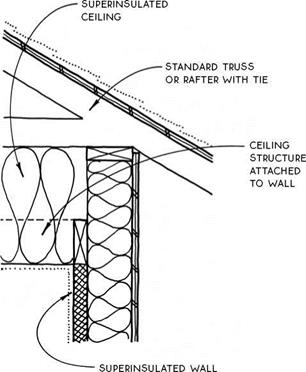

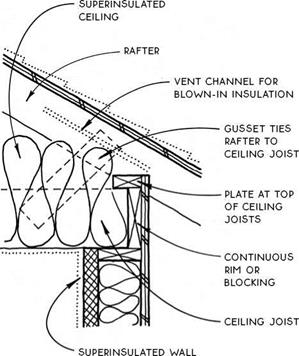

SUPERINSULATED CEILINGS

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

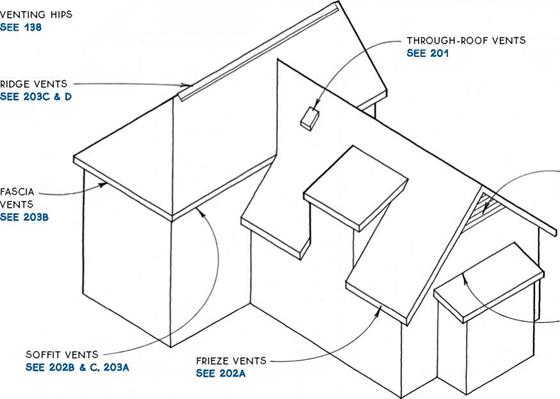

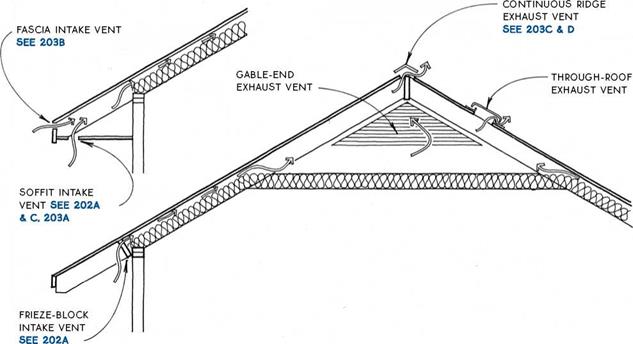

Roofs and attics must be vented to prevent heat buildup in summer and to help minimize condensation in winter. (Condensation is reduced primarily by the installation of a vapor barrier, see 197.) In addition, winter ventilation is necessary in cold climates to prevent escaping heat from melting snow that can refreeze and cause structural or moisture damage.

The best way to ventilate a roof or attic is with both low (intake) and high (exhaust) vents, which together create convection currents. Codes recognize this by allowing the ventilation area to be cut in half if vents are placed both high and low. Most codes allow the net free-ventilating area to be reduced from Уібо to У300 of the area vented if half of the vents are 3 ft. above the eave line, with the other half located at the eave line.

Passive ventilation using convection will suffice for almost every winter venting need, but active ventilation is preferred in some areas for the warm season. Electric-powered fan ventilators improve summer cooling by moving more air through the attic space

to remove the heat that has entered the attic space through the roof. The use of fans should be carefully coordinated with the intake and exhaust venting discussed in this section so that the flow of air through the attic is maximized.

Some roofing materials (e. g., shakes, shingles, and tile) are self-venting if applied over open sheathing. These roof assemblies can provide significant ventilation directly through voids in the roof itself. Check with local building officials to verify the acceptance of this type of ventilation.

A special roof, called a cold roof (see 204A), is designed to ventilate vaulted ceilings in extremely cold climates. The cold roof prevents the formation of ice dams—formed when snow thawed by escaping heat refreezes at the eave. When an ice dam forms, thawed snow can pond behind it and eventually find its way into the structure. The cold roof prevents ice dams by using ventilation to isolate the snow from the heated space.

