The technologies of the medieval revival

The conquest of the waterways: inland water transport and mills

The great technological phenomenon of the Middle Ages is the development of mills, perhaps a natural companion of the revival of interest in watercourses. Since the road network was in bad shape and the countryside was not safe, the development of commerce in the 10th century first relies on the watercourses. Demographic expansion and the nearly exclusive use of cereals to feed the population drive major development of the flour trade. In this period the consumption of bread made from flour develops while consumption of porridge decreases. It was quite natural to build mills along watercourses that were already indispensable for water supply and transport, a heritage from the Roman era. The development of mills is nothing less than extraordinary in all the regions of France, England, and Holland. On the Roussillon canal, mills are already numerous at the end of the 9th century, and 10th century mills with multiple wheels can be found on there.[465]

Twenty years after the Battle of Hastings, in 1086, William the Conqueror put together an inventory of the possessions of his English domains in the “Domesday Book”. No less than 5,624 water mills are listed here (but no windmills and only one

|

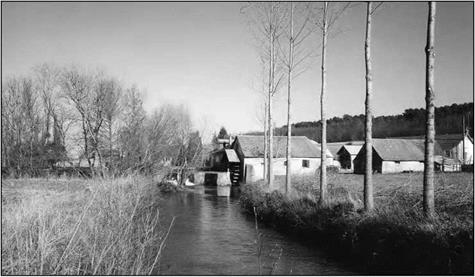

Figure 9.2 A tanning mill (to crush bark for its use in a tannery) on a small river, near Luche- Pringe, in the Sarthe department of France (photo by the author) |

tidal mill). This amounts to about one mill for every fifty houses, whereas there had only been a total of about a hundred mills a century earlier. At this period all these mills were for grinding wheat. In other regions, such as Picardy, the use of mills grows rapidly – but one must not take all of the data at face value.[466] Boat-mounted mills can also be found under the Grand Pont of Paris.

In the 10th century mills are for the most part the property of lay lords or bishops. This is the “banal” mill, to which vassals, or feudal subjects, are required to bring their grain to be ground and pay an unpopular tax (the “ban”). But the use of hydraulic energy goes beyond the grinding of cereals. Industrial uses appear very early on as in Andalusia.[467] The fuller’s mill uses a system of cams to beat cloth; it appears in Italy in the 10th century, and in Burgundy (France) in the 12th century. About the same time the use of hydraulic energy to power forgehammers appears using the same principle. The first hydraulic sawmill in the Christian West appears to have been in Normandy (France) in 1204, and further evidence is found here and there in later years. Hydraulic energy has many other such uses: powering bellows for hammer forges, twisting fibers in yarn works, mixing beer, etc.

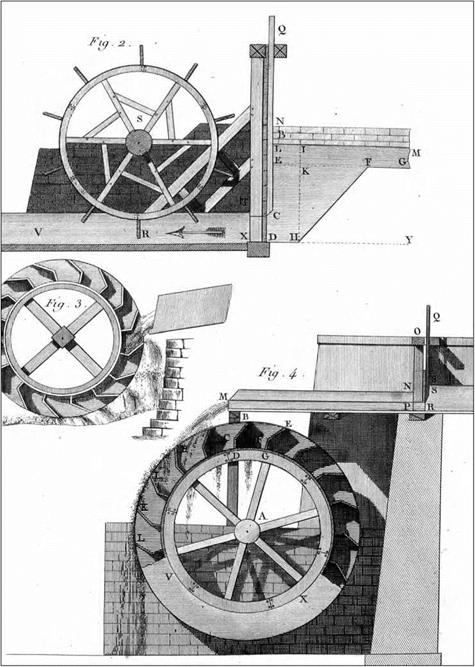

Horizontal-wheel mills are found in regions under Andalusian influence, for example along the Garonne River in France. Elsewhere the mills are almost always of vertical-wheel design. In the 10th century they are “undershot”, driven from below like the Roman mill described by Vitruvius (Figure 6.21). The overshot wheel is driven from above and can provide more power; it appears in the 11th century in mountain monasteries, where it is relatively easy to direct falling water to the device.[468]

The cities that begin to develop in the second half of the 11th century in western Europe establish widespread hydrographic networks, branching out from urban centers on the watercourses. Diverse water-dependent activities such as the flour, tanning, and cloth trades[469] develop along these watercourses. Populations are not very dense, and the running water contributes to the healthy environment of these newly emerging cities.

Ownership of the water mills progressively passes to the large abbeys from the 12th century on – the abbeys clearly wanted to take over both the lands and their associated water resources. Further on we describe an example regarding the very rich abbey of Citeaux in Burgundy (Figure 9.11). These ambitions of the abbeys obviously can lead to conflicts, especially when the flatness of the river slope limits the number of mills that can be supported on a given watercourse.

