The qanats in Egypt under the Achaemenid Empire

In Chapter 2 we described the invention of the qanat in Urartu and its development in Persia. After the conquest of Egypt by Cambyse, qanats are introduced in Egypt to irrigate the oases as well as the mountainous zones situated along communication routes (the wadi Hammamat, between Thebes and the ports of the Red Sea). Traces of three qanats constructed by order of Darius I (about 500 BC) have been found in the oasis of Kharga, some 300 km to the northwest of Asswan.[127] These qanats are as deep as 75 m, with a gallery several kilometers long and a rather flat slope compared to the usual practice, only about 0.5 per thousand.

Irrigation in the land of the Queen of Sheba Irrigated oases at the threshold of the desert

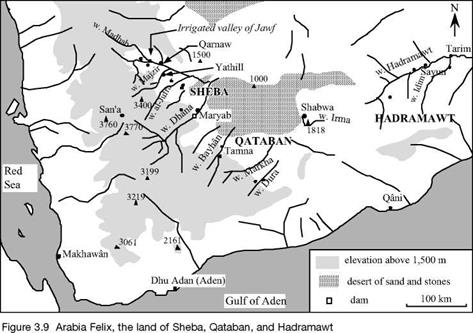

To the south of the Arabian peninsula, the mountains of Yemen rise to 3,000 m and capture the seasonal monsoon rains. The high valleys are therefore well watered – but the most prosperous regions are not found here. The shrubs from which incense and myrrh can be harvested are located, rather, on the edges of the arid interior desert, at about 1,200 m of altitude, in the lands of Qataban and Hadramawt. These aromatic resins become quite the fashion in all the countries of the East, in Greece, and eventually in Rome, from the 8th century BC. The richness of this land, soon to be called Arabia Felix,[128] is built on incense and myrrh – their harvest, exchange, and associated control of the caravan routes that lead to the north of Arabia along the eastern edge of the great mountains.

However it is only through hard work that the kingdoms of Sheba, Qataban,

|

|

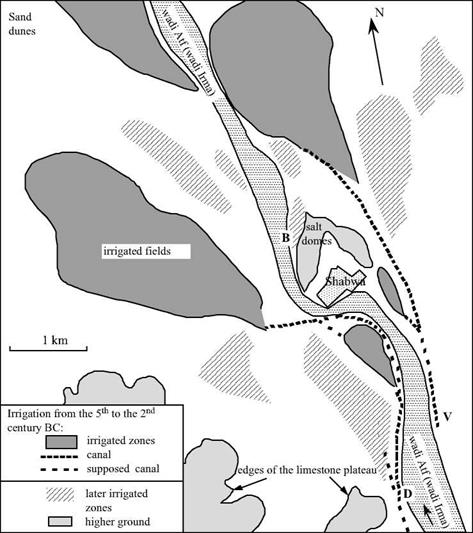

Hadramawt, and Ma’in, whose capitals are Maryab (today Ma’arib), Tamna (Hajar Kulhan), Shabwa, Yathill (Baraqish), find prosperity. Nothing is possible without water, without crops. The land between the mountains and the desert is very arid; the only sources of water are the wadis. These are normally dry, but are subject to violent floods when heavy rains fall on the high mountains from which they issue, two or three times a year between March and August. People had learned how to make use of this water resource long before incense came into fashion – very likely from the IIIrd millennium BC along the wadis of Dura, Dhana and Markha; and from the IInd millennium BC in the basin of the wadi Hadramawt (along the wadi Irma upstream of Shabwa, in particular).[129]

The water engineering techniques remained about the same through the era of prosperity of Arabia Felix. Deflector walls, weirs and small dikes, and occasionally true dams, constructed in the beds of the wadis, direct some of the silt-laden floodwaters toward a system of branching earthen canals. These canals are provided with outtakes – stones with grooves into which beams could be slid to control the water flow. Since the canals have a much gentler slope than the wadi, the currents are slower and therefore only the finest of the sediments are diverted to the crops with the water. The fields are quadrilateral in shape and surrounded by earthen levees, the whole comprising a vast irrigated zone. Gates permit controlled flooding of the fields to a depth of several tens of centimeters. Thus two resources are being used simultaneously: the water itself, making it possible to plant as soon as the field flooding is over; and the sediments, whose

|

|

|

ty meters at Maryab. This accumulation of soil requires that the canal system be reworked periodically, the intakes being raised or moved further upstream so that the water can still reach the fields.

|

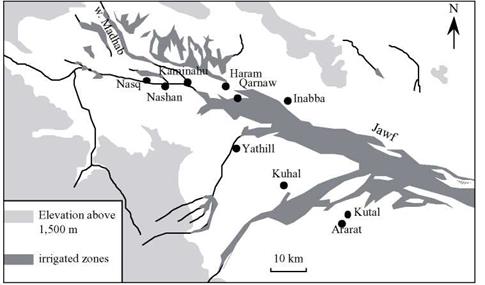

Figure 3.11. The irrigated valley of Jawf, and the city of the land of Sheba (Maryab is a little further to the south) – adapted from Robin (1991). |

