I-JOIST CUTTING GUIDE

I-joists are awkward to cut because the top and bottom chords are wider than the web. To overcome this difficulty, make a simple jig with 3/4-in.-thick plywood. Cut a rectangular piece of plywood to fit between the chords and serve as the base of the jig. Screw a longer piece to the first piece, positioning it to guide a 90-degree cut. The edge of the top piece guides the base of the circular saw, as shown in the photo at right. Lay the guide on the I-joist, set the saw on it, and make a square cut. It’s that simple.

I-joists are awkward to cut because the top and bottom chords are wider than the web. To overcome this difficulty, make a simple jig with 3/4-in.-thick plywood. Cut a rectangular piece of plywood to fit between the chords and serve as the base of the jig. Screw a longer piece to the first piece, positioning it to guide a 90-degree cut. The edge of the top piece guides the base of the circular saw, as shown in the photo at right. Lay the guide on the I-joist, set the saw on it, and make a square cut. It’s that simple.

Cut I-joists with a guide. Scrap sheathing that is nailed or screwed together creates an effective guide for cutting I-joists. [Photo by Roe A. Osborn, courtesy Fine Homebuilding magazine © The Taunton Press, Inc.]

swell, shrink, crack, or warp the way solid lumber does. They are much lighter and easier to carry than 2x joists. And they’re uniform in size. In a load of 2x joists, you might find up to 3/8 in. of variation in joist width. I-joists don’t vary; once installed, they create a dead – level floor. Nails driven through the sheathing into the top chord are less likely to come loose and create a squeaky floor, especially when the sheathing is applied with adhesive. In terms of price, they are competitive with standard-

dimension lumber. Installation details for I-joists are slightly different than those for 2x joists. I’ll cover those differences just ahead.

Rim joists form the exterior of the building and are the first joists to be installed. The layout of other joist locations are marked on the top edges of the rim joists. Cut the rim joists to length and toenail each one flush with the outside of the sill. I drive one 16d nail every 16 in. around the perimeter (see the photo at left). Don’t forget that nails going into PT wood should be hot-dipped galvanized. In earthquake and high-wind areas, code may require that the rim also be secured to the sill with framing anchors, so check with your local building inspector. If there are no vents in the foundation, they can be cut into the rim joists. A standard screened vent fits in a 4//2-in. by 14//2-in. opening.

If you’re framing a floor with I-joists, you’ll probably use the specially made OSB rim joists supplied with your I-joist order. Install rim joists along only one side of the house. Then lay the I-joists flat across the sills, butting the end of each joist fast against the installed rim joist. The opposite ends of the joists will extend over the sill at the other side of the house. You can now

snap a line across the ends to establish where the I-joists need to be cut. A simple jig, explained in the sidebar on the facing page, makes it easy to cut the joists smoothly and accurately. After cutting the I-joists to length, complete the rim joist installation.

When a single joist spans a house from edge to edge, the layout is identical on parallel rims. Just hook a long tape on the end of the rim joist and make a mark on top every 16 in. (32 in., 48 in., etc.) down the entire length. Put an “X” next to each mark to indicate which side of the line the joist goes on.

When the joists lap over a central girder or wall, the layout on the opposing rim joists must be staggered. On one rim joist, mark the 16-in. o. c. locations with an “X” to the right; on the opposite side, lay out the joists with an “X” to the left. This allows the joists to lap and nail over a girder or crib wall, where they will be stabilized with blocks (see the illustration on p. 68).

|

![I-JOIST CUTTING GUIDE Подпись: With a little training, almost everyone can learn to safely use a nail gun to frame walls, though a trained professional or an experienced volunteer under supervision should use them. [Photo by Don Charles Blom]](/img/1312/image228_1.gif) |

Your joist layout may include openings (called headouts) for a stairway or to provide clearance for plumbing or vents. Your plans should show these openings, but it’s always a good idea (and it could save a lot of time and effort) to check with the plumber. A common mistake is leaving insufficient room between

Your joist layout may include openings (called headouts) for a stairway or to provide clearance for plumbing or vents. Your plans should show these openings, but it’s always a good idea (and it could save a lot of time and effort) to check with the plumber. A common mistake is leaving insufficient room between

Once the joists are cut to length and in position, carpenters say that it’s time to “roll” them. This just means setting the joists on edge, aligning them with their layout, and nailing them in place. If you are working with 2x joists, it’s important to sight down each joist to see whether there’s a bow or a crown, and then set the joist with the crown facing up.

