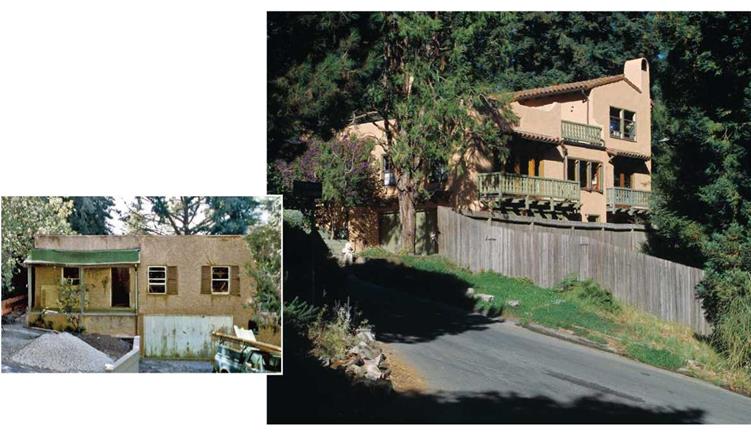

Compromises: Initially, color was a source of conflict. Because her mother had been a painter, Marty grew up surrounded with vibrant colors. Having spent years in monastic settings, Dean had grown up, as he terms it, "in a white world” and feared that Marty’s saturated colors would absorb light and darken the interior, but agreed to them anyway.

Surprises: Because Marty and Dean entered no farther than the living room when they committed to buying the house, the structural problems were a shock. Yet, for Dean the biggest pleasant surprise may have been the colors Marty felt so passionate about. As the two added skylights, opened walls, and installed French doors, they

|

|

Leave a reply