About 2800 or 2900 BC, the Sumerians – or perhaps a people already established somewhat to the north at Terqa – founded Mari, on the middle course of the Euphrates. The site is at the intersection of routes to the Syrian coast, near the outlet of the fertile valley of Khabur. This is not a village that has grown and evolved, but rather a “new city”. The region of Mari is completely arid, no agriculture is possible without irrigation. Yet 200 km to the north, at the toe of the Anti-Taurus mountains, one finds land that is naturally well watered. Therefore Mari must have been established where it is for reasons related to commerce and control of the waterway. The land of Sumer has to import raw material such as wood, stone, and metals. The early (and temporary) city of Habuba Kebira, further upstream, undoubtedly had the same needs. From the very beginning, Mari is a center of bronze metallurgy. Boats descending the Euphrates and the Khabur bring minerals and charcoal to the city.[56]

Mari falls under the control of Sargon of Akkad around 2300 BC. Its period of greatest grandeur occurs under a dynasty of Bedouin origin (called Amorite), capital of a great kingdom of upper Mesopotamia between 1850 and about 1761 BC. In 1761 BC it sees its final destruction by the Babylonian Hammurabi, even though Zimri Lim, last king of Mari, had helped Hammurabi in his wars against Larsa, Esnuma, and Elam. The palace fire buried, and preserved to the present time, the clay tablets that comprise the archives of the last thirty years of the kingdom.

The city of Mari is essentially circular in shape, surrounded by a dike and wall. The city is 1 to 2 km distant from the Euphrates, for protection from floods and erosion. It is crossed by a canal that links it to the Euphrates at each end. This canal is 30 m wide,

and brings water to the city as well as providing access to the port of Mari.[57]

The city’s water supply is from the Euphrates, lifted into it by manual labor; women carry the water and fill the palace’s cistern (Figure 2.9). But in the palace of the IInd millennium BC there is also a network of brick conduits or pipes (Figure 2.10) that collects rainwater from the terraces to fill a reservoir.

|

Figure 2.9 The cistern of the Mari palace – beginning of the IInd millennium BC (photo by the author).

|

In Chapter 1 we mentioned that Mari also benefited from a sort of drainage system, with sumps or cesspools for the drainage of rainwater and wastewater. This is evident from certain remains, as well as from palace texts:

“…On the subject of the sump, [….] according to the letter from my Lord, it is lined with asphalt from bottom to top. Over the layer of asphalt, there is a tar lining, and on top of that they put a coat of clay plaster.”

“After two rainstorms in succession, the sump was filled with water to a depth of a cane. The next day, they investigated it: 4 cubits of water had flown out. There remained 2 cubits, but they have already drained out ”[58]

Development of the land relies on major hydraulic works. Around 1850 BC, the second king of the Amorite Dynasty, Yahdun Lim, founds a fortress-city about a hundred

|

Figure 2.10 Channels for capturing rainfall on terraces of the Mari palace, beginning of the IInd millennium BC (photo by the author).

|

kilometers to the north of Mari, on the right bank of the Euphrates upstream of its confluence with the Khabur. He gives his name to the city, and endows it with a canal:

“Yahdun-Lim, the son ofYaggid-Lim, king of Mari, of Tuttul and the land of Hana, the strong king who rules the banks of the Euphrates; Dagan proclaimed my royalty (…). I opened canals, water-lifters were no longer needed in my country. I built the Mari wall and I dug its moat. I built the wall of Terqa and I dug its moat. Moreover, in the burning lands, in a place of thirst no king had been able to build a city, I, alone, had the vision and built a city. I dug its moat. I named it Dur-Yahdun-Lim. Then I opened a canal and named it Isim-Yahdun-Lim… ”[59] [60]

From texts cited further on, one can estimate that this canal is about 35 km long, a length necessary for the canal, with its flat slope relative to the Euphrates, to “raise" the water above the river to provide gravity irrigation of the crops. Traces of the canal remain visible today, but only in its upstream reaches.