This mastery of complex hydraulic systems could not be achieved without a strong social organization. The kingdoms mentioned earlier are effectively organized and hierarchical. They are dominated by Sheba from the beginning of the 7th to the 1st century BC, under the hand of the great Sheban sovereign Karib’Il Watar, the “Karibilu king of Sheba” mentioned in texts of the Assyrian Sennacherib. The sudarabic writing is original, using an alphabet related to the Phoenician. Numerous inscriptions still exist, commemorating for example the redistribution of irrigation water following the destruction by Karib’Il Watar of the city of Nashan, at the convergence of the wadis Madhab and Jawf (Figure 3.11):

“(Karib’Il Watar) took the rights of the king of Nashan and of Nashan to the waters of Madhab (…), took the water of dhu-Qafan at Sumhuyafa and at Nashan and granted it to Yadhmurmalik, king of Haram, took from Sumhuyaga and at Nashan the canals dhat – Malikwaqih and granted them to Nabat’ali, king of Kaminahu, and at Kaminahu the waters of the canals dhat-Malikwaqih (that are) beyond the boundaries of Karib’Il, built the enclosure of Nasq and peopled it with Shebans.. ..”45

Another later text attests to the concession of irrigated land to a dignitary of the city of Haram (located several kilometers from Qarnaw):

“Wahab’il son of Ammidhara, of the clan of Thabaran (…), chief of the horse-mounted troops of Haram, honored Matabnatiyan, god of Thabaran, (…), when he dug, bore, and lined with stone his well, and that Yashhurmalik Nabat granted him a flooded public (?) land, of which he took possession, extending from the enclosure of Dhu-Arnab upstream to his property, and the concession that is upstream, between the canal of Dhat Batalan and the road of Ma’in, and he acquired and brought into cultivation a number of 300 (parcels).”[130]

Numerous texts also describe the construction of hydraulic works. The following extract, despite its gaps, describes the construction of a canal and dike, again in the region of Haram:

“(the person in question) bound and dug Yasim (?) with the upper canal of the plain of the city of Haram, next to (?) this canal and the tour, (…) and the land that is subject (?) to the king of Sheba (.) he granted his inscription and his dike.”[131] [132]

There are regulations to protect the waterways against thoughtless incursions. One of the earliest known is from the 5th century BC, after a certain Karib’Il Bayyin had built a runoff channel around the small city of Nasq (in Jawf, populated by Sheban colonists after the destruction of Nashan, as is referenced in one of the extracts cited above). His son is then led to issue a decree:

“Damar Alay Watar, son of Karib’Il, has decided and decreed, for Sheba and its colonists, the clearing of the water collector wall (deflector?) of the city of Nasq, that his father Karib’Il had opened according to the inscription of easement where his father delineated it in writing.

Neither watered nor arid land shall be developed therein, and no irrigated produce or crop

48

shall be harvested therefrom.”

Neither the regularity nor the amplitude of the beneficial floods is guaranteed, as is clear from the following text. Thus, if two clans have neglected the practice of a ritual hunt dedicated to the god Halfan, and there is a water shortage two times in a row, the clans must carve an inscription to do penance for their sin in the hopes that Halfan will again irrigate their lands:

“The clan Anir and the clan Athar have confessed and done penance to Halfan (the principal god of Haram after the 2nd century BC) because they did not render unto him the ceremonial (?) hunt in the month of dhu-Mawsab when they took refuge at Yathill during the war of Hadramawt, whereas they made the pilgrimage of dhu-Samawi at Yathill and put off the ceremonial hunt until the month of dhu-Anthar. Therefore he (the god Halfan) did not grant them water for their irrigation network from the spring to autumn, because of an extremely low quantity of water, and they will be careful not to do the same thing again.”[133]

Thanks to these irrigation systems, artificial oases flourish along the wadis Dhana (we will come back to it later) and Markha, in Hadramawt (see also Shabwa on Figure 3.10). Although these regions have the oldest irrigation infrastructure, other systems are found on the wadi Bayhan in Qataban, where a 45-km continuous ribbon of land is irrigated and cultivated. Arabia Felix has some thirty cities between the 7th and 1st centuries BC, in the grand valley of Jawf and near the wadis Dhana, Ragwan, Juba, Harib, Markha, and Hadramawt. Most of these fortified cities have surface areas of from six to ten hectares; but they have neither sewers nor water supply infrastructure.

In the 1st century BC, merchants of Alexandria discover how to make an annual maritime voyage toward India, using the monsoon. This is a negative development for the economy of Arabia Felix, which thus loses its monopoly on the supply of spices. This century thus marks the beginning of a slow economic recession. Upland tribes (the Himyarites) begin their progressive domination beginning in the 1st century AD.

Leave a reply