Meeting My Role Model on a Habitat Build

![]()

roof, cutting out rotten sheathing with a circular saw, reaching as far as I could, with my foot supported by Helen, whom I’d just met. Just as I was stretched to my limit, depending totally on her for support, Helen said, “You know, my friends say a 72-year-old woman doesn’t have any business being up on a roof.” I finished cutting out the rotten section of roof, but she had shaken my world: T thought she was 50.

Since then, Helen and I have become best friends. It has been nine years since we were up on that roof. We have traveled with Habitat to Africa, participated in several of Jimmy Carter’s Habitat projects, and worked hundreds of days together for our local affiliate. Helen continues to

work every Thursday in the field, moving at a steady, even pace. Her specialty is vinyl siding, though she can do it all.

Helen, who was a Navy Lieutenant in 1945 and was widowed nearly 25 years ago, is unflappable, taking everything in stride. Now 81 years young, her experience and attitude provide me with a wonderful perspective on life. Over the years, she’s become almost family, helping me build my two-story garage and spending time with my family (my children adore her), all the while quietly exuding a serenity I hope someday to attain myself. Role models are where you find them, but I found mine on a roof, working for Habitat.

-Anna G. Carter

[Photo ® Anna G. Carter.]

![]()

for installing a poly vapor barrier are provided in the next section.

Vapor barriers are often eliminated in warm climates, especially in areas of low humidity, such as the Southwest. But you may want to consider installing a vapor barrier beneath the exterior siding if the house will be exposed to warm, moist air outdoors and frequent air-conditioning indoors.

In mixed-climate zones—the region that extends from the mid-Atlantic states through the Carolinas and west by southwest to north

ern Texas—the need for a vapor barrier is minimal. In those regions, where mild winters are the rule, any moisture that does enter the wall cavities can dry from the outside in during the summer and from the inside out during the winter.

Installing a polyethylene vapor barrier

To work effectively, a vapor barrier must be installed with care. Even the smallest holes in a poly or kraft-paper vapor barrier must be

sealed with houscwrap tape or its equivalent. Use a durable, high-quality tape; neither duct tape nor packing tape will hold over the long run.

A friend of mine is a carpenter in Fairbanks, Alaska. They’re serious about vapor barriers up there. They cut sheets of poly from rolls that are 10 ft. to 20 ft. wide and 100 ft. long, covering the entire ceiling and all the exterior walls (on the inside). They even make sure to put poly behind a bathtub installed against an exterior wall.

In any given room, there are two steps to installing a poly vapor barrier. This isn’t a job you want to do solo; have helpers so that some can spread the sheet out over framing members while others staple it fast. You can begin as soon as all the insulation is in place.

1. Install the ceiling poly. Cut a piece of poly to fit the ceiling. If you have to use several pieces, make sure they overlap by at least one joist (or rafter, if you’re working on a cathedral ceiling). Seal overlaps with a layer of mastic, acoustical sealant, or housewrap tape. At the edges of the ceiling, the poly should lap at least 3 in. down onto the walls. Begin stapling the poly to the joists or joist chords in the center of the room and work out toward the walls. My friend staples about 12 in. o. c. through small, precut squares of heavy paper. This keeps the poly from tearing. Fit the poly tightly into all corners so the drywall will go on easily. The drywall holds the poly tight against the studs and insulation.

2, Install poly on the walls. Make this sheet continuous so that it laps over the ceiling poly along the wall’s top plate and extends past the bottom plate to lap about 3 in. onto the subfloor surface. First staple the sheet along the top plate, working from the upper center of the wall and down and out to the edges of the

wall. If you need to join one sheet of poly to another, overlap them by at least one stud and seal the lap as described previously.

You can sheet right over door and window openings, then cut openings in the poly after it’s completely stapled in place. If the windows and doors have already been installed, cut the poly along the inner edge of the jambs. If the windows and doors haven’t been installed yet, wrap the poly around the trimmers, headers, and sills. Avoid loose flaps that can catch the wind and cause tearing.