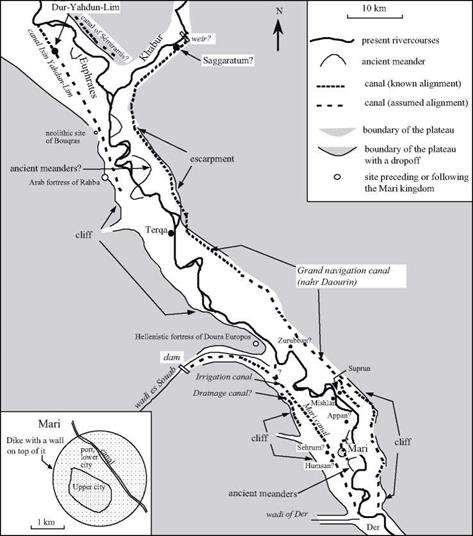

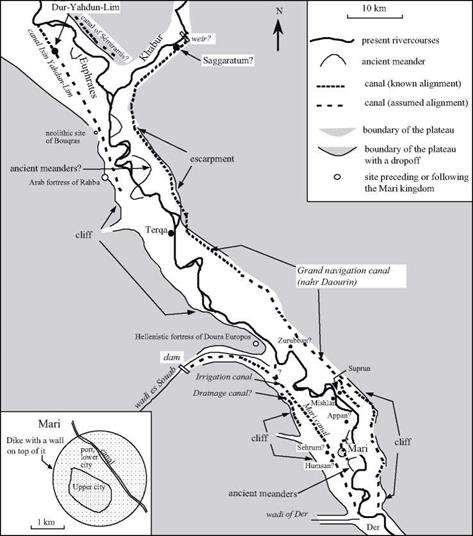

Field studies2 7 have uncovered traces of other important canals near Mari (Figure 2.11). There is a large irrigation canal, six to seven meters wide and 2.5 m deep, whose remains can be detected along a distance of17 km. It is not entrenched, but for the most part is constructed of fill on the alluvial terrace by means of massive dikes, 2.5 m high and 50 m wide. This is probably the Mari canal mentioned in the archives of the IInd millennium BC. Extracts that we cite further on suggest that the canal ends some ten kilometers downstream of Mari, and that it is supplied by an intake on the Euphrates in the valley of wadi es-Souab. But it is also quite possible that the canal dates from a time preceding these texts, having its origin in a small dam whose traces have been identified on wadi es-Souab, to the west of Mari. This wadi, one of the most important seasonal tributaries of the Euphrates, has particularly abundant springtime floods. The dam, 19 km from the confluence of the wadi with the Euphrates, is 450 m long, 2.5 m high, and has two spillways.[61] There is yet another canal that could have provided drainage, between the city and the foot of the cliff. Mari could not survive without some degree of agriculture, and such agriculture was impossible without irrigation. Therefore it is nearly certain that all these canals date from the founding of Mari, around 2800 BC.

Written communications[62] [63] [64] found in the Mari palace include numerous descriptions of the work necessary to maintain the irrigation system. The water intakes are often blocked by silt deposits and the canals themselves encumbered with sediments and vegetation that must be cleaned out annually. “Barriers”, apparently comprising tree trunks and branches, are placed to protect the intakes and limit deposits in their vicinity. Let’s listen to Kibri-Dagan, the governor of Terqa, in extracts from two different messages: “As for the work on the canal of Isim-Yahdun-Lim that I had to undertake the fifth of the month of Abum, I undertook it. It is considerable. I am going to proceed with considerable dredging. At this canal, the barrier-muba/litum that diverts the clayey silt toward the river is no longer there, and this has caused the canal to narrow near the river. (…) With my workers from the area, I am working on the interior of the canal. In ten days I will have cleaned out the reeds and brush down to Terqa, and there where the canal has narrowed, I will open it up again. I will be sure the work is done solidly so that the irrigation water will be blocked nowhere and so that the people can avoid famine.’0^

“At the end of the month of Abum, I gathered the servile and common people of my district and together with districts of Mari and of Saggaratum, I set out to open the blockage of the canal of Mari. However, before working on the canal of Mari, I used up all the water of the canal Isim-Yahdun-Lim for the upstream district, saying to myself: before the fields of the countryside of Terqa are irrigated, once water is available, the (upstream) district must be able to drink so that later on there will be no basis for protest.’01

|

Figure 2.11 Hydraulic works of the Mari kingdom, synthesis of archaeological and epigraphical research.

|

Other correspondence gives indications of the manpower available for this work. At this time, Terqa can mobilize 400 workers. But for major undertakings, the order of

2,0 workers can be assembled, as the governor of Mari, Bahdi Lim, explains:

“Tell my lord: thus speaks Bahdi-Lim, your servant. Concerning the wadi of Der (on the right bank, downstream), we got going on the dead (?) intake works and the diversion canal. The administrative scribes calculated the amount of work necessary. Beyond the dead intake works, there is the work needed for the diversion. A crew of 2,000 people, that’s not much! After thinking about it, we go to work only on the diversion. The work that we have under-

32

taken is good.”

The “barriers” mentioned above also play the role of raising the river’s water level at the intake to facilitate the outflow into the canal, without completely blocking the river. At this time there are six similar “barriers” on the Khabur designed to supply the irrigation canals. A letter from Yaqqim-Addu, governor of Saggaratum (whose supposed location is shown on Figure 2.11), describes these barriers and mentions a canal that provides water to the left bank of the Euphrates from the Khabur as an important element of the region’s irrigation system:

“The Habur (i. e. the Khabur), like the canal of Isim-Yahdun-Lim and the canal of Hubur (on the right bank, the north portion of the canal of Mari?), is part of our irrigation system. The people who profit from this irrigation canal never undertake to maintain it, and they have not reinforced the weak spots. I had to take on six barriers (muballittum) — who else could assure they would be watched over? When one wants to take water for the ditches, right where the trunks form fences, it takes 3,000 bundles of brushwood to make a piled-up barrier. But this doesn’t raise the Habur (the Khabur) a single finger! One must put in posts to form the fence:

one makes brushwood during ten days: one then piles them up to form barriers. Today this sys-

33

tem is damaged: alas! I am leaving for Habur; I am going to assess the damages.”

