Damp Basement Solutions

To find the best cure for a damp basement, first determine whether the problem is caused by water outside migrating through foundation walls or by interior water vapor inside condensing on the walls. To determine which problem you have, duct tape a 2-ft.-long piece of aluminum foil to the foundation, sealing the foil on all four sides. Remove the tape after 2 days. The wet side of the foil will provide your answer. Chapter 14 has more about mitigating moisture and mold.

If the problem is condensation, start by insulating cold-water pipes, air-conditioning ducts, and other cool surfaces on which water vapor might condense. Wrap pipes with preformed foam pipe insulation. Wrap ducts and larger objects with sheets of vinyl-faced fiberglass insulation, which is well suited to the task because vinyl is a vapor barrier. Use duct tape or insulation tape to seal seams.

Next install a dehumidifier to remove excess humidity. For best results, install a model that can run continuously during periods of peak humidity; place it in the dampest part of the basement at least 12 in. away from walls or obstructions. To prevent mold from growing in the unit’s collection reservoir, drain it daily and scrub it periodically.

Survey the basement for other sources of humidity. An unvented clothes dryer pumps gallons of water into living spaces; vent it outdoors. Excessive moisture from undervented kitchens and bathrooms on other floors can also migrate to the basement; add exhaust fans to vent them properly. Finally, weatherstrip exterior doors and keep them closed in hot, humid weather.

DAMPNESS DUE TO EXTERIOR WATER

Position and maintain gutters and downspouts so they direct water away from the house. And, if possible near affected walls, slope soil away from the house.

Besides those two factors, water that migrates through foundation walls or floors is more elusive and expensive to correct. Basically, you have three remedial options: (1) remove water once it gets in; (2) fill interior cracks, seal interior surfaces, and install a vapor barrier; and (3) excavate foundation walls, apply waterproofing and improve drainage.

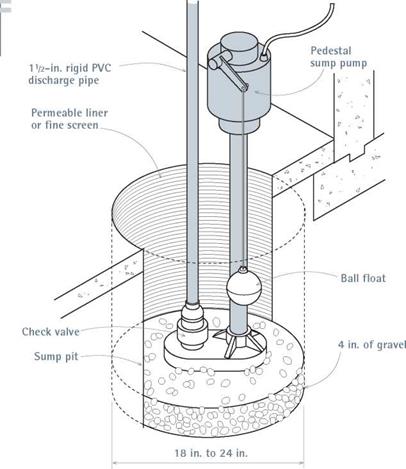

Option one: Remove water. Sump pumps are the best means of removing water once it gets

into a basement. If you don’t have a sump pump, you’ll probably need to break through the basement floor at a low point where water collects, and dig a sump pit 18 in. to 24 in. across. Line the pit with a permeable liner that allows water to seep in while keeping soil out, and put 4 in. of gravel in the bottom.

There are two types of sump pumps. Pedestal sump pumps stand upright in the pit. They are water cooled and have ball floats that turn the pump on and off. Submersible sump pumps, on the other hand, have sealed, oil-cooled motors, so they tend to be quieter, more durable, and more expensive. And because they are submerged, they allow you to cover the pit so nothing falls in. A й-hp pump of either type should suffice.

The type of discharge pipe depends on whether the pump is a permanent fixture or a sometime thing. Permanent pumps should have 112-in. rigid PVC discharge pipes with a check valve near the bottom to prevent expelled water from siphoning back down into the pit. If the water problem is seasonal, many people simply attach a 50-ft. garden hose and run it out a basement window. In either case, discharge the water at least 20 ft. from the house, preferably downhill and not directly into a neighbor’s property.

Option two: Interior solutions. If basement walls are damp, try filling cracks as suggested on p. 205 and applying damp-proofing coatings. (However, this approach won’t work if the walls are periodically wet. After scrubbing the basement walls, parge (trowel on) a cementitious coating such as Thoroseal® Foundation Coating or Sto Watertight Coat® or a polymer-modified system such as Bonsal’s Surewall®. These coatings can withstand higher hydrostatic pressures than elastomeric paints or gels. Epoxy-based coatings also adhere well but are so expensive that they’re usually reserved for problem areas such as wall to floor joints.

To further control moisture diffusion through the walls, install a vapor barrier. After parging the walls with a damp-proofing material, use construction adhesive to attach heavy (6-mil at a minimum) sheet polyethylene to the foundation walls. Then place sheets of rigid foam insulation over the plastic sheeting. Caulk and tape the foam seams to seal them. If the seams are airtight, the insulation layer becomes a second vapor barrier and makes condensation less likely because it isolates cool basement walls from warm air.

Option three: Exterior solutions. To waterproof exterior foundation walls, first excavate them. At that time, you should also upgrade the perimeter drains, as shown in "Foundation Drainage,” on p. 203. Then, after backfilling the excavation, slope the soil away from the house. That is, no waterproofing material will succeed if water stands against the foundation. Before applying waterproofing membranes, scrub the foundation walls clean and rinse them well.

► Liquid membranes are usually sprayed on, to a uniform thickness specified by the manufacturer, usually 40 mil. That takes training, so hire a manufacturer-certified installer. Liquid membranes are either solvent based or water based. Modified asphalt is one popular solvent-based membrane that contains rubberlike additives to make it more flexible and durable. Asphalt emulsions are water based and widely used because, unlike modified asphalt, they don’t smell strong, aren’t flammable, and won’t degrade rigid foam insulation panels placed along foundation walls. Synthetic – rubber and polymer-based membranes are also water based; they’re popular because their inherent elasticity allows them to stay flexible and span small cracks. Note: Water-based membranes dry more slowly than solvent-based ones and can wash off if rained on before they are cured and backfilled.

► Peel-and-stick membranes are typically sheet or roll materials of rubberized asphalt fused to polyethylene. They adhere best on preprimed walls. To install these membranes, peel off the release sheet and press the sticky side of the material to foundations. Roll the seams to make them adhere better. Peel-and-stick costs more and takes longer to install than sprayed – on membranes, but they’re thicker (60 mil, on average) and more durable. Though not widely used on residences, these materials seem justified on sites with chronic water problems. They’re often called Bituthene®, after a popular W. R. Grace Construction product.

► Air-gap membranes aren’t true membranes because they don’t conform to the surface of the foundation. Rather, they are

rigid plastic (polyethylene) sheets held out from the foundation by an array of tiny dimples, which creates an air-drainage gap. Water that gets behind the sheets condenses on the dimples and drips free, down to foundation drains. (For this system to work, you must coat the foundation walls first.) Air-gap sheets are attached with molding strips, clips, and nails; caulk the sheet seams.

► Until technology transformed waterproofing compounds, cementitious coatings rivaled unmodified asphalt as the most common stuff smeared onto foundations. These days, acrylic additives make cement-based coatings a bit more flexible, but they will still crack if the foundation flexes. Bentonite, a volcanic clay sheathed in cardboard panels, swells 10 times to 15 times its original volume when wet, keeping water away from foundation walls. Use construction adhesive or nails to attach the panels. These panels are costly and not widely available, and they can be ruined if rained on before the foundation is backfilled.

Leave a reply