If wood is the universal building stock, metal is the universal connector. Nails of many types as well as screws and bolts are discussed in this section. Specialty plates that reinforce structural members are also described. Later in this chapter is a review of construction adhesives, which, some say, are destined to supplant metal connectors.

NAILS

As they’re driven in, nail points wedge apart wood fibers. The ensuing pressure of the fibers on the nail shank creates friction, which holds the joint together. Nails also transmit shear loads between the building elements they join. Where nails join major structural elements, such as

Nail Sizes

Nail Sizes

|

1

|

2

|

|

112

|

4

|

|

2

|

6

|

|

212

|

8

|

|

3

|

10

|

|

314

|

12

|

|

312

|

16

|

|

4

|

20

|

|

412

|

30

|

|

5

|

40

|

|

6

|

60

|

rafters and wall plates, the loads can be tremendous; where nails attach finish elements, such as trim, loads are usually negligible.

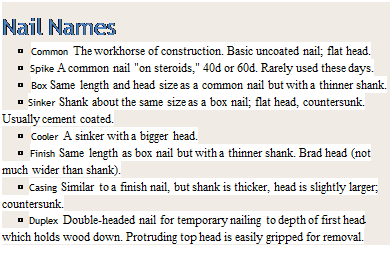

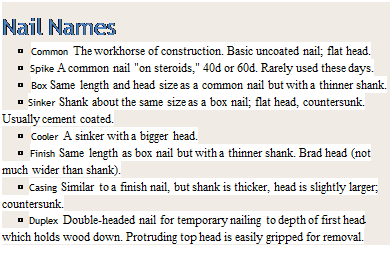

There are hundreds of different nails, which vary in length, head size, shank shape, point, composition, and purpose.

Length. Length is reckoned in penny sizes, abbreviated as d. The larger the nail, the greater the penny rating. Nails 20d or longer are called spikes.

Heads. The shape of a nail’s head depends on whether that nail will be exposed or concealed and what type of material it’s designed to hold down. Smaller heads—such as those on casing, finish, and some kinds of flooring nails—can easily be sunk below the wood surface. Large heads, like those used to secure roofing paper or asphalt shingles, are needed to resist pull-through.

Shanks. Nail shanks are usually straight, and patterned shanks usually have greater holding strength than smooth ones. For example, spiral flooring nails (with screw shanks) resist popping, as do ring-shank nails. (By the way, it takes more force to drive spiral nails.) Spiral and ring-shank nails are well suited to decks and siding because changes in wood moisture can reduce the friction between wood fibers and straight shanks.

Points. Nails usually have a tapered four-sided point, but there are a few variations. For example, blunt-point nails are less likely to split wood than pointed nails because the blunt points crush the wood fibers in their path rather than wedging

them apart. You can fashion your own blunt points by hammering down a nail point.

However, the blunt point reduces the withdrawal friction on the nail shank.

Composition. Most nails are fashioned from medium-grade steel (often called mild steel). Nail composition may vary, according to the following situations:

► Material nailed into. Masonry nails are case hardened. That’s also true of the special nails supplied with joist hangers and other metal connectors. Do not use regular nails to attach metal connectors.

► Presence of other metals. Some metals corrode in contact with others because of galvanic action (see "Galvanic Action," on

p. 70). So try to match nail composition to the metals present. The choice of nails includes

|

HOLES

|

Whenever you need to avoid bending nails in dense wood like southern pine and when you’re worried about splitting a joist because you’re nailing too close to the end, simply predrill a pilot hole. There’s no absolute rule to sizing pilot holes: 50 percent to 75 percent of the nail shank diameter is usually about right, letting the friction between nail and wood provide adequate grip.

aluminum, stainless steel, brass, copper, monel metal, and galvanized (zinc coated).

aluminum, stainless steel, brass, copper, monel metal, and galvanized (zinc coated).

► Exposure to weather and corrosion. Neither stainless-steel nor aluminum nails will stain wood. However, stainless is very expensive, and aluminum is brittle and somewhat tricky to nail. Galvanized nails, which are reasonably priced, will stain only a modest amount where the hammer chips the coating off the head. Therefore, you should seal galvanized nails as soon as possible with primer. Galvanized nails are also specified when framing with redwood

or treated lumber, both of which will corrode common nails. If you’re installing costly redwood or cedar siding, use stainless steel, especially if you’ll be sealing walls with a clear finish.

► Holding power. Nails that are rosin coated, cement coated, or hot-dipped galvanized hold better than uncoated nails. Vinyl – coated nails both lubricate the nail shaft as you drive it in (friction melts the polymer coating) and acts as adhesive once the nail’s in place.

