Copper is the preferred conductor for residential circuit wiring. Aluminum cable is frequently used at service entrances, but it is not recommended in branch circuits.

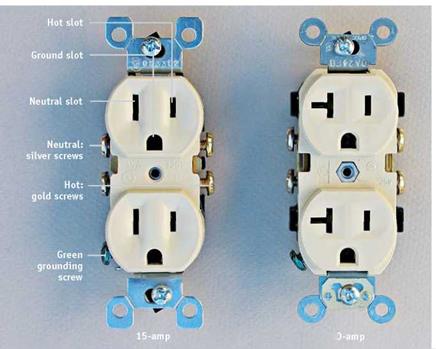

Individual wires within a cable or conduit are color coded. White or light gray wires are neutral conductors. Black or red wires denote hot, or loadcarrying, conductors. Green or bare (uninsulated) wires are ground wires, which must be connected continuously throughout an electrical system.

Because most of the wiring in a residence is 120-volt service, most cables will have three wires: two insulated wires (one black and one white) plus a ground wire, usually uninsulated. Other colors are employed when a hookup calls for more than two wires; for example, 240-volt circuits and three – or four-way switches.

BOXES

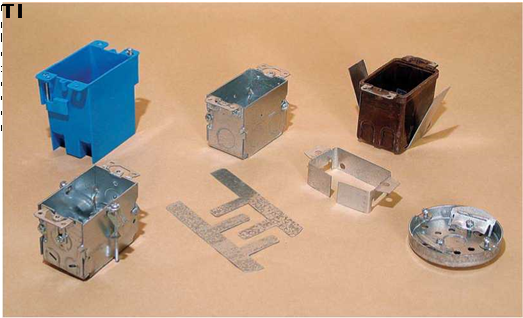

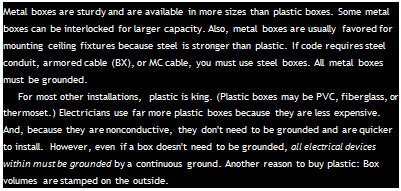

There is a huge selection of boxes, varying by size, shape, mounting device, and composition. But of all the variables to consider when choosing boxes, size (capacity) usually trumps the others. Install slightly oversize boxes, if possible: They’re faster to wire and, all in all, safer because jamming wires into small boxes stresses connections.

Aluminum wiring was widely used in house circuits in the 1960s and 1970s, but it was a poor choice. Over time, such wiring expands and contracts excessively, which leads to loose connections, arcing, overheating and—in many cases—house fires. If your house has aluminum circuit wiring, the most common symptoms will be receptacle or switch cover plates that are warm to the touch, flickering lights, and an odd smell around electrical outlets. Once arcing begins, wire insulation deteriorates quickly.

An electrician who checks the wiring may recommend adding COPALUM® connectors, CO/ALR-rated outlets and switches, or replacing the whole system.

Note: Aluminum service cable, thick stranded cable that connects to service panels, is still widely used because it attaches solidly to main lugs, without problems.

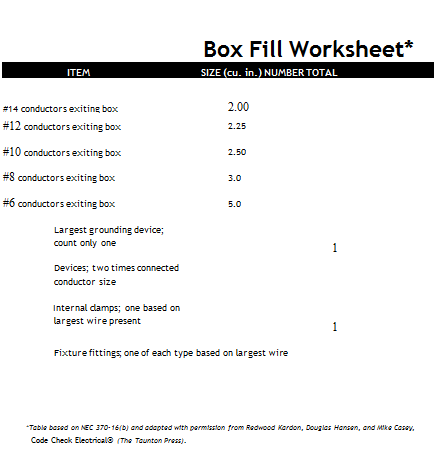

Capacity. The most common shape is a singlegang box. A single-gang box 3f2-in. deep has roughly 22Й cu. in. capacity: enough space for a single device (receptacle or switch), three 12/2 W/G cables, and two wire nuts. Double-gang boxes hold two devices; triple-gang boxes hold three devices. Remember: Everything that takes up space in a box must be accounted for— devices, cable wires, wire nuts, and cable clamps— so follow closely NEC recommendations for the maximum number of conductors per box.

You can get the capacity you need in a number of ways. Some pros install shallow foursquares (4 in. by 4 in. by 1И in. deep) throughout a system because such boxes are versatile and roomy. If a location requires a single device, pros just add a mud ring cover, as shown in the photo on p. 240. Because of their shallow depth, these boxes can also be installed back to back within a standard 2×4 wall. Thus you can keep even back-

to-back switch boxes at the same height, from room to room. Shallow pancake boxes (4 in. in diameter by J2 in. deep) are commonly used to flush mount light fixtures.

to-back switch boxes at the same height, from room to room. Shallow pancake boxes (4 in. in diameter by J2 in. deep) are commonly used to flush mount light fixtures.

