ROOF JACKS AND VENTS

Most skylights are manufactured with a complete flashing package and instructions for installation in a rough opening in the roof framing. Some are available with a kit to adapt the flashing to unusual roofing materials or pitches. Skylights are available in fixed or operable types with screens and/or sun-shade devices. Rough-opening sizes are specified and usually correspond with standard rafter spacing.

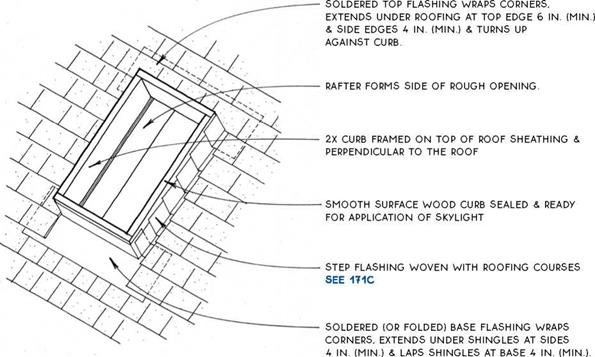

Many fixed skylights require a flashed curb to which the manufactured skylight is attached. With these skylights, the curb must be flashed like any other large penetration of the roofing surface, such as a dormer or a chimney (see 174 and 175C). Site-built curbless skylights are fixed and appear flush with the roof (see 176). Some codes prohibit these skylights because of the requirement for a curb.

For skylight framing, see 136A & B.

For Use with Manufactured Skylight

|

|

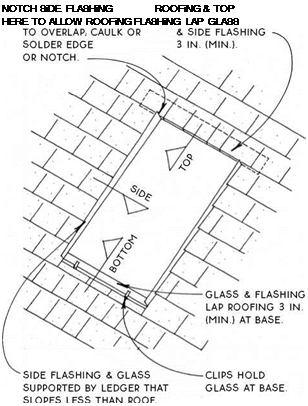

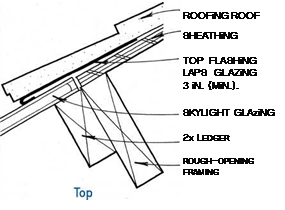

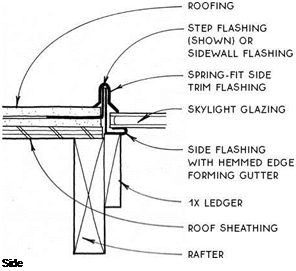

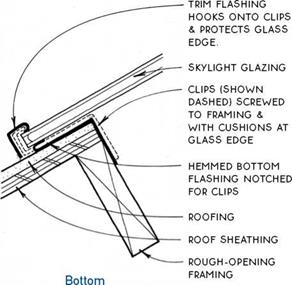

A site-built curbless skylight is woven in with the roofing. Its bottom edge laps the roofing, and its top edge is lapped by roofing. This means that the skylight itself must be at a slightly lower pitch than the roof. Ledgers at the sides of the rough opening provide the support at this lower pitch. If built properly, there is no need for any caulking of these skylights except at the notch at the top of the side flashing. Insulated glass should limit condensation on the glazing, but any condensation that does form can weep out through the clip notches in the bottom flashing. In extremely cold climates, the side flashing should be thermally isolated from the other flashing to prevent condensation on the flashing itself.

Curbless skylights are especially practical at the eave edge of a roof, where the lower edge of the skylight does not have to lap the roofing. This condition, often found in attached greenhouses, will simplify the details on this page because the slope of the skylight can be the same as the roof. The top and side details above right are suitable in such a case. Codes that require curbs preclude the use of these skylights.

Curbless skylights are especially practical at the eave edge of a roof, where the lower edge of the skylight does not have to lap the roofing. This condition, often found in attached greenhouses, will simplify the details on this page because the slope of the skylight can be the same as the roof. The top and side details above right are suitable in such a case. Codes that require curbs preclude the use of these skylights.

With the exception of wood roofs, which are now made with lower-grade material than in the past, today’s roofing materials will last longer than ever before, and can be installed with less labor. Composite materials now take the place of most natural roofing materials, including wood shingle and slate.

The selection of a roofing material must be carefully coordinated with the design and construction of the roof itself. Some factors to consider are the type of roof sheathing (see 162-166), insulation (see 197-205), and flashing (see 167-176). For example, some roofing materials perform best on open sheathing, but others require solid sheathing. Some roofing materials may be applied over rigid insulation; others may not.

Many roofing materials require a waterproof under – layment to be installed over solid sheathing before roofing is applied. Underlayment, usually 15-lb. felt, which can be applied quickly, is often used to keep the building dry until the permanent roofing is applied.

In the case of wood shakes, the underlayment layer is woven in with the roofing courses and is called interlay – ment (see 186).

Other considerations for selecting a roofing material include cost, durability, fire resistance, local climatic conditions, and the slope (pitch) of the roof.

Cost—Considering both labor and materials, the least expensive roofing is roll roofing (see 180-181). Next in the order of expense are asphalt shingles (see 182-183), followed by preformed metal (see 190), wood shingles (see 184-185), shakes (see 186-187A), and tile (see 187B-189). Extremely expensive roofs such as slate and standing-seam metal are not discussed in depth in this book.

Durability—As would be expected, the materials that cost the most also last the longest. Concrete-tile roofs typically have a 50-year warranty. Shake and shingle roofs can last as long under proper conditions but are never put under warranty. Preformed metal and asphalt shingles are usually under a warranty in the 15-year to 30-year range.

Fire resistance—Tile and metal are the most resistant to fire, but fiberglass-based asphalt shingles and roll roofing can also be rated in the highest class for fire resistance. Wood shakes and shingles can be chemically treated to resist fire, but are not as resistant as other types of roofing.

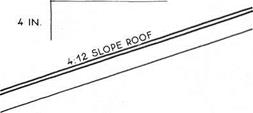

Slope—The slope of a roof is measured as a proportion of rise to run of the roof. A 4-in-12 roof slope, for example, rises 4 in. for every 12 in. of run.

There are wide variations among roofing manufacturers, but in general, the slope of a roof can be matched to the type of roofing. Flat roofs (У8-т-12 to!/4-in-12) are roofed with a built-up coating or with a single ply membrane (see 178-179). Shallow – slope roofs (1-in-12 to 4-in-12) are often roofed with roll roofing. Special measures may be taken to allow asphalt shingles on a 2-in-12 slope and wood shingles or shakes on a 3-in-12 slope, and some metal roofs may be applied to 1-in-12 slopes. Normal-slope roofs (4-in – 12 to 12-in-12) are the slopes required for most roofing materials. Some materials such as built-up roofing are designed for lower slopes and may not be applied to normal slopes.

|

|

|

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leave a reply