EXAMPLES FROM THE DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS

A majority of the projects in the Joint Venture for Affordable Housing (JVAH) were developed under some version of Planned Unit Development zoning or subdivision regulations.

A majority of the projects in the Joint Venture for Affordable Housing (JVAH) were developed under some version of Planned Unit Development zoning or subdivision regulations.

Knoell Homes, developer of Cimarron, the’JVAH Project in Phoenix, saved at least six months by utilizing the PUD approach instead of applying for rezoning under the standard sub – _ division ordinances. This time saving reduced interest cost by approximately $106,000 or about $415 per unit. The cost reduction was passed on to the home buyers.

Rick Counts, former Phoenix Planning Director, expressed his frustration that PUDs require Home Owners Associations (HOAs). Many builders do not want to involve themselves with HOAs, and avoid using PUDs for that reason.

Hood Enterprises, developer of Innovare Park, applied for and was granted residential multi-family zoning for the site. The developer then applied for and was granted a supplemental PUD zoning permit. Under this permit, Hood Enterprises negotiated a site plan with city officials that allowed all singlefamily construction. The density – 12 units per acre – exceeded allowable maximums under standard single-family zoning for the area, but reduced the density that would have been allowed in multi-family development. The arrangement satisfied city officials, who stated that the PUD

approach "provides a higher degree of regulation but permits the developer more flexibility in principal and accessory uses and of lot sizes than conventional zoning."

approach "provides a higher degree of regulation but permits the developer more flexibility in principal and accessory uses and of lot sizes than conventional zoning."

In developing "The Park", an affordable housing demonstration in Lacey, Phillips Homes used a PRD authorization that allowed the developer to ‘ construct a mix of townhouses and detached units, and to make his own decisions regarding lot sizes. Phillips added 23 building lots to the 153 that were originally planned, bringing the total to 176.

The city of Birmingham rezoned Williamsburg Square, a project built by Malchus Construction Company, as a PRD, enabling Malchus to increase density from 40 to 111 units. The PRD designation also accelerated processing time from the normal 6 to 18 months to five months, saving $9,600 on the subdivision or $86 per unit, with the saving being passed on to the buyers.

Lincoln, Nebraska The City of Lincoln allowed Empire

Homes, Inc., to include its affordable housing project, "The Parkside Village," in an already-approved Community Unit Plan (CUP). This made it possible for the developer to increas’d the project’s density from 32 to 52 units.

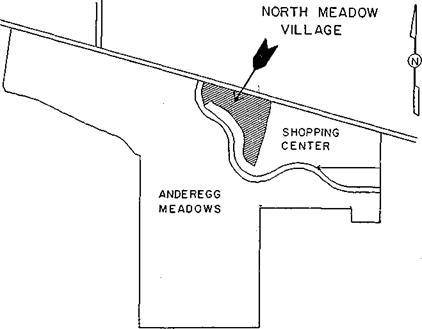

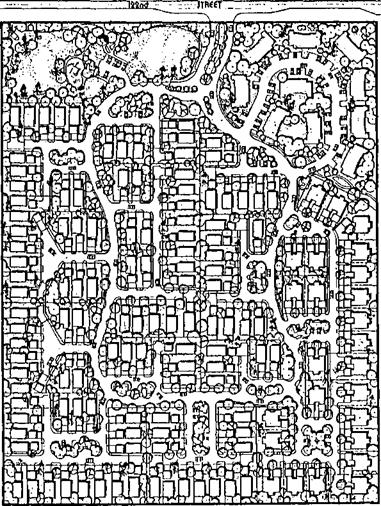

Black Bull Enterprises, Inc., developer of the affordable housing project "North Meadow Village," sought and secured from the city a number of innovative zoning modifications for the land parcel of which North Meadow Village forms one part. The parcel is situated in an area zoned for low-density, single-family construction at four units per acre. Black Bull requested establishment of a multifamily zone (22 units per acre) around a shopping center in the 150-acre tract located on a two-lane state highway, and a medium-density singlefamily strip (6.28 units per acre) separating the low-density singlefamily zone from the multi-family zone. In effect, he asked the Planning Bureau to trade higher densities in one portion of the tract for lower water and sewer usage in the commercial and retail area, with no net change in total water and sewer demand. The rezoning was approved by the city.

Black Bull Enterprises, Inc., developer of the affordable housing project "North Meadow Village," sought and secured from the city a number of innovative zoning modifications for the land parcel of which North Meadow Village forms one part. The parcel is situated in an area zoned for low-density, single-family construction at four units per acre. Black Bull requested establishment of a multifamily zone (22 units per acre) around a shopping center in the 150-acre tract located on a two-lane state highway, and a medium-density singlefamily strip (6.28 units per acre) separating the low-density singlefamily zone from the multi-family zone. In effect, he asked the Planning Bureau to trade higher densities in one portion of the tract for lower water and sewer usage in the commercial and retail area, with no net change in total water and sewer demand. The rezoning was approved by the city.

The city added PUD provision to its zoning regulations in 1980. Under this provision, Minchew Homes, developers and builders of "Forestwood II," were able to increase density from 2.9 to 5.8 units per acre.