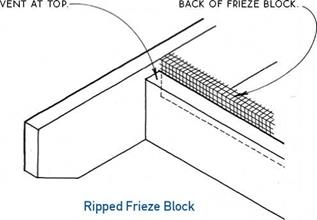

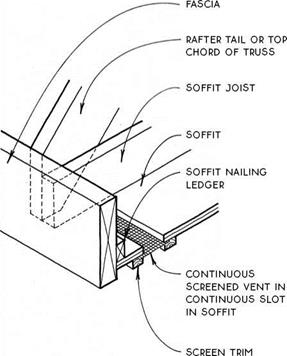

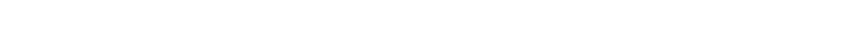

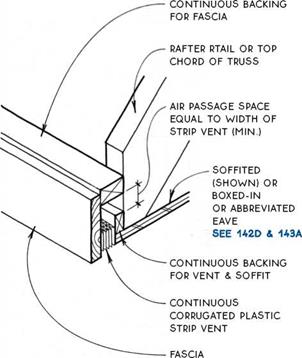

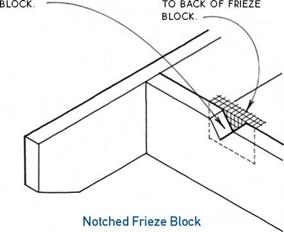

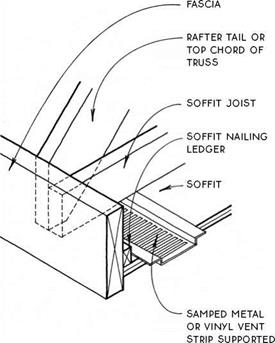

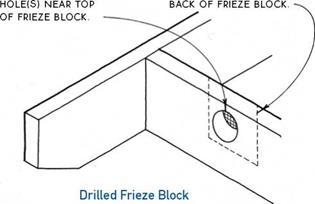

Intake vents—Intake vents are commonly located either in a frieze block or in a soffit or fascia. They are usually screened to keep out birds and insects. The screening itself impedes the flow of air, so the vent area should be increased to allow for the screen (by a factor of 1.25 for V8-in. mesh screen, 2.0 for //L6-in. screen). The net venting area of all intake vents together should equal about half of the total area of vents.

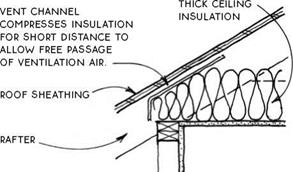

Vent channels may be applied to the underside of the roof sheathing in locations where the free flow of air from intake vents may be restricted by insulation. The vent channels provide an air space by holding the insulation away from the sheathing. These channels should be used only for short distances, such as at the edge of an insulated ceiling. For alternative solutions to this problem, see 198 & 199.

|

|

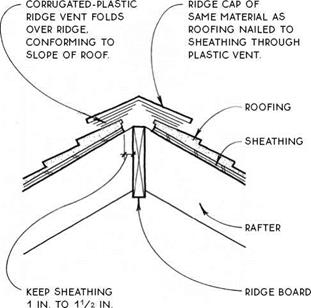

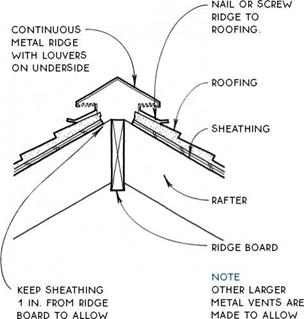

Exhaust vents—If appropriately sized and balanced with intake vents, exhaust vents should remove excess moisture in winter. There are three types of exhaust vents: the continuous ridge vent, the gable-end vent, and the through-roof exhaust vent.

The continuous ridge vent is best for preventing summer heat buildup because it is located highest on the roof and theoretically draws ventilation air evenly across the entire underside of the roof surface. Ridge vents can be awkward looking, but they can also be fairly unobtrusive if detailed carefully (see 203C &

D). (Another type of ridge vent, the cupola, is also an effective ventilator, but is difficult to waterproof against wind-driven rain.)

The gable-end vent is a reasonably economical exhaust vent. Gable-end vents should be located across the attic space from one another. They are readily available in metal, vinyl, or wood, and in round, rectangular or triangular shapes. Because the shape of gable-end vents can be visually dominant, they may be emphasized as a design feature of the building.