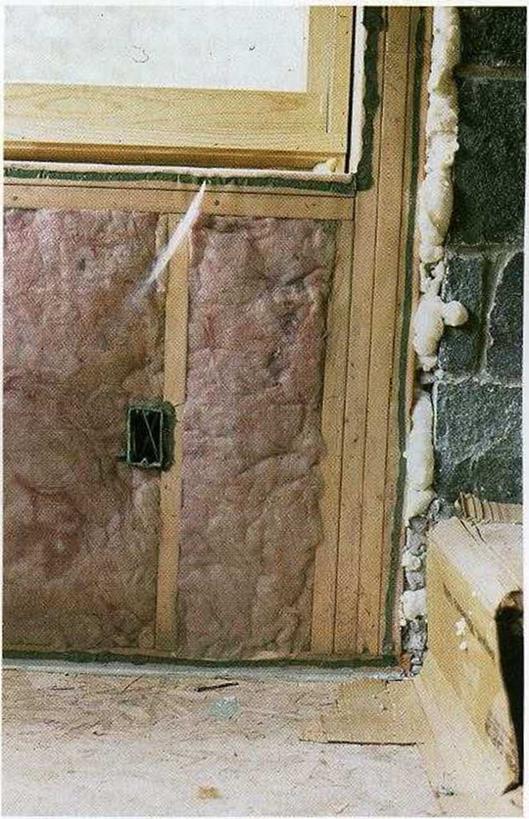

To prevent leakage at electrical outlets, use airtight boxes. Available at most electrical – supply stores, airtight boxes have a broad, flexible gasket around the front edge, where a poly barrier can be sealed easily. Alternatively, you can simply cut a box-size opening in the poly and seal the poly to the electrical box with a bead of caulk (see the photo below).

To prevent leakage at electrical outlets, use airtight boxes. Available at most electrical – supply stores, airtight boxes have a broad, flexible gasket around the front edge, where a poly barrier can be sealed easily. Alternatively, you can simply cut a box-size opening in the poly and seal the poly to the electrical box with a bead of caulk (see the photo below).

|

|

STEP 4 Provide Adequate Ventilation

STEP 4 Provide Adequate Ventilation

Now that we have a tight, well-insulated house, what do we do when we want a breath of fresh air? And how can we rid the house of kitchen odors and steam from cooking, showers, and the like? Indoor-air-quality problems are magnified in a new house because of fumes from new carpets, vinyl flooring adhesive, and paint. Obviously, you can open a couple of windows to get some fresh air, as long as the weather is cooperative. But what if you’re not comfortable opening windows in your neighborhood? That’s a problem. And what if it’s -15°F outside? What if its 105°F and humid? Opening windows when the weather is extreme or unpleasant undermines the effort you put into creating an energy – efficient house. There is a better solution, and it’s called mechanical ventilation.

All houses need at least a few small fans in critical locations where large volumes of vapor are created. A mechanical ventilation system can help maintain good indoor-air quality without making a lot of noise or costing a fortune. Unfortunately, my experience is that many local building codes (and building inspectors) have some catch-up work to do when it comes to understanding house ventilation. You’re better off finding a knowledgeable and reliable HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) contractor with up-to-date knowledge of home ventilation requirements. That said, proper ventilation for small, affordable houses isn’t all that difficult to obtain.

Source ventilation is the key to reducing moisture and odors

You can start by installing adequate spot, or source, ventilation wherever moisture or odors are created. Venting moist air directly

to the outside prevents it from escaping through the walls or ceilings, where it can cause damage. At a minimum, showers and stoves should have exhaust fans that are controlled by simple on-off switches or wired to come on automatically when a bathroom light is turned on or the stove is being used. For a stove installation, mechanical ventilation is usually provided by a vent hood equipped with a fan. In a bathroom, a variety of ceiling – mounted fans are available, including models with built-in lights.

Exhaust fans in moisture-producing areas should always be vented directly outdoors. That means out through a wall or up through the roof and not into an eave soffit or a crawl space. When we moved into our home in Oregon, I discovered that the clothes dryer was vented into the crawl space. Some pretty creepy looking stuff was growing down there in the dark. Even worse is venting moist kitchen or bathroom air into the attic.

Try to keep vent runs short—less than 10 ft., if possible. Avoid running vents through the attic, if possible; install them in interior soffits and dropped ceilings instead. If you can’t avoid running a vent through the attic,

then make sure it is well insulated. This is cru-

%

cial in cold climates, where heat inside the attic can cause ice damming along the eaves. This is serious business, so pay attention to the details.

Good indoor-air quality requires air exchange

We all need fresh air to stay healthy, and in a tightly built house, some form of mechanical air exchange is essential. You can provide air exchange fairly inexpensively by using a bathroom exhaust fan controlled by an automatic timer. Look for a fan that moves air at 80 CFM (cubic feet per minute) to 120 CFM. Set the timer to run the fan about two-thirds of the

|

|

|

|

Leave a reply