The minor lay lords of the middle ages were all too often uninterested in the management of the land, or sometimes were simply incapable of applying techniques that went beyond their competence. So it was the monks, and in particular the Benedictines and Cistercians, who became the custodians of land development during the demographic expansion of the 12th and 13th centuries. We have already seen that these monks were quite competent in such matters.

The biggest hydraulic project for reclaiming land from the sea and swamps was in coastal Flanders. Actually there were several distinct operations, but all of them were rather similar and conducted until about the year 1300. These projects were driven by recently founded abbeys, under the authority of the powerful Count of Flanders, with increasing involvement of the rich bourgeois toward the end of the period. The region was undergoing rapid economic and demographic growth during this period; in the 13th century Gand (with 64,000 inhabitants), Bruges (42,000) and Ypres (35,000) were, after Paris, the largest cities to the north of the Alps.

This story begins with the two major incursions of the North Sea in 1014 and 1042.

|

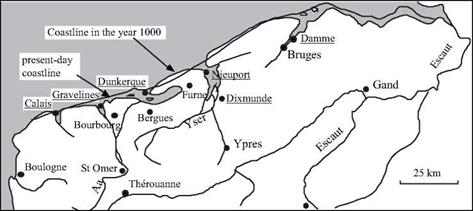

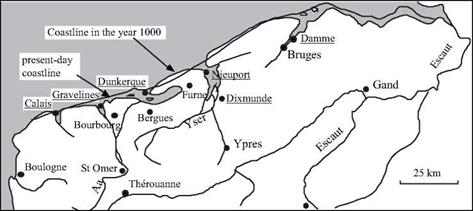

Figure 9.13 Coastal Flanders: shoreline in about the year 1000 (after Parisee, 1994) and after the channelization of rivers and compartmentalization of estuaries, which gave the coast its form from the end of the 13th century up to the present. The cities whose names are underlined are ports founded on reclaimed land in the 11th and 12th centuries.

|

Sheepraising was widely practiced on the floodable portions of the lowlands. These lowlands were protected by a line of dunes, but this line was broken by the sea incursions. The result was the formation of two large bays, one on the lower course of the Yser, the other to the northeast of Bruges in the region that is today called the Zwin. To protect the adjoining land from these new embayments, the inhabitants built long dikes more or less perpendicular to the coast in the middle of the 11th century. Examples are the 18-km long Oude Zeedijk (the “old sea dike”), that protects the area of Fumes from the Yser bay; and the Blankenberke Dijk to the northwest of Bruges. During this same period dike construction along the Yser River began downstream of its confluence with the Iepere, the river that flows to Ypres. This resulted in the founding of Dixmunde in 1089 as the seaport for the fast-growing city of Ypres.

Another major event occurred a half-century later, in 1134. This was a new incursion of the sea along all the coast of the North Sea, from Calais as far as the Frise islands to the north of the present-day Holland. This event seems to have marked the beginning of much more aggressive policies to combat the sea, first and foremost by the riparian abbeys. Dikes were progressively extended out from the land in large arcs, capturing the first polders (the term first appeared at this time) on the Yser and Zwin gulfs. Ultimately, these gulfs were completely dewatered in the 13th century.[480] The course of the lower Yser River resulted from these projects. The channelization of the river was completed in 1163, at which time the Count of Flanders, Thierry d’Alsace, founded Nieuport at the mouth of the river as the new seaport for the land of Ypres. In this same year he founded Gravelines, at the mouth of the Aa further to the west, and this in turn led to efforts to drain the marshlands of Saint-Omer and channelize the Aa, conducted from 1165 to 1215.[481] All of these projects were extremely difficult, as illustrated by the

text of a charter promulgated in 1169 by Philippe d’Alsace, the new Count of Flanders: “Between Watten and Bourbourg, a swampland had deposited silt over a vast expanse making it inaccessible and refusing of any human use. At my expense, I drained this muddy sea, at the cost of significant fatigue, and almost violently extracting from it a more favorable natural behavior, I transformed it into fertile land.’,z, H