Later in this same letter, Yaqqim-Addu asks his colleague Dahdi-Lim, in charge of Mari, to loan him manpower, lacking which the Khabur flood will cause major damage: “At the present time, the Habur (the Khabur) is in flood at four cubits: it has covered all flood – able places. The dike-kisirtum that is upstream of the breach, downstream of the muballittu that we built, Kibri-Dagan and myself, had slipped. I am going to rebuild it. The side, at present, slipped again. I undertook to rebuild it. Moreover, the breach that we had closed up has reopened: two arches, made of brushwood, were installed. These various efforts have been considerable and have exceeded my means; my Lord needs to give instructions to Bahdi-Lim so that he will send me 200 men so I can reinforce the weak points on the Habur. If a breach occurs in the aforementioned dike, no one will be able to close it.”

One should not be surprised at how difficult it is to maintain these canals. As we have seen above, the slope of a canal must be less than that of the river, if the canal is to be used to irrigate terraces higher than the valley floor. The flow velocity must therefore be lower than that of the river, which favors the deposition of suspended silts in the canal.

The texts from Mari also show that fish farming is practiced at the beginning of the IInd millennium BC. The abandoned arms of the Euphrates are clearly exploited for this purpose, and it is again Kibri-Dagan who tells us about it:

“Tell my Lord, thus speaks Kibri-Dagan, your servant. When the river flood returned, the pond of Zurubban swelled and became larger than normal. This made me fear for the fish: there is a risk that the fish will leave the pond toward the river. Now a hundred people must come to make the water of the pond go toward the river.”[65]

Another text that we should cite tells us of a maneuver that makes the canal of Mari temporarily navigable, to carry boats loaded with grain from the harvest. All the secondary canal intakes were closed to raise the level in the main canal. But this turned out to be a catastrophe, since the rising waters caused the dike to rupture, just as the governor of Mari, Sumu Hadu (predecessor of Bhadi Lim) was taken to bed, sick:

“Tell my Lord, thus speaks Sumu-Hadu: one had retained the water in the direction of Der: because of the boats that must transport grain, one had blocked, from the upstream, (all) the irrigation ditches, and the water level thus rose (in the canal). But yesterday, at nightfall, in the end the water opened a breach upstream of the bridge that is the intake with the Balih (here, the Wadi Der), there where there is a water conduit (uncertain translation: a device allowing water diversion). Immediately, despite my sickness, I got up, I harnessed my asses, and I went to turn aside the waters by a derivation system. Then I came back to stop the water in the Balih (the wadi Der). Early in the morning, I undertook to repair the damage: I am going to rebuild the water conduit (?), after which I will get to work compacting the soil. This breach caused an opening of two canes from top to bottom, on a width of four canes. By the first watch of the night, I will have finished blocking this breach and I will be able (again) to let the water pass. My lord should not worry! Moreover, I wrote to the various localities that I had turned aside the water during the night. At Appan, Humsan and Shehrum, the water was held in and there was not the least rise. As for me, I will be dealing with the sickness that I have contracted for a year!’OJ

All of these documents show that the leaders had strong personal engagements in the maintenance of the irrigation system. They called on specialists, likely trained from father to son, for positioning the gates, for the operational regulation of the network. The regions of Terqa and Mari are not the only ones in which such water management is practiced; further upstream the Balih is used to irrigate the region of the city of Tuttul during the Amorite period.

![]()

Esthetic appeal. Normally, timber frames are left exposed, either on the interior, the exterior, or, in many cases, on both sides of the wall, such as the guesthouses and the garage at Earthwood. With many of the professionally built contemporary timber frame houses, structural insulated panels are fastened to the outside of the frame, and the beautiful heavy timbers are left exposed on the interior, (see Sidebar on page 13) At some 16-sided cordwood homes, the heavy timbers are in evidence on the exterior, but not on the interior. Chapter 6 of my previous book Cordwood Building: The State of the Art [see Bibliography] contains a detailed description of this almost-round timber frame. The method is of most interest to cordwood masonry builders, and is not repeated in this work.

Esthetic appeal. Normally, timber frames are left exposed, either on the interior, the exterior, or, in many cases, on both sides of the wall, such as the guesthouses and the garage at Earthwood. With many of the professionally built contemporary timber frame houses, structural insulated panels are fastened to the outside of the frame, and the beautiful heavy timbers are left exposed on the interior, (see Sidebar on page 13) At some 16-sided cordwood homes, the heavy timbers are in evidence on the exterior, but not on the interior. Chapter 6 of my previous book Cordwood Building: The State of the Art [see Bibliography] contains a detailed description of this almost-round timber frame. The method is of most interest to cordwood masonry builders, and is not repeated in this work.