The process of performing a building inspection to address a client’s concerns is much more than taking instrument readings and reporting on the findings. A good building inspectorshould be part building scientist, part investigative journalist, part psychologist, and part building contractor. A nickname for the home inspector is"house doctor," which makes sense since the process of diagnosing and curing a sick home has many parallels to diagnosing and curing an ailing person.

The homeowner perceives a need and contacts the inspector to help address it. The building inspector’s job is to understand how a building is affecting the client or how environmental conditions are affecting the building. It is critical to ask the right questions. There is a pollutant affecting the client or the building; this pollutant has a reservoir within the building or an adjacent area of influence; and there is a pathway and a driving force

allowing the pollutant to come in contact with the person or building. This is true for everything from electromagnetic fields to moisture and mold to pesticides, a whole range of building pollutants that can be investigated and measured if one has the necessary tools and skills to make this invisible world visible.

Typically your first contact with the inspector will be a phone interview during which you explain in detail the history of your home, any changes you have made to it, and any changes you have observed in its feel, smell, and appearance overtime. A seasoned inspector, like a doctor, will beabletotakea good case history, askyou the right questions, and offer insights based on your experience and your concerns. This interview is critical to laying thefoundation for the inspection. Has remodeling, a recent pesticide application, or the installation of a new wireless phone or internet

Design for Responsiveness to the Natural Climate

In all but the most hostile environments, a home that is designed to be responsive to its surroundings will provide a wide range of opportunities for its residents to reap the health benefits of nature while reducing dependency on energy-consuming mechanical space conditioning.

• Good window design can greatly reduce dependence on mechanical heating and cooling. Placing windows to prevent overheating and to facilitate cross ventilation and solar gain when needed can result in both energy savings and a higher level of comfort. Proper window placement, the right type of window design, and glass

coating, used in conjunction with overhangs and trellises, can contribute to a successful home design.

• Proper room layout and window placement can also provide good natural lighting and a sense of well-being while reducing dependence on electrical lighting.

• Screened porches, overhangs, trellises, and patios can provide opportunities for extended outdoor living while acting as climatic buffer zones around the home.

• A paved entry path, covered entry porch, and foyer will reduce the amount of tracked-in dirt and provide a convenient place for shoe removal or cleaning, resulting in a cleaner home.

• An extension of the design process to

service occurred? All these conditions and more can affect sensitive individuals.

Even the most obscure building symptoms can be reduced by improving the environment.

An inspector is trained to treat buildings, not diagnose people, but improvements in the environment often lead to the improved well-being of a building’s occupants. Many autoimmune – type diseases find their beginnings in a sensitizing event. The focus of the inspector’s investigation will be attempting to discover the onset of this event and, based on the inspection and test results, recommending a means to minimize your exposure to whatever has made you ill and/or is making your building deteriorate.

Nature is the measuring stickfor a Building Biologist’s inspection. The baseline for elevated levels will be the natural surroundings. The interior of your home should have lower levels of dust, particulate matter, and mold than the surrounding outdoors. Your electromagnetic fields, especially in your sleeping area, should be minimal. During the course of the investigation the inspector may uncover other conditions of which you had no previous awareness but that can affect your health.

In my work as an inspector, my intention is to understand what is happening in the home or office and be able to present this information to my client in a supportive way. In other words, I cultivate a good "bedside manner."This is a critical aspect of the client/inspector relationship. The last thing I want is for the information I present to overwhelm my client or leave them feeling that conditions are outside their control. Remember, there is a natural or least toxic alternative to all our building challenges. Little changes built up over time can lead to big improvements. You can start by simply removing all the plug-in airfresheners and

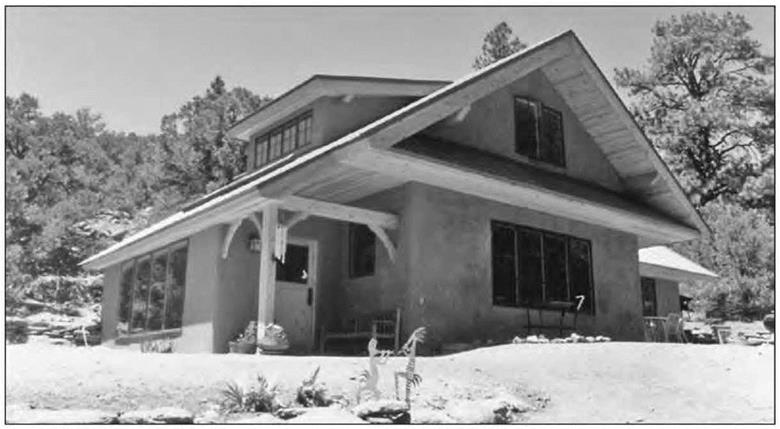

This entryway is designed for "tracking off" dirt and for shoe removal. It features a covered paved entry way and a sunken vestibule with easily mopped stone floors, that effectively keeps outside mud and dirt from finding its way into the home.

