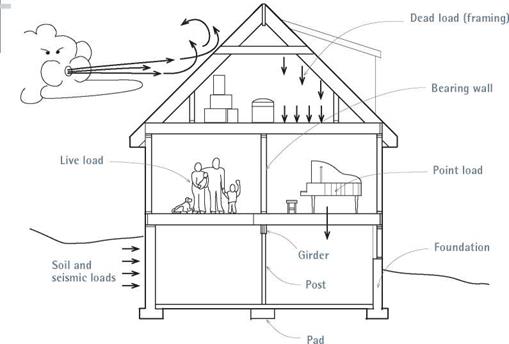

To assess the framing hidden behind finish surfaces, go where it’s exposed: the basement and the attic. Joists often run in the same direction from floor to floor.

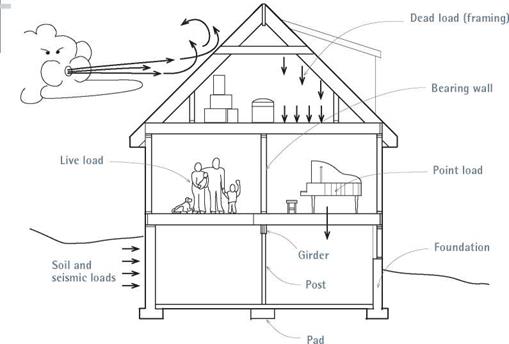

Generally, a girder (also called a carrying timber or beam) runs the length of the house, with joists perpendicular to it. Some houses will have framed cripple walls (short walls from the top of a foundation to the bottom of the first-floor joists) instead of a girder. Main bearing walls often run directly above the girder, but any wall that runs parallel to and within 5 ft. of a girder or cripple wall is probably bearing weight and should be treated accordingly.

Bearing walls down the middle of the house are also likely to be supporting pairs of joists for the floors above. That is, most joists are not continuous from exterior wall to exterior wall—they end over bearing walls and are nailed to companion joists coming from the opposite direction. This allows the builder to use smaller lumber—

2x6s rather than 2x8s, for example—to run a shorter span. If you cut into such a bearing wall without adding a header, the joists above will sag.

Large openings in obvious bearing walls are often spanned by a large beam or a header that supports the joists above. These beams, in turn, are supported at each end by posts within the wall that carry the load on down to the foundation. These point loads must be supported at all times. Similarly, large openings in floors (stairwells, for example) should be framed by doubled headers and trimmers that can bear concentrated loads.

Finally, it may be wise to leave a wall where it is if pipes, electrical cables, and heating ducts run through it. Look for them as they emerge in unfinished basements or attics. (^) Electrical wiring is easy enough to remove and reroute—but disconnect the power first! However, finding a new home for a 3-in. or 4-in. soil stack or a 4-in. by 12-in. heating duct may be more trouble than it’s worth.

Finally, it may be wise to leave a wall where it is if pipes, electrical cables, and heating ducts run through it. Look for them as they emerge in unfinished basements or attics. (^) Electrical wiring is easy enough to remove and reroute—but disconnect the power first! However, finding a new home for a 3-in. or 4-in. soil stack or a 4-in. by 12-in. heating duct may be more trouble than it’s worth.