The through-roof exhaust vent is available as the “cake pan" type illustrated above or the larger rotating turbine type, available in many sizes. Through-roof vents are usually shingled into the roof and are useful for areas difficult to vent with a continuous ridge vent or a gable-end vent.

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

Corrugated Strip

Starter

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

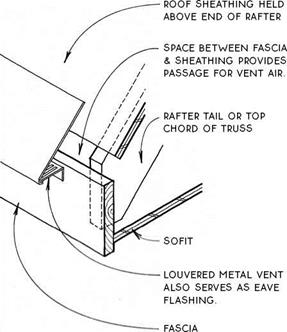

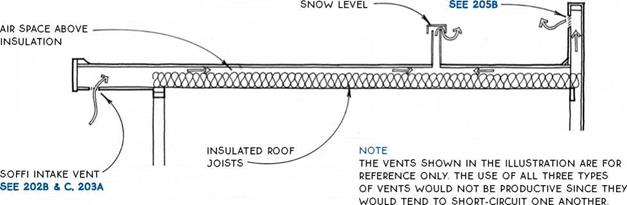

The cold roof is a way to protect vaulted ceilings in cold climates from the formation of ice dams. A cold roof is a double-layer roof with the upper layer vented and the lower layer insulated. The vented layer promotes continuous unrestricted air flow from eave to ridge across the entire area of the roof. This flow of cold air removes any heat that escapes through the insulated layer below. The entire outer roof surface is thus maintained at the temperature of the ambient air, thereby preventing the freeze-thaw cycle caused by heat escaping through the insulation of conventional roofs.

The typical cold roof is built with sleepers aligned over rafters and with continuous eave vents and complementary ridge or gable vents. A 3f/2-in. air space has been found to provide adequate ventilation, but a іУг-т. air space does not. The sleepers must be held away from obstructions such as skylights, vents, hips, and valleys to allow air to flow continuously around them.

A modified cold roof with extra-deep rafters to provide deeper than normal ventilation space but without the double-layer ventilation system can also work.

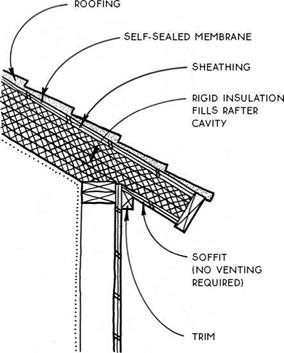

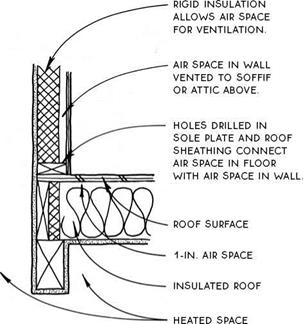

The warm roof also protects vaulted ceilings in cold climates from the formation of ice dams. Instead of isolating the snow from the insulation like a cold roof however, the warm roof prevents escaping heat from melting the snow by increasing insulation thickness. When the ceiling R-value is sufficient (approximately R-50 is recommended), the temperature on the surface of the roof can be maintained at the temperature of the snow. The snow will therefore not melt while the ambient temperature remains below freezing.

By using rigid insulation, the warm roof eliminates the ventilation space because there are no voids within which condensation can form, so there is no need to ventilate between the insulation and the roof surface. With snow effectively adjacent to the insulation, the insulative value of the snow itself will contribute to the insulation of the building. In this respect, the warm roof is superior to the cold roof because the cold roof exposes the outer surface of the insulation to ambient air (which can be significantly colder than snow).

When compared to the cold roof, the warm roof is less complicated to build and will insulate better. It is made with expensive materials, however, so may have a higher first cost—especially for owner-builders.

![]() A cold roqf

A cold roqf

Flat roofs, like sloped roofs, require ventilation to prevent heat buildup and to minimize condensation. The principles of ventilation are the same for flat roofs as for sloped roofs, but flat roofs have some particular ventilation requirements due to their shape. On a flat roof, a low intake vent can rarely be balanced by a high exhaust vent (3 ft. min. above the intake vent). The

net free-ventilating area therefore cannot usually be reduced from кІ50 of the area of the roof.

Flat-roof ventilators are commonly of the continuous strip type, located at a soffit, or a series of small vents scattered across the roof. Parapet walls can also provide effective ventilation for flat roofs (see 205B).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leave a reply