Drive two 16d nails through the rim joist directly into the end of the joist—one nail near the top and one near the bottom (see the photo below). Most codes also require that joists be toenailed (one 16d on each side) to the sill plates and supporting girders. To nail off an I-joist, drive a 16d nail through the rim joist and into each chord, then nail the chord to the sill on both sides of the web.

Make sure that all the joists are nailed securely. This is important for safety reasons, for quality workmanship, and for meeting code requirements. Once all the joists are nailed upright, stop and check for symmetry—make sure the line of one joist is parallel with another.

![]()

the joists for the tub’s trap and the toilet’s drain. You may need to frame a headout to make room for plumbing. For headout framing details, see the sidebar on p. 67. When framing with I-joists, remember that, like any other type of engineered joist, they cannot be notched or cut midspan without destroying their structural integrity.

the joists for the tub’s trap and the toilet’s drain. You may need to frame a headout to make room for plumbing. For headout framing details, see the sidebar on p. 67. When framing with I-joists, remember that, like any other type of engineered joist, they cannot be notched or cut midspan without destroying their structural integrity.

If you trust your eye, try cutting 2x joists in place rather than measuring each one individually. As you become comfortable using a circular saw, you’ll be able make a square cut without using a square (see the sidebar on the facing page). This technique is definitely worth learning. Over the course of framing a house, it will save a significant amount of time.

If you trust your eye, try cutting 2x joists in place rather than measuring each one individually. As you become comfortable using a circular saw, you’ll be able make a square cut without using a square (see the sidebar on the facing page). This technique is definitely worth learning. Over the course of framing a house, it will save a significant amount of time.

![TOENAILING BASICS Подпись: The girders that support the joists need to break over a post. [Photo by Don Charles Blom]](/img/1312/image219_1.gif)

![TOENAILING BASICS Подпись: Plywood gussets tie girders securely to their post supports. [Photo by Don Charles Blom]](/img/1312/image220_0.gif)

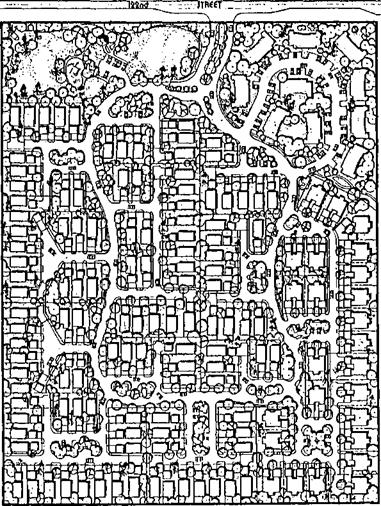

A majority of the projects in the Joint Venture for Affordable Housing (JVAH) were developed under some version of Planned Unit Development zoning or subdivision regulations.

A majority of the projects in the Joint Venture for Affordable Housing (JVAH) were developed under some version of Planned Unit Development zoning or subdivision regulations.

approach "provides a higher degree of regulation but permits the developer more flexibility in principal and accessory uses and of lot sizes than conventional zoning."

approach "provides a higher degree of regulation but permits the developer more flexibility in principal and accessory uses and of lot sizes than conventional zoning."