In 1180 Philippe founds Dunkirk and Damme, the latter as a port on the Zwim River now conquered and channelized. The south bank of the Escaut River, to the west of Anvers, is similarly diked with the creation of polders. These projects began in the 12th century and without doubt were accelerated after a major flood of the Escaut in 1214; they were completed around 1300. The work was led by the neighboring abbeys, but surely also benefited from initiatives of the rich bourgeoisie of Gand and Anvers.[482] [483]

Public civil institutions called wateringues managed the hydraulic systems of Flanders, overseeing maintenance of the canals and gates and regulation of the channelized rivers and polders.

Another remarkable achievement is the development of the Poitevin marsh to the north of La Rochelle.[484] This vast zone of stagnant water surrounded by the waters of the Sevre, Vendee and Autize rivers, as well as by the bay of Aiguillon, had been the focus of modest developments up until the 12th century. The work included drainage and reclamation of lands bordering higher ground, and salt works. A few fishermen lived in the swamp itself. Villages and abbeys (Benedictine, Clunisian, Augustinian and Templar) are located on buttes that overlook the swamps, or on the edges of plateaus that border the swamp to the north.

In the middle of the 12th century the Cistercians settle on land that was ceded to them, further downstream and thus closer to the ocean than the land developed by their predecessors. These lands were far enough from the coast to be sheltered from dangerously high tides and storm surges. In ten years of work that ends at the turn of the century (around 1200), they manage to drain their marshlands using the technique of the “drying basin”. Aparcel of land is surrounded by a levee, called the “bot”, and then doubly bordered – outside of the levee by a canal connected to a system of “achenaux”, or channels, that convey the water toward the sea or into the Sevre; and on the interior by another canal right up against the levee, and fed by drainage ditches. The system can be controlled by gates in the levee, opened to evacuate the drained water into the hydrographic system, or closed to protect the basin from the inflow of high water. The peasant-fishermen living in the marshland are forced to leave. The principal players in this theater are: south of the Sevres, the Cistercians of Charron and other monasteries of the region, allies of the Templars of Bernay; and north of the Sevre, the energetic and dominant figure Ostensius, abbot of Moreilles until 1208.

But this reclamation of the Poitevin marsh has a negative aspect, namely its interference with the flow of water from the upstream Benedictine abbeys and villages to the sea. The first occupants of the threatened area are obliged to undertake additional work

to facilitate the seaward flow of floodwaters, while conserving the productive use of their own reclaimed land. From 1217 the “channel of five abbots” (l’achenal des cinq abbes”), a canal some 15 km in length, is constructed thanks to the coordinated efforts of the five large abbeys that occupied the land before the Cistercians arrived (Figure 9.14). Even later, in 1283, another long canal is constructed to connect the Lu$on canal to the “channel of the five abbots”. This canal makes it possible to drain the edge of the plateau upstream of the land reclaimed for Moreilles by the abbot Ostensius. For a change, this last canal, the “channel of the King” (l’achenal du Roi), does not owe its existence to the monasteries. Since the campaigns of Philippe Auguste and the Treaty of Paris, signed by Saint Louis in 1259, the south of the Poitou is royal land. This canal is thus built under the authority of the King with the financial participation of twelve lay

|

watercourse or canal assumed to be from before the 12th century

|

Bernay

|

canal (achenal)

|

|

|

towns and villages

|

|

|

abbeys: "dry land"

|

|

V J

|

|

Cistercian (above

|

|

Nuaille

|

Benedictine the marsh)

|

|

v

|

|

Templar

|

|

communities on the plateau.

The energy and hydraulic know-how of the Cistercian monks is seen in many other projects. To the north of Brives the Obazines achieve drainage of the land in the 13th century. They also developed the saltworks of Oleron. The Cistercians of Buzay play an important role in reclamation of marshlands in the Loire River delta.