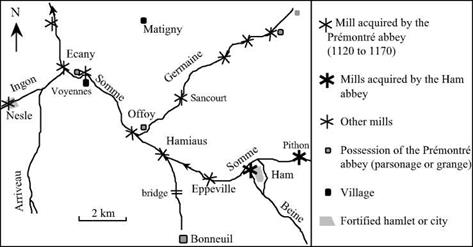

On the Somme river, examination of monastic archives reveals that to the west of Ham there was quite a concentration of mills (Figure 9.4) – no less than eight along some ten kilometers, and most of these mills had more than one wheel. In 1160 the monks of Bonneuil, the important parsonage of Premontre responsible for managing the abbey’s resources in this region, raised the height of the dam of the Eppeville mill (acquired before 1138) to increase its capacity. In so doing, they affected the operation of other mills in Ham, a city located several kilometers further upstream. The trial that followed lasted no less than four years, from 1167 to 1171, and involved jurists as well as lay and religious experts. The case was eventually heard in the court of Pope Alexander III. In the end the monks of Premontre were required to demolish their structure.

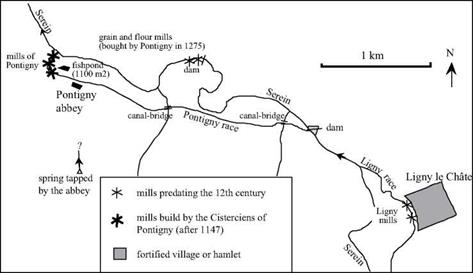

We can see that the development of mills necessarily included the transformation of natural rivers into managed watercourses, including overflow weirs to generate the head necessary to power the mills. The mills were sometimes co-located with the dam itself, or sometimes were placed on derivation canals, or races, issuing from the pool upstream of the dam. These races could attain lengths of several kilometers (Figure 9.5). During low-flow periods these installations kept the water level relatively high, thus favoring

|

Figure 9.3 Different types of vertical-wheel mills, traditional in France (Belidor, 1737 – ancient archives of ENPC): – above, an undershot wheel, from a river dam (like the mills of Figures 9.1 and 9.2); – below, an overshot wheel, for mountain creeks of low discharge (like the Roman mill of Barbegal, Figures 6.23 and 6.24); – in the middle, an intermediate configuration. |

|

Figure 9.4 The mills on the Somme River (France) west of Ham, in the 12th century. These mills likely existed since the 10th or 11th centuries, and were progressively acquired by the large abbeys like that of Premontre. From Dietrich Lohrmann (1996). |

the development of inland water transport.

The earliest navigation canals may have been in the 11th century, but it is not until the 15th century that locks appear in the West. Prior to this, barges had to be hauled up and down ramps. This inconvenience, along with the improvement of the road network, rapidly reduced inland water transport to a rather modest role in the overall interior commercial activity in Europe. Ferryboats are put into service for river crossings, and where the overbank area (submerged during floods) is much wider than the main channel (in which year-round navigation is possible), transverse levees must be built on the overbank to bring the road to the ferry landing and thus make it possible to cross the river in all seasons[470]. Apparently these transverse levees are of little consequence to the flow of water during floods. They cause the upstream water-surface elevation to be higher, but they attenuate the severity of the flood downstream creating a kind of intermediate storage area.

Up until this time mills had only been built on small or modest rivers. But from the start of the 12th century, the know-how for such installations on large rivers began to cross the Pyrenees. At Toulouse a 400-m long dam was built on the Garonne River. This dam was set at an angle to the river to increase the effective overflow length, a technique that we saw earlier on Andalusian dams. The dam was built of two rows of wooden piles anchored in the riverbed, with rock fill dumped between the two rows to form the structure. Along with two other smaller dams, this installation provided the necessary head to power a total of 45 mills, probably a record for this period (the reader may recall the dams built by the Arabs in the Fars, also designed to provide water for a number of mills

|

Figure 9.5 Location of mills on the Serein, a tributary of the Yonne, near the abbey of Pontingy in Burgundy (France). The installations at Ligny (dams and race) predate the 12th century. The dam (Figure 9.6), the race and the mills of Pontigny were built after the installation of the Cistercians (1147). Today the three mills of Pontigny have upstream-to-downstream drops of 1.5, 2.6, and 1.3 meters. Numerous conflicts arose between Pontigny and other water users, notably Ligny upstream, and the ancient abbey of Sant-Germain d’Auxerre that had properties downstream on the Serein. From Rouillard (1996) and Kinder 1996). |

– Figure 7.4).[471] This dam, whose height is unknown, is mentioned in a text from 1177. To our knowledge, there are no other large structures like this built prior to the 15th century.

Leave a reply