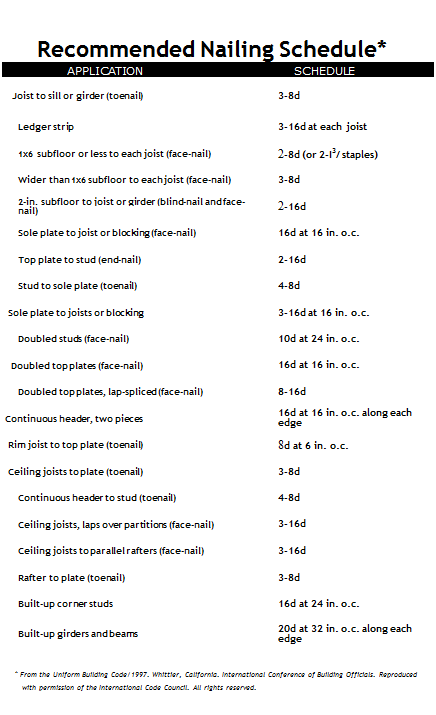

NAILING IT

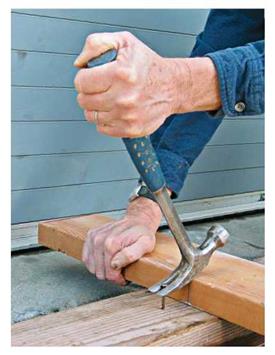

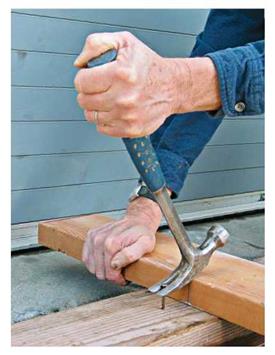

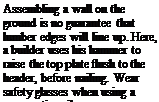

On larger renovations these days, pneumatic nailers do most of the work, but it’s worth knowing how to use a hammer correctly. Then you’ll create fewer bent nails, splits, and dings (dented wood when the hammer misses the nail), and perhaps avoid a smashed thumb, tendonitis, and joint pain.

The perfect swing. If you’re driving large nails such as 16d commons, start the nail with a tap. Then, with a relaxed but firm grip on the end of the hammer handle, raise the hammer head high and swing smoothly from your shoulder. If you’re assembling stud-wall elements, spread them out on a deck, put one foot on the lumber to keep it in place, bend forward slightly, and let the falling hammer head’s weight do some of the work. Just before striking the nail, snap your wrist slightly to accelerate the swing.

However, if you’re driving smaller nails (6d or 8d), you won’t need as much force to sink them. So choke up on the handle and swing from the elbow. Choking up is particularly appropriate if you’re driving finish nails because you’ll need less force and be less likely to miss the nail and mar the casing. It’s also necessary to choke up when there’s not enough room to swing a hammer freely or where you must drive a nail one-handed in a spot that you need to stretch to reach.

Work SAFELY

Put first-aid kits and fire extinguishers in a central location where you can find them quickly. Likewise, gather hard hats, safety glasses, hearing protection, and respirator masks at the end of each workday so they’ll be on hand at the start of the next.

I Loads and Structure

Plywooc

Plywooc

To nail plywood panels 1k in. thick or less, most codes specify 6d common nails spaced every 6 in. along the panel edges and every 12 in. in the field. Panels thicker than % in. require 8d common nails spaced in the same pattern. (Structural shear walls are typically nailed with 10d nails 4 in. to 6 in. on center along the edges and 12 in. on center in the field, but an engineer should do an exact calculation.)

Don’t overdrive nails. Ideally, nail heads should depress but not crush the face ply of the plywood. Panel strength isn’t affected if nail heads are overdriven by %6 in. or less, but if more than 20 percent of the nail heads are % in. or deeper, the American Plywood Association recommends adding one extra nail for each two overdriven ones.

Dnanm<>fif<.iiailav nmr. i______________________________________________________________________________ i

sure that’s too high is the most common cause of overdriven nails. It’s far better to set the nailer pressure so the heads are flush, and then use a single hammer blow to sink each nail just a little deeper.

NAILING TIPS

NAILING TIPS

|

A wood block under your hammer head makes nail-pulling easier.

|

|

|

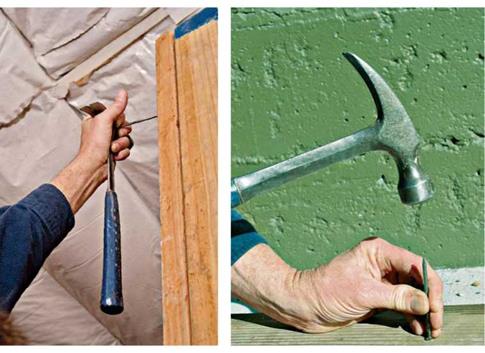

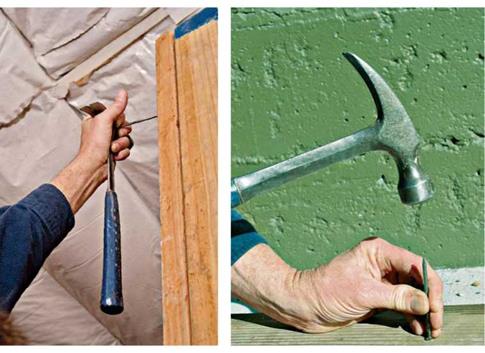

To nail where it’s hard to reach, start the nail by holding it against the side of the hammer and smacking it into the wood. Once the nail is started, you can finish hammering with one hand.

|

|

|

A blunted nail point is less likely to split wood because it will crush the wood fiber in its path rather than wedging it apart, as a sharp nail point does.

|

|

tion). In both cases, use house plans to position walls. Snap chalklines onto subfloors (or floors) to indicate wall sole plates. If you’re building a wall within a room, next measure from existing framing to determine the height and length of the new wall, as described in "Reinforcing and Repairing the Structure,” on p. 165. Finally, mark the locations of ROs, wall backers (blocking you nail drywall corners to), and studs into plates.