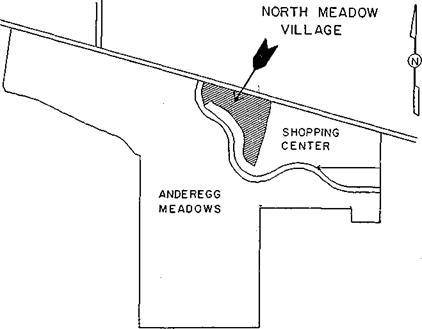

Black Bull Enterprises, Inc., developer of the affordable housing project "North Meadow Village," sought and secured from the city a number of innovative zoning modifications for the land parcel of which North Meadow Village forms one part. The parcel is situated in an area zoned for low-density, single-family construction at four units per acre. Black Bull requested establishment of a multifamily zone (22 units per acre) around a shopping center in the 150-acre tract located on a two-lane state highway, and a medium-density singlefamily strip (6.28 units per acre) separating the low-density singlefamily zone from the multi-family zone. In effect, he asked the Planning Bureau to trade higher densities in one portion of the tract for lower water and sewer usage in the commercial and retail area, with no net change in total water and sewer demand. The rezoning was approved by the city.

Black Bull Enterprises, Inc., developer of the affordable housing project "North Meadow Village," sought and secured from the city a number of innovative zoning modifications for the land parcel of which North Meadow Village forms one part. The parcel is situated in an area zoned for low-density, single-family construction at four units per acre. Black Bull requested establishment of a multifamily zone (22 units per acre) around a shopping center in the 150-acre tract located on a two-lane state highway, and a medium-density singlefamily strip (6.28 units per acre) separating the low-density singlefamily zone from the multi-family zone. In effect, he asked the Planning Bureau to trade higher densities in one portion of the tract for lower water and sewer usage in the commercial and retail area, with no net change in total water and sewer demand. The rezoning was approved by the city.

Under this city’s PUD, Holland Land Company was able to cluster homes, increase open spaces, and mix singlefamily detached units, duplexes,, and quadplexes in "Woodland Hills," a subdivision of HUD-code manufactured homes.

Under this city’s PUD, Holland Land Company was able to cluster homes, increase open spaces, and mix singlefamily detached units, duplexes,, and quadplexes in "Woodland Hills," a subdivision of HUD-code manufactured homes.

The study should examine each of the three principal stages of the application process and make recommendations for improving procedures at each stage, as follows:

The study should examine each of the three principal stages of the application process and make recommendations for improving procedures at each stage, as follows: City staff responsible for inspection must respond to builder and developer requests in a timely and scheduled manner. Developers and builders have a responsibility to assure that the work for which inspection is requested has been completed and meets the relevant criteria. Cities are justified in requiring that their time and expertise are efficiently used.

City staff responsible for inspection must respond to builder and developer requests in a timely and scheduled manner. Developers and builders have a responsibility to assure that the work for which inspection is requested has been completed and meets the relevant criteria. Cities are justified in requiring that their time and expertise are efficiently used.

The width of the joists and the length of the span determine how much support is needed. With 2×6 joists, for example, posts and girders are often placed every 6 ft. With 2 x12s or

The width of the joists and the length of the span determine how much support is needed. With 2×6 joists, for example, posts and girders are often placed every 6 ft. With 2 x12s or

Wait to carpet over concrete. Make sure you let a concrete slab dry out well (for several months) before laying carpet on it. If you don’t, the carpet adhesive may not hold properly and your carpet could rot, possibly posing a health hazard.

Wait to carpet over concrete. Make sure you let a concrete slab dry out well (for several months) before laying carpet on it. If you don’t, the carpet adhesive may not hold properly and your carpet could rot, possibly posing a health hazard.

Select an 18-in. by іУг-іп. by Vs-in. metal plate strap.

Select an 18-in. by іУг-іп. by Vs-in. metal plate strap. A bolt-hole marker makes it easy to transfer the bolt location to the sill in preparation for drilling a hole.

A bolt-hole marker makes it easy to transfer the bolt location to the sill in preparation for drilling a hole.

Place the sills over the bolts, put on the washers and nuts, and tighten the nuts with a crescent wrench, taking care to keep the inside edge of the sill on its layout. Note: When working on a slab, drill holes n the plates but leave them unbolted until after the wall is raised (see chapter 4 for details).

Place the sills over the bolts, put on the washers and nuts, and tighten the nuts with a crescent wrench, taking care to keep the inside edge of the sill on its layout. Note: When working on a slab, drill holes n the plates but leave them unbolted until after the wall is raised (see chapter 4 for details).