Again in the Loire valley downstream of Tours, settlements had for ages been built on sandy fluvial deposits, and subsequently kept above the water by the inhabitants through accumulated fragile defenses of earth and turf. In the years 1160 – 1170, undoubtedly at the initiative of the English King Henry II Plantagenet, the first levee on

the Loire is built in the valley of Authion on the north bank of the river, extending some fifty kilometers between Langeais and Saumur. This is a turcie, a structure made of driven stakes, branches, sticks, and earth. Henry II settles inhabitants on the structure itself and charges them with the maintenance of the turcie; for this service, they are exonerated from military duty. All of this is laid out in a charter dated in 1169. In the 14th century this levee is extended downstream until it is continuous along all the valley of Authion. Large settlements like Tours and Orleans are in their turn protected by similar turcies. This leads to a period of calm along the Loire until the middle of the 15th century, perhaps explaining the neglect in maintenance of these levees. But important and repeated floods cause inundations in 1456, 1482, 1494, and again in 1519, 1525, and 1527. Starting in 1482 King Louis XI undertakes to raise the existing turcies, to generalize the flood defense system, and even to set standards for the height and the method of construction of the levees. This effort is continued until the reign of Henry IV.[485]

|

Another enterprise of grand amplitude is the development of the plain of Roussillon – but in a completely different context.[486] Roussillon is in effect part of the Catalan territory. In the 10th and 11th centuries it is part of the county of Barcelona, then a possession of the King of Majorca from 1262 to 1344, and finally it is integrated into the kingdom of Aragon. The land needs irrigation much more than drainage, and it seems logical that the influence of Andalusian techniques is found there. Irrigation networks develop in the basin of the Tet, east of Perpignan, from the 9th century; they particularly flourish between the 12th and 13th centuries (Figure 9.15). The influence of certain abbeys such as those of Lagrass and of Saint-Michel de Cuxa would appear to be decisive insofar as these irrigation works are concerned. As is the case in so many of the fertile regions of Europe, one finds ample evidence of donations of canals and mills from local lords to these abbeys.

Figure 9.15 The canals in the Roussillon plain: irrigation from the 11th to the 13th century; the “royal Thuir canal” and its wanderings of the 15th century, after Caucanas, 1995.

At the beginning of the 14th century the development of the cities of Perpignan and Thuir led to a major project to supply water necessary for cultivation, mills, and domestic use. The “royal canal of Thuir” was built by the king of Majorca at the very beginning of this century. The canal is 35 km long, rising in the foothills near Vinfa and crossing a hilly countryside. The terrain required that the canal be laid on a slope in some areas, necessitating numerous civil engineering works, and in particular several bridge – canals. The canal supplies six mills at Thuir, and seven at Perpignan where in addition it powers a noria that lifts water to the chateau. But the Mediterranean climate, with its violent floods, is a constant threat to this canal. In 1403 flood damages require that the canal be temporarily closed. It was necessary to rebuild the intake, which was accomplished by 1416, but then the canal is again destroyed by the major inundations of 1421. At this point the actions of the Arragon sovereigns are decisive. In 1425 a new canal, the “royal rech of Perpignan”, rejoins the trace of the earlier canal downstream of Thuir. The sole purpose of this canal, issuing from an intake at Ille further downstream, is to provide water for the city of Perpignan. As for the city of Thuir, the “royal rech of Thuir” is built two years later with an intake on the Tet River at an intermediate location between Vinfa and Ille (Figure 9.15). Later still, the lord of Corbere has the ancient royal canal of Thuir rebuilt to supply water to his city.

There are times when sewage pumps must be used to get sewage to a septic system. The pumps are normally installed in a buried box outside of the building being served. The box is often made of concrete. In these cases, the home’s sewer pipe goes to the pumping station. From the pumping station, a solid pipe transports the waste to the septic tank.

There are times when sewage pumps must be used to get sewage to a septic system. The pumps are normally installed in a buried box outside of the building being served. The box is often made of concrete. In these cases, the home’s sewer pipe goes to the pumping station. From the pumping station, a solid pipe transports the waste to the septic tank.