The easiest way to frame a wall is to construct it on a flat surface and tilt it up into place. Once the wall is lifted, just align its sole plate to a chalkline on the floor sheathing. This construction method is also stronger, because you can end-nail the studs to the plates rather than toe – nailing them. Sometimes, there’s not enough room to tilt up walls, a situation which is addressed later in this chapter.

I Stud-Wall Elements

If you use doubled 2x6s for your header in a rough opening in standard 8-ft. wall framing, you need cripple studs to support the doubled top plate. If you use a 4×12 instead, it will support the top plates. Although code may allow a single top plate for nonbearing walls, a single plate offers little to nail drywall to, if the ceiling is finished before the wall.

I Stud Layouts________

I Stud Layouts________

STUD-AND-PLATE LAYOUT

Mark stud edges on plates so that stud centers will be spaced 16 in. on center (O. C.).

|

Distances (O. C.)

48 in.

|

|

|

16 in.

|

16 in.

|

16 in.

|

|

|

|

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

<

|

|

X

|

|

|

X

|

<

|

|

151/4 in.

|

in.

|

|

|

|

31 1/4

|

Mark rough openings. Place the sole plate, face up, next to a chalkline; then place a top plate next to it, so that edges butt together and the ends align. Use a square to mark the top plate and the sole plate at the same time. (If the top plate is doubled, there’s no need to mark the upper top plate.) Using a tape measure, mark the ROs for doors and windows. Rough openings are so named because they are about 1 in. wider and 1 in. higher than preframed doors or windows (so units can be shimmed snug) and 2h in. wider and higher than unframed units.

As you mark the width of the RO on the plates, keep in mind that there will be a king stud (full length) and a shortened jack stud (also called a trimmer stud) to support the header on each side of the opening. After marking the ROs, mark the corner backers (also called wall backers)— extra blocking for drywall where partitions intersect with the wall you’re framing. "Corner-Stud Layouts” shows several backer configurations.

Mark studs on the plates. After marking the first stud, which is flush to the end of the plates, mark the subsequent studs 3з4 in. back from the red 16-in.-interval highlights on your measuring tape. (In other words, mark stud edges at 1514 in., 3114 in., 4714 in., and so on.) By marking stud edges 3з4 in. back, you ensure that stud centers will coincide with the edges of drywall or sheathing panels, which are usually some multiple of 16 in., for example, 48 in. by 96 in.

Mark studs every 16 in. on center on plates— through the ROs as well—so that drywall or sheathing panels running above or below open-

CORNER-STUD LAYOUTS Corners require at least three studs to provide adequate backing for finish materials. In the first example, the middle stud need not be continuous, so you can use pieces.

|

For standard 8-ft. wall framing, cut studs 92‘/4-in. long. One bottom plate and two top plates will be roughly 41yfe in. thick, creating a wall height of 963/ in. This height accommodates one drywall panel (*/! in. to 5/i in. thick) on the ceiling and two 4-ft.-wide drywall panels run horizontally on the wall. If you install a 4×12 header directly under the top plates of a standard wall, the rough opening height will be 821/ in. This is just right for a 6 ft. 8 in. door, and door head heights will match that of the windows.

|

ings can be nailed to cripple studs at regular intervals. At window openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on both the top and the bottom plates. But on door openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on the top plates only. Note: For door openings, where 16-in. on-center studs occur within 2 in. of a king stud, omitting the 16-in. on-center stud will not weaken the structure.

ings can be nailed to cripple studs at regular intervals. At window openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on both the top and the bottom plates. But on door openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on the top plates only. Note: For door openings, where 16-in. on-center studs occur within 2 in. of a king stud, omitting the 16-in. on-center stud will not weaken the structure.

Conserve when you can. If most of a plaster surface is sound, avoid damaging adjacent areas when removing loose plaster, exposing framing, or adding openings. For example, if you’re adding a medicine cabinet, set your circular-saw blade to the depth of the old plaster and lath, and cut back those materials to the nearest stud centers on both sides so the plaster edges can be renailed before you patch the opening.