Photo: Paula Baker-Laporte.

installing pleated filters on the air conditioning system or letting more fresh air into your home.

After the client interview and building history, it is time to begin the physical investigation. The inspector will have formed a hypothesis of what is occurring within the building and will attempt to prove or disprove this hypothesis by taking the appropriate measurements with the appropriate instruments and testing devices. A typical baseline investigation targets a building’s systems and measures the operational conditions for a number of parameters, depending on the focus Just as the doctor will take your vital signs during a general checkup, the building inspector will begin the general investigation with measurements for temperature, humidity, moisture content, mold, airborne particulates, air exchange, chemical components, and electromagnetic fields, the building’s "vital signs" Further testing can be expensive

and is indicated only when the building inspector has cause for concern based on the results of the case history and initial inspection.

A Building Biology inspector will use Building Biology standards, which are based closely on a natural and healthy environment. Deviations from these standards indicate a departure from a healthy environment. The farther we progress away from a natural baseline, the unhealthier a building becomes. Building health is a measurable phenomenon when your inspector has the skills and tools.

Making positive changes to unhealthy building conditions will result in an improvement and a move toward the goal of a healthy building. Reductions in moisture intrusion will result in a drier building and prevent damage to building materials and also possible mold growth. Improvements in the temperature and humidity performance

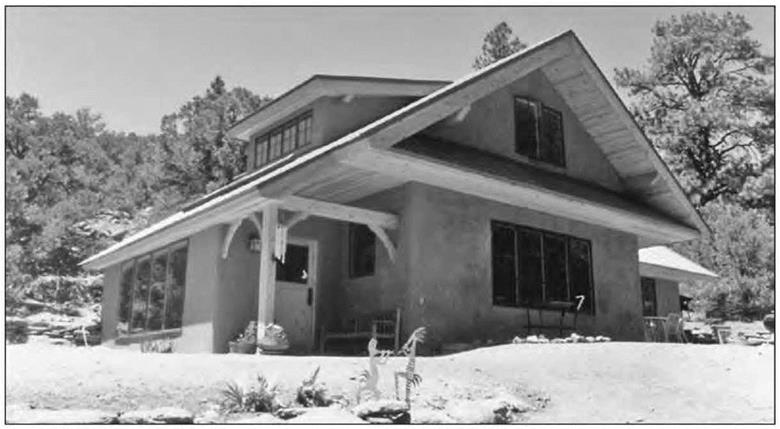

Deep roof overhangs and a covered entry help protect the natural wall elements of this straw – clay timber frame home. Architect: Paula Baker-Laporte; Builder: Econest Building Co.

Photo: Paula Baker-Laporte.

and filtration of an air conditioning system can be the difference needed to prevent a proliferation of dust mites (a prime allergen for asthmatics). Eliminating chemical pesticides and using common – sense natural pest control in their place will reduce exposure to neurotoxins that challenge immune systems. In short, Building Biologists are looking for ways to make buildings as healthy as possible. Build tight, ventilate right, and make conscious decisions about the materials you bring into your home. This is the house doctor’s equivalent of "eat right and get plenty of exercise and good rest" Maintaining a healthy home, like maintaining a healthy body, requires preventive "medicine." It is the homeowner’s job to become knowledgeable about and perform the necessary maintenance for the systems that keep the home healthy. This includes regular mechanical system maintenance, regular home cleaning with a good HEPA vacuum,

periodic changing ofwaterandairfilters, and minimizing exposure to electromagnetic fields and chemicals through prudent avoidance.

Will Spates has been practicing Building Biology for over 15 years and has been involved in the design, construction, and maintenance of environmental systems for over 30 years. He is the founder and president of Indoor Environmental Technologies, a testing and consulting firm that has performed over 4,000 inspections. He can be reached at wspates@IETbuildinghealth. com and at IETbuildinghealth. com.