Sizing nails. Common sense dictates the size of most nails. Generally, length should be about three times the thickness of the piece being nailed down. For sheathing J2 in. to M in. thick, use 8d nails (which are 2J2 in. long). Use 6d nails if the sheathing is ъ/ in. thick or less. Nail points should not protrude through the second piece.

The workhorse of framing is the 16d common, although 12d or 10d nails are good bets if you need to toenail one member to another. Use 10d or 12d nails to laminate lumber, say, as top plates, double joists, and headers.

When nailing near the edge or the end of a piece, avoid splits by using the right size nail, staggering nails, not nailing too close to the edge, blunting nail heads, or drilling pilot holes. Box nails, which have smaller-diameter shanks than common nails, are less likely to split framing during toenailing.

Pneumatic framing nails. When you’ve got a lot of nailing to do, say, to sheathe an addition, you may want to rent a pneumatic nailer. As noted earlier, it’s best to set nailer pressures so that nail heads stop just shy of a panel’s face ply. Then use a framing hammer to drive each nail flush. Most pneumatic framing nails are vinyl coated to make them hold well. And some pneumatic nail heads are colored, so you know immediately which size you’re loading.

Pneumatic nails differ slightly from common nails, however, so you may want to check your local building code before you rent a nailer. For example, pneumatic nailers load either coils of nails (coil nailers) or nails aligned in diagonal strips (stick nailers). Both work well, but some stick nailers accept only nails whose heads have been partially clipped. (Clipped-head nails pack more tightly.) Clipped-head nails are rarely a problem when nailing 2x lumber together, but plywood secured by the smaller nail heads is more likely to pull through under stress.

Second, pneumatic nail shanks are often thinner than those of common nails. In fact, some pneumatic 16d nail shanks are roughly the same thickness as 8d common nails used for nailing by hand.

SCREWS

SCREWS

Screws have revolutionized building. Thanks to a flood of specialized screws, builders can now quickly attach, detach, adjust, and reattach almost any building material imaginable. This is especially important in renovation, when you are scribing cabinets or setting door casing to walls that aren’t plumb—jobs that require patience and test positionings.

Heads. The increased use of cordless screw guns has made slotted screws almost obsolete. That’s because screws with traditional slot-drive heads let the driver blade slip out of the slot when torque is applied, but drive heads with centered patterns completely surround the point of the driver tip, holding it in place. Among the most popular drive heads are Phillips, square-drive, and six-pointed Torx®.

These days, screws are often engineered to specific uses. Trim-head screws have small heads like casing nails so they can be countersunk easily. Drawer-front screws have integral washers so they won’t pull though. Deck-head screws are designed to minimize “mushrooming” of material around the screw hole. Some structural screws have washer heads with beveled undersides so the screws will self-center in predrilled hinges or connector plates.

Threads. Screw threads are engineered for the materials they join. Traditionally, screws for joining softwoods are made of relatively soft metal with threads that are steep pitched and relatively wide in relation to the screw shaft. Screw threads for hardwoods and metal tend to be low pitched and finer. (The steeper the thread pitch, the more torque needed to drive the screw.) If you’re screwing into dense particleboard or MDF, predrill and then use Confirmat® screws, which have thick shanks and wide, low-pitched threads.

Many screws now feature self-tapping tips, in which a slotted screw tip drills its own pilot hole. Another ingenious design is a W-cut thread in which the threads nearest the tip are serrated like tiny saw points, so they cut through wood fiber as they advance. Such self-tapping features make it easy to drive in screws, without compromising holding power.

There are even screws that cut into concrete. Granted, you need to use a hammer drill to predrill an exact pilot hole, but once the pilot is drilled, you can use a 12-volt or 18-volt cordless screw gun, a standard!2-in. screw gun, or an impact screw gun to drive the screw the rest of the way. The threads grab the concrete and hold fast; the trick is not overtightening and breaking screws. Coatings. Coatings matter most on screws used outdoors or in high-humidity areas. Although

galvanized screws do resist rusting and are relatively inexpensive, don’t expect them to last much more than 8 years to 10 years on a deck—fewer years if used near saltwater. GRK Fasteners® promises “25 years in most applications” for its Climatek® coated screws. Makers of epoxy-, polymer-, and ceramic-clad screws offer varying life spans. The king of exterior screws is stainless steel—expensive, by far the most corrosion resistant, and the only suitable screw to prevent stains after attaching cedar or redwood.

|

BOLTS

Bolts are used to join major structural members, though with the advent of structural screws, the differences between the two are blurring. In general, machine bolts and carriage bolts have nontapering, threaded, thick shanks. Some bolts are more than 1 in. in diameter and longer than 2 ft. Allthread (threaded) rod comes in lengths up to 12 ft. and can be used with nuts and washers at each end. Carriage bolts have a brief section of square shank just below the head. Lag screws (also called lag bolts) have a hex head, but the lower half of the shank tapers like a wood screw.

