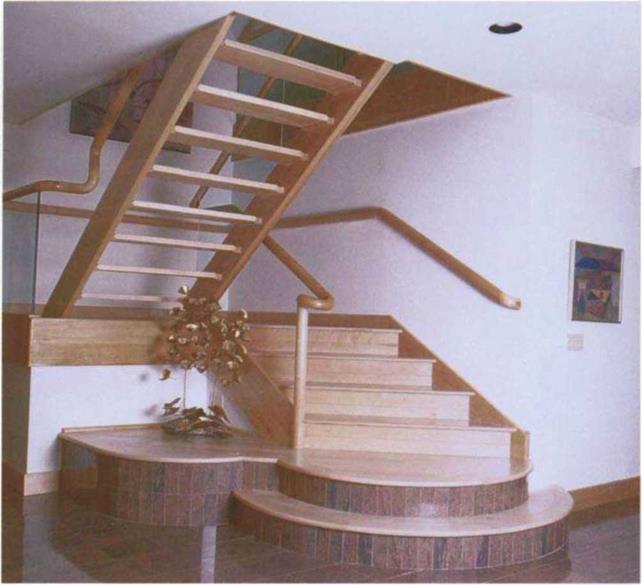

STRAIGHT-FLIGHT STAIRS

Stairs and the stringers that support them come in different shapes and styles. Some stringers have a simple plumb cut at the top and a level cut at the bottom, with fixed cleats in between to hold the treads. Most stringers have notches cut in them where treads and risers are attached. Stringers that sit between walls and are hidden from view are called closed stringers. When they are exposed—and usually finished—they are called open stringers.

Like the gable roof discussed in Chapter 6, the straight-flight stairs covered in this chapter are basic and simple. At the same time, the skills necessary to build

them are common to all stairs, no matter how complex they may seem. Once you know how to build a set of straight-flight stairs, you have the basic rise-run information you need to build other types.

The first concern of stairbuilding is the stairwell (see the drawing on p. 157). Because they have to be wide enough for the stair structure and long enough for adequate headroom, stairwells take up a considerable amount of square footage. Most of us know what it’s like to go up a narrow set of stairs, especially one with inadequate lighting. It’s worse yet when you have to duck your head to

|

miss hitting the front edge of a stairwell. So for comfort and safety, codes require most stairs to be at least 3 ft. wide and have at least б ft. 8 in. of headroom along the total length of the stair.

When I can, I like to make stairs even wider than 3 ft., because more than people (like pianos and furniture) will be moved up and down. The average straight-flight stair will fit easily into a stairwell that is a minimum of 371/г in. wide and about 130 in. long. (To frame this opening, see Chapter 5.)

Seemingly minor details can have an impact on stairs. I’ve built stairs that fit between walls that were sheathed with Унп. plywood, covered by VHn. drywall, and had а 3/нп. skirtboard (stair trim) along each stringer. This meant that the rough opening had to be 391Л in. wide instead of 37V2 in. Also, I like to leave an extra У2 in. so that all the stair parts fit easily in place. If you don’t notice these details until the framing is complete and it’s time to build stairs, you’ll have to redo a lot of work to make it right.

Carpenters laying out the house frame also need to leave adequate room for landings. Because it’s dangerous to open a door and immediately face a step down, building codes require a landing at the top and bottom. Many stairs have landings midflight, where you can stop to rest or make a turn and proceed in another direction. Landings have to be at least the same width and depth as the stairs, which means 36-in.-wide stairs require a landing that is at least 36 in. by 36 in. square. When snapping lines on the floors, building walls and laying out stairwells, remember that these clearances are finish requirements, so account for finish wall thicknesses (typically Уг-іп. drywall) on each side. This way you don’t wind up with a landing that is 35 in. by 35 in. and not up to code.

Landings in the middle of stairs play no part in determining the total rise. They’re figured as if they were large treads. They do make the total run longer, so if a landing falls midflight, seven risers up, for example, its height above the floor will be seven times the height of a riser. If the riser height is 7-in., the landing should be built at 49 in.

Leave a reply