Mounting devices. The type of mounting bracket, bar, or tab you use depends on whether you’re mounting to finish surfaces or structural members. When you’re attaching a box to an exposed stud or joist, you’re engaged in new construction or new work, even if the house is old. New-work

boxes are usually side-nailed or face-nailed through a bracket; nail-on boxes have integral nail holders. The mounting bracket for Veco® nonmetallic boxes is particularly ingenious (see the photos on p. 244). Once attached to framing, the box depth can be screw adjusted till it’s flush to the finish surface.

Adjustable bar hangers enable you to mount boxes between joists and studs; typically, hangers adjust from 14 in. to 22 in. Boxes mount to hangers via threaded posts or, more simply, by being screwed to the hangers. Bar hangers vary, too, with heavier strap types favored in walls, where boxes can get bumped more easily. Lighter hangers, as shown on p. 239, are typically used in ceilings, say, to support recessed lighting cans.

Cut-in boxes. The renovator’s mainstay is cut-in boxes because they mount directly to finish surfaces. These boxes are indispensable when you want to add a device but don’t want to destroy a large section of a ceiling or wall to attach to the framing. Several types are shown in the top photo at right. Most cut-in boxes have plaster ears that keep them from falling into the wall cavity; what vary are the tabs or mechanisms that hold them snug to the back side of the wall: screw – adjustable ears, metal-spring ears, swivel ears, or

bendable metal tabs (Grip – loks™). Important: All cut-in boxes, whether plastic or metal, must contain cable clamps inside that fasten cables securely. That is, it’s impossible to staple cable to studs and joists when they are covered by finish surfaces, so you need clamps to keep the cables from getting tugged or chafed by metal box’s edge.

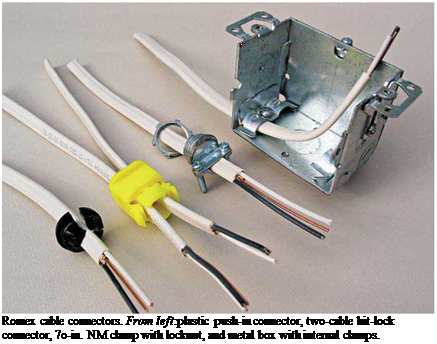

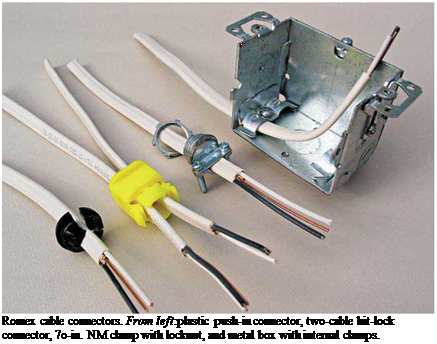

Clamps. Every wiring system— whether nonmetallic (Romex), MC, or conduit—has clamps (connectors) specific to that system. Clamps solidly connect the cable or conduit to the box so there can be no strain on electrical connections within the box and, as important, Romex clamps protect cable sheathing from burrs created when a metal box’s knockouts are removed.

GETTING BOX Edges FLUSH

GETTING BOX Edges FLUSH

Use an Add-a-Depth ring ("goof ring") to make box edges flush when an outlet box is more than ‘A in. below the surface—a common situation when remodelers dry – wall over an existing wall that’s in bad shape. To prevent the metal goof ring from short-circuiting screw terminals, first wrap electrical tape twice around the body of the receptacle or switch.

Posted by admin on 18/ 11/ 15

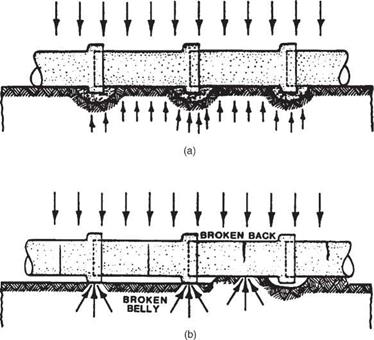

Inspection of reinforced concrete pipe should focus on problems with alignment, joints, and the wall.

The alignment of the culvert may be inspected visually. Misalignment may be caused either by poor installation practices or by subsequent settling of the pipe or the backfill. In any case, the pipe should be periodically monitored to ensure that the condition does not worsen. Close inspection of the joints may reveal conditions that will lead to an increase in the misalignment of the structure.