Conserve when you can. If most of a plaster surface is sound, avoid damaging adjacent areas when removing loose plaster, exposing framing, or adding openings. For example, if you’re adding a medicine cabinet, set your circular-saw blade to the depth of the old plaster and lath, and cut back those materials to the nearest stud centers on both sides so the plaster edges can be renailed before you patch the opening.

could get ruined by the omnipresent dirt of tearout. At the end of the day, go there and relax.

could get ruined by the omnipresent dirt of tearout. At the end of the day, go there and relax. Cutting. Wear goggles when cutting out materials, for you’re likely to hit nails. Most blade makers sell demo blades, which are often carbide tipped and frequently thicker than standard blades. Reciprocating saws with demolition blades are the workhorses of renovation. Such blades typically have pointed ends that enable plunge-

Cutting. Wear goggles when cutting out materials, for you’re likely to hit nails. Most blade makers sell demo blades, which are often carbide tipped and frequently thicker than standard blades. Reciprocating saws with demolition blades are the workhorses of renovation. Such blades typically have pointed ends that enable plunge-

But if you’re raising a partition in an existing room, you’ll usually nail the top plate to ceiling joists. Invariably, space is tight indoors, and you’ll often need to gently sledgehammer the partition into place, alternating blows between top and sole plates till the wall is plumb. Alternatively, you can gain room to maneuver by first nailing the upper 2×4 of a doubled top plate to the exposed ceiling joists—use two 16d nails per joist—before raising the wall. Tilt up the wall, slide it beneath the upper top plate, plumb the wall, and then face-nail the top plates together using two 16d nails per stud bay. Finally, finish

But if you’re raising a partition in an existing room, you’ll usually nail the top plate to ceiling joists. Invariably, space is tight indoors, and you’ll often need to gently sledgehammer the partition into place, alternating blows between top and sole plates till the wall is plumb. Alternatively, you can gain room to maneuver by first nailing the upper 2×4 of a doubled top plate to the exposed ceiling joists—use two 16d nails per joist—before raising the wall. Tilt up the wall, slide it beneath the upper top plate, plumb the wall, and then face-nail the top plates together using two 16d nails per stud bay. Finally, finish

Finally, it may be wise to leave a wall where it is if pipes, electrical cables, and heating ducts run through it. Look for them as they emerge in unfinished basements or attics. (^) Electrical wiring is easy enough to remove and reroute—but disconnect the power first! However, finding a new home for a 3-in. or 4-in. soil stack or a 4-in. by 12-in. heating duct may be more trouble than it’s worth.

Finally, it may be wise to leave a wall where it is if pipes, electrical cables, and heating ducts run through it. Look for them as they emerge in unfinished basements or attics. (^) Electrical wiring is easy enough to remove and reroute—but disconnect the power first! However, finding a new home for a 3-in. or 4-in. soil stack or a 4-in. by 12-in. heating duct may be more trouble than it’s worth.

NAILING TIPS

NAILING TIPS

ings can be nailed to cripple studs at regular intervals. At window openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on both the top and the bottom plates. But on door openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on the top plates only. Note: For door openings, where 16-in. on-center studs occur within 2 in. of a king stud, omitting the 16-in. on-center stud will not weaken the structure.

ings can be nailed to cripple studs at regular intervals. At window openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on both the top and the bottom plates. But on door openings, you’ll mark cripple studs on the top plates only. Note: For door openings, where 16-in. on-center studs occur within 2 in. of a king stud, omitting the 16-in. on-center stud will not weaken the structure. If there’s room, assembling a wall on a flat surface and walking it upright is the way to go. This crew nailed restraining blocks to the outside of this second-story platform beforehand, so the sole plate couldn’t slide off the deck.

If there’s room, assembling a wall on a flat surface and walking it upright is the way to go. This crew nailed restraining blocks to the outside of this second-story platform beforehand, so the sole plate couldn’t slide off the deck. other, finer distinctions, including point loads, where concentrated weights dictate that the structure be beefed up, and spread loads, in which a roof’s weight, say, pushes outward with enough force to spread walls unless counteracted.

other, finer distinctions, including point loads, where concentrated weights dictate that the structure be beefed up, and spread loads, in which a roof’s weight, say, pushes outward with enough force to spread walls unless counteracted.

► Bracket hangers are usually lag screwed to fascia boards. They range from plain 4-in. brackets that snap over the back gutter lips to cast bronze brackets ornamented with mythical sea creatures. Brackets simplify installation because you can mount them beforehand—snap a chalkline to align them—and then set gutters into them.

► Bracket hangers are usually lag screwed to fascia boards. They range from plain 4-in. brackets that snap over the back gutter lips to cast bronze brackets ornamented with mythical sea creatures. Brackets simplify installation because you can mount them beforehand—snap a chalkline to align them—and then set gutters into them.