Under this city’s PUD, Holland Land Company was able to cluster homes, increase open spaces, and mix singlefamily detached units, duplexes,, and quadplexes in "Woodland Hills," a subdivision of HUD-code manufactured homes.

Under this city’s PUD, Holland Land Company was able to cluster homes, increase open spaces, and mix singlefamily detached units, duplexes,, and quadplexes in "Woodland Hills," a subdivision of HUD-code manufactured homes.

|

|

|

|

|

Other JVAH demonstration projects developed and built under PUD-type ordinances include: Elkhart, Indiana; Knox County, Tennessee; and Charlotte, North Carolina.

Housing developments are built on borrowed money on which the developer makes interest payments each month. Developers also incur an overhead cost each month. The more quickly the homes can be built and sold, the more the interest and overhead costs can be reduced. According to a study by the Los Angeles County Land Development Center, every month of delay adds, by conservative estimate, 2 percent to the purchase price of a new home. These savings can be passed on to home buyers. Local jurisdictions can therefore make a direct contribution to affordable housing by expediting theirprocedures regulating land use and housing construction.

“Most builders don’t know the true cost of delay. Everyone assumes that it’s only interest, but the true cost includes overhead, material and labor inflation, and the lost opportunity to make a profit.”—John Phillips

Housing is governed at the local level by an array of codes, rules, and procedures which have typically grown up over a substantial period of time, and which often do not represent a coordinated system. A basic step that municipalities can take to promote affordable housing is to review the entire regulatory process from zoning through permitting as it is actually experienced by developers, to identify procedures that can be simplified, abbreviated, or improved.

“Concurrently with the Affordable Housing Demonstration project,” commented Jon Wendt, “Phoenix was pursuing an aggressive regulatory relief campaign under the leadership of Mayor Hance. Cimarron provided tangible evidence of the benefits to citizens of government deregulation. From the start, our primary interest in the project was to field tesj deregulation ideas to see if they worked, and, if they did, to incorporate them as permanent changes.”

Municipalities may wish to implement certain changes immediately. In other instances, changes that appear to be desirable can be used to expedite a specific affordable housing project as a test. The project can be evaluated, the changes modified if necessary, and support gained among agencies and officials who will have to implement them.

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Areas recommended by the National

League of Cities for review include

the following:

• Length of the process from application to approval or issuance of a permit. A builder/developer should know how much time it will take before a decision is made on his or her proposal. For example, there should be a fixed review period for subdivision plans, at the end of which, if no action has been taken, the plan will be automatically approved.

• Number of permits, approvals, hearings, and administrative reviews necessary for construction, and the additional number necessary for occupancy.

• Number of agencies, departments, boards, and other groups that must review an application.

о Types of information and amount of detail necessary for the kinds of approvals that are required.

Techniques that can be used in such a review study include:

• ![]() Review of city records to ascertain the number of applications received and approved, the agency or agencies involved, and the length of time involved.

Review of city records to ascertain the number of applications received and approved, the agency or agencies involved, and the length of time involved.

• Review of items in process during a specified current period, to learn how the system works in practice and where problems may exist.

The study should examine each of the three principal stages of the application process and make recommendations for improving procedures at each stage, as follows:

The study should examine each of the three principal stages of the application process and make recommendations for improving procedures at each stage, as follows:

1. The Pre-application Stage

In this stage, the developer should receive an overview of all that will be required during the regulatory process, including approvals needed, departments involved, and the best methods for moving through the system efficiently, and should be advised of the anticipated timeframe for approval.

2. The Staff Review Stage

Procedures can be reviewed for fast-tracking possibilities, ways to offer combiried or simultaneous reviews, mandatory deadlines, involvement of expediters or coordinators, elimination of duplication of review among Various agencies, concurrent reviews, and use of a management information system to track applications. Some local governments have developed a plan* review checklist to guide developers through the review procedures. If all steps on the

checklist are carefully followed, the review can be brief and relatively simple.

3. The Citizen Review Stage

Not all communities have ordinances that provide for citizen review procedures. Where such reviews are required, they target possible improvement in such areas as: convening of informal neighborhood meetings to disseminate information and respond to concerns prior to finalization of designs or the holding of public hearings; improvement of public hearing procedures through adoption of fair and consistent rules on who is heard, when, for how long, and how decisions are made; combining hearings when the approval of more than one governmental body is required; shifting some responsibilities from the planning commission to a hearing official, staff, or other party or entity; and adoption of mediation procedures in lieu of resorting to the courts to resolve difficult cases.

City staff responsible for inspection must respond to builder and developer requests in a timely and scheduled manner. Developers and builders have a responsibility to assure that the work for which inspection is requested has been completed and meets the relevant criteria. Cities are justified in requiring that their time and expertise are efficiently used.

City staff responsible for inspection must respond to builder and developer requests in a timely and scheduled manner. Developers and builders have a responsibility to assure that the work for which inspection is requested has been completed and meets the relevant criteria. Cities are justified in requiring that their time and expertise are efficiently used.

Permit and inspection fees should bear a reasonable relationship to the actual cost of performing the inspections and issuing the permits. It is inappropriate to use them as a form of indirect tax.

•*-y

Leave a reply