Joints should be inspected for cracks, separation, exfiltration, and infiltration. Cracks and separation of joints are detrimental to the culvert only insofar as they increase the possibility of infiltration and exfiltration. Infiltration is the inflow of water and the accompanying fines during times of high groundwater when the flow in the pipe itself is low. If the inspection is made during this time period and infiltration is occurring, it will be evident. If the inspection is made during a period when high groundwater is not present, but infiltration has occurred, there may be evidence of residual fines and silt at the joints. Infiltration can cause the loss of backfill and eventually lead to a failure of the roadway above as shown in Fig. 5.45.

Exfiltration is the outflow of water from the pipe into the surrounding backfill. This may cause piping, a loss of backfill material carried away by the outflowing water. This can create problems both with the roadway above and with the culvert itself, which can lose structural integrity because of the loss of side support. If exfiltration is occurring, it may be observed when the flow is relatively low by inspection of the joints. In addition, there may be some evidence of piping at the outlet end of the culvert, where undermining and the deposition of fines may be present.

Whereas loss of backfill support would be evidenced by excessive deflection in a flexible culvert, rigid culverts will not exhibit this condition. Despite the loss of backfill support, there may be little or no sign of distress in the wall of the culvert.

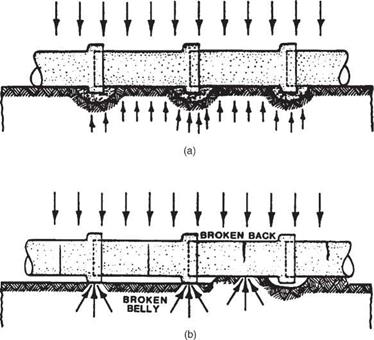

The walls of concrete pipe should be inspected for longitudinal and transverse cracks and spalls and wearing of the invert. Longitudinal cracks at the pipe crown or invert (cracks that run lengthwise down the culvert) are indicative of high flexural stresses in the pipe. As the pipe is loaded, it tends to deflect downward and outward. These deflections cause the inside of the pipe at the crown and invert to be in tension as well as the outside of the pipe at the springlines. If the pipe is subjected to a high load, longitudinal cracks may develop at these locations. Because the pipe is buried, inspection of the longitudinal cracks located at the springline on the outside of the pipe is not possible. However, the longitudinal cracks at the crown and the invert will be evident if they exist. Cracks 0.01 in (0.25 mm) or less in width are considered to be hairline cracks and are of minor importance. Larger cracks should be noted and monitored.

Longitudinal cracks located between the crown or invert and the springline are usually caused by shear failure of the wall section. If this type of cracking is visually observed, it is imperative that the cause of the cracking be investigated further. If a shear-type failure is determined to be the cause of the cracking, a rehabilitation or replacement strategy needs to be implemented immediately since the load-carrying capacity of the pipe has been compromised.

|

FIGURE 5.46 Illustration of transverse (circumferential) cracking in concrete pipe because of differential settlement. (a) Properly prepared bedding evenly distributes loads. (b) Improperly prepared bedding results in stress concentrations. (From "Culvert Inspection ManualReport No. FHWA-IP-86-2, FHWA, 1986, with permission)

|

Transverse cracks (cracks extending around the circumference of the pipe) are caused by differential settlement along the length of the pipe. This can be caused by either unsuitable foundation material or poor installation practices. These cracks are usually not structural in nature but can lead to spalling or subsequent corrosion of the reinforcing steel. Figure 5.46 illustrates transverse cracking resulting from improperly prepared bedding.

Invert wear on a reinforced concrete pipe or box culvert will be indicated by rutting of the surface or rust stains on the surface. In the extreme case, there will be exposed reinforcement. All of these conditions lead to a reduction in the structural adequacy of the culvert. Where the reinforcing is exposed, the bond is broken between it and the concrete and the reinforcing is not able to carry the intended stresses.

Unreinforced concrete pipe, whether cast in place or precast, should be inspected for invert wear and cracking. Because the concrete itself must take the flexural stresses, any reduction in thickness due to abrasive wear is of concern. For that reason, if rutting of the invert is evident, an attempt should be made to determine the amount of loss of section. The culvert should be reanalyzed for its structural capacity using this changed section to determine whether or not rehabilitation or replacement is necessary. If longitudinal cracks are present in unreinforced concrete pipe, the modulus of rupture has been met or exceeded and the flexural capacity of the pipe has been reached. As previously mentioned, only those cracks at the crown and the invert may be easily detected.

(See “Culvert Inspection Manual,” Report No. FHWA-IP-86-2, Federal Highway Administration.)

Posted by admin on 18/ 11/ 15

Contaminants may be held both in pore water and on/in the solids fraction of soil samples. Often it is desirable to know how much contaminant could be released from the sample. Simple separation of the pore water (e. g. by a centrifuge method) will not enable us to know how much contaminant might be released from the solids by desorption and leaching. To find this information, extraction tests of some kind need to be performed in which the contaminant is encouraged to move from the solids into the liquid phase by the arrangement of the tests. This is the subject of the first part of this section. Once the liquid phase has been extracted, chemical tests can be performed on the contaminated water – this is described in the second part of this section.