WALL ANCHORS

|

|

|

Drywall SCREWS

Type W drywall screws are ubiquitous in renovation. (They are commonly called Sheetrock®, screws, after a popular brand of drywall.) Snug in a magnetic bit, drywall screws are also perfect for one-handed chores like centering door jambs before shimming. They’re especially loved by urban renovators because they can eliminate the need for hammering—the bane of neighbors. Also, where hammering might otherwise fracture existing wall surfaces, drywall screws join materials gently but firmly.

|

|

|

Anchors and bolts for light loads. From left: plastic anchor with screw, molly bolt, toggle bolt, and drive anchor.

|

|

|

Wall anchors employ small bolts or screws to attach light to medium loads (towel racks, mirrors, curtain rods) to drywall and plaster walls. None is designed for structural use. With the exception of drive anchors, most require a predrilled hole, and all expand in some manner so they won’t pull out easily. Molly bolts, drive anchors, and toggle bolts are best for attaching a light load to hollow walls. Wedge anchors, on the other hand, expand in solid masonry walls.

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]() ( K K E akXk = ^2 akMk

( K K E akXk = ^2 akMk![]()

Construction adhesives, caulk, and other sealants are ever present on job sites. Most of those products come in cylindrical cartridges that fit inside a caulking gun, which is used to apply the caulk or sealant. Construction adhesives can be used to bond different materials together—floor sheathing to floor joists, for example. To prevent water leakage, caulks are used to seal around windows and doorframes, at siding joints, and where a bathtub meets the floor. They can be used under wall plates and around pipe holes to block out cold air. Gaps between baseboards and walls or door casings can be filled with caulk before painting.

Construction adhesives, caulk, and other sealants are ever present on job sites. Most of those products come in cylindrical cartridges that fit inside a caulking gun, which is used to apply the caulk or sealant. Construction adhesives can be used to bond different materials together—floor sheathing to floor joists, for example. To prevent water leakage, caulks are used to seal around windows and doorframes, at siding joints, and where a bathtub meets the floor. They can be used under wall plates and around pipe holes to block out cold air. Gaps between baseboards and walls or door casings can be filled with caulk before painting.

The perception of affordable housing as something below par is not solely the result of this skewed terminology. The structures produced under the banner are usually as elephantine as the more expensive option, but with shoddier materials and even worse design. Through the eyes of the housing industry, square footage pays; quality does not.

The perception of affordable housing as something below par is not solely the result of this skewed terminology. The structures produced under the banner are usually as elephantine as the more expensive option, but with shoddier materials and even worse design. Through the eyes of the housing industry, square footage pays; quality does not.

у

у

![Foundation wall insulation Подпись: Snap chalkline to lay out the sill. The line shows where the sill's inside edge rests. If the foundation isn't perfectly square, adjust the line's position so that the sills will be. [Photo by Roe A. Osborn, courtesy Fine Homebuilding magazine © The Taunton Press, Inc.]](/img/1312/image193_1.gif) Most codes require that anchor bolts be located 1 ft. from each corner of the foundation, 1 ft. from the ends of each sill plate, and a maximum of 6 ft. o. c. everywhere else. These are minimum requirements. Builders living in earthquake or high-wind areas often use 5/8-in.-dia. anchor bolts rather than ‘A-in. bolts and reduce the spacing to 4 ft. o. c. or less. As mentioned in Chapter 1, it’s important to check with the local building inspector to ensure that the house you’re building meets or exceeds code.

Most codes require that anchor bolts be located 1 ft. from each corner of the foundation, 1 ft. from the ends of each sill plate, and a maximum of 6 ft. o. c. everywhere else. These are minimum requirements. Builders living in earthquake or high-wind areas often use 5/8-in.-dia. anchor bolts rather than ‘A-in. bolts and reduce the spacing to 4 ft. o. c. or less. As mentioned in Chapter 1, it’s important to check with the local building inspector to ensure that the house you’re building meets or exceeds code.![Foundation wall insulation Подпись: Test for square. One way to test foundation corners for square is to measure 6 ft. from the outside corner along one side and 8 ft. along the other. If til e til ird side of the triangle measures exactly 10 ft., you have a right angle. [Photo © Roger Turk]](/img/1312/image194_0.gif)

Nail Sizes

Nail Sizes aluminum, stainless steel, brass, copper, monel metal, and galvanized (zinc coated).

aluminum, stainless steel, brass, copper, monel metal, and galvanized (zinc coated).