The future of the discoveries of the 3rd century BC

As we have shown, Lagide Egypt undergoes a period of troubles and reduced prosperity from the 2nd century, a situation not at all propitious for development. Ptolemy VIII (called Physcon – i. e. the vain) hunts down the Alexandrian intellectuals in 145 BC and later sends his mercenaries to attack this city that had revolted. Far from being lost, the discoveries of the 3rd century BC reappear in the hydraulic projects that we are going to describe subsequently. They comprise a patrimony shared by the Roman engineers and the scientists of the school of Alexandria from the first centuries of our era – the school poised for another fruitful period under Roman domination.

Even though Pergamon and Alexandria dominated intellectual life, the thread of innovation runs throughout the entire Hellenistic world in this period, from Egypt to the Black Sea. The first examples that we will describe are linked to the intensive urbanization that developed in Asia Minor. These are new cities in a mountainous country, and they demand new principles of water supply.

Hellenistic water delivery and the generalization of the siphon

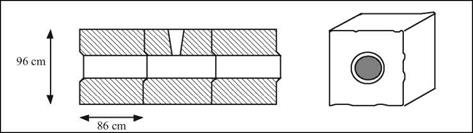

As we have seen in Chapter 4, the Greek aqueducts most often use clay pipes that follow the slope of the terrain, as would a free-surface canal. During the Hellenistic period, in the new cities of Asia Minor and Palestine, the technology of inverse siphons is developed to permit an aqueduct to cross a valley and return to a higher elevation. These siphons are schematically in the form of a “U” with depth of from 15 to 75 m (i. e. from the top to the bottom of the “U”.) The portion of the conduit that is under pressure (a “forced main”) is most often constructed from massive stone. Numerous pipe sections of this type have been recovered, often of cubical external shape, and fitted with ferrules so that individual elements can be connected to form a conduit (Figure 5.7). Often the upper portions of these elements have holes in them, probably serving as air vents, cleaning holes, or perhaps pressure-surge relief valves.

|

Figure 5.7 Example of a forced main in stone (Laodicee) (after Hodge, 1995) |

Inverse-siphon technology made it possible for Hellenistic water-delivery systems to cross valleys without the engineering structures (bridge-aqueducts) that the Romans later used for such crossings. Their development coincides with an improved knowledge of the effects of fluid pressure, as we have seen in the previous section. But it is difficult to say if this knowledge resulted from the technological development, or vice-versa. Table 5.1 summarizes some of the Hellenistic inverse siphons.

|

Table 5.1. Inverse siphons of Hellenistic technology (Hodge, 1995)

|

Leave a reply