7.6.1 Extraction Methods

7.6.1.1 Introduction

Soils are complex matrices made up of numerous constituents with different and variable physical and chemical properties. Such constituents present variable capacities of interactions with pollutants, which drives the partitioning between the liquid and the solid phases. Pollutants of soils can thus be dissolved in the solution, can be adsorbed or make complexes with organic or inorganic constituents, or can be partially or totally transformed (bio-geo-chemical dynamic) (ADEME, 1999). All these forms are in relation and can, according to the type of matrix and the properties of the pollutant or external factors, induce an increase or a decrease in the mobility and (bio) availability of pollutants. These different forms can be extracted selectively from the matrix thanks to laboratory extraction methods using appropriate chemical reactants (Tessieretal., 1979; ADEME, 1999).

The environmental performance of a material is rather based on release than on total content of potentially dangerous constituents (van der Sloot & Dijkstra, 2004). Selective extraction procedures allow the assessment of the geo-chemical distribution of pollutants in the solid matrix (Colandini, 1997), and therefore the choice of extraction methods depends on the purpose of the investigation. This section essentially deals with inorganic pollutants.

Organic pollutants are often insoluble in water, though may be miscible by surfactants (e. g. detergents) or may exist in water as emulsions. Alternatively, the water and the organic chemical may be self-segregating leading to layered “oil” and other fluids, their relative positions dependent on relative density. Interaction of the organic fluid and solid is complex, depending largely on surface chemistry effects which will not be explained here (see e. g., Yong et al. (1992) for further information). Sorption of organic fluid is largely limited to organic solids.

Posted by admin on 18/ 11/ 15

The appropriate passage of material through the paver plays a key role in the proper spreading of a mixture. After starting in the hopper, the mixture is moved by slat conveyors (with flow gates in older equipment) to augers and then under a screed. During each of these stages the following significant parameters affect the final result:

• The hopper should be fitted with independently lifting wings, and its shape should eliminate places from which the mixture does not slide to the slat conveyor. Such “dead areas” or “cool corners” create accumulations of cool mixture and cause other problems (see Chapter 11). For the same reasons, the insulation of wings is desirable.

• Care should be taken so that the mixture does not adhere to the walls of the hopper where it cools off fairly quickly. These effects can be seen in various forms of segregation (see Chapter 11). It is perhaps worth dedicating one of the paving crew to systematically throw the cooled remains of mixture down in to the middle of the hopper, particularly when work is done on cool and windy days.

• Completely emptying the hopper of mixture should not be permitted. Newly delivered material should be added to the hopper when it is still filled to about 20% of capacity.

• Augers are intended to divide the mixture across the width of the screed plate; the quality of the layer’s surface depends, among other things, on appropriate adjustments to the augers. The amount of mixture supplied to the augers should be constant; it can be controlled by setting the slat conveyors’ speed and allowing an adequate opening of the flow gates (if applicable).

• The distribution of mixture at the middle of the paver screed plate has a significant influence on the segregation of an SMA mixture. In some machines, there is a feeding screw without a large chain transmission on the axis of the paver; rather the feeding screw is propelled from outside by hydraulic engines and intersecting axis gears.

• The screed plate must be fitted with a heating system. A number of solutions are available and include power supplies, heating fuels, and gas burners. A properly heated screed enables the appropriate travel of the mixture without dragging and pulling out particles.

• Screeds are fitted with vibration systems and rammers. The frequency and amplitude of vibrations and rammers’ strokes should be compatibly matched.

• To ensure quality of the placed layer, a constant paver speed should be maintained. Stoppages should be avoided.

| |

We won’t make much sawdust in this chapter. Instead, we’ll learn which tools and techniques are needed to install vinyl siding and prefinished aluminum coil stock. This plastic and sheet-metal exterior is quite different from the redwood siding and trim I used earlier in my construction career. Depending

We won’t make much sawdust in this chapter. Instead, we’ll learn which tools and techniques are needed to install vinyl siding and prefinished aluminum coil stock. This plastic and sheet-metal exterior is quite different from the redwood siding and trim I used earlier in my construction career. Depending

to-back switch boxes at the same height, from room to room. Shallow pancake boxes (4 in. in diameter by J2 in. deep) are commonly used to flush mount light fixtures.

to-back switch boxes at the same height, from room to room. Shallow pancake boxes (4 in. in diameter by J2 in. deep) are commonly used to flush mount light fixtures.