The key to economical wall and partition construction is preplanning to eliminate unnecessary materials and labor. Carpenters usually find extra material is needed here and there to accommodate doors and windows.

They may also follow traditional training by adding studs where partitions intersect exterior walls, blocking at mid-height of walls, double studs and headers at openings in nonbearing walls, and similar practices. Each of these excessive material uses is avoidable through proper attention in the planning stage. They add significantly’to cost without benefit to the home buyer.

Cost savings will be greatest when the overall out-to-out dimensions of the house and the location of wall openings coincide with a module of 2 feet. This provides maximum use of materials that are available in 2-foot increments and reduces scrap and waste.

An important side benefit to preplanning will be education of the carpentry crew. When the crew has built a number of units in accordance with cost saving techniques presented in this section, less detailed instructions and fewer on-site modifications will be required.

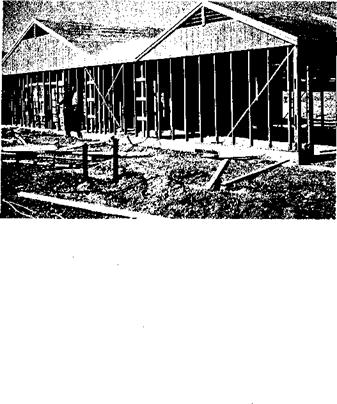

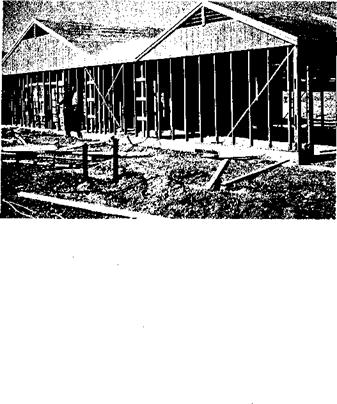

Tilt-up wall construction continues to be the preferred method for reducing labor and material costs. Assembling wall sections to the greatest extent possible prior to erection is beneficial since materials do not have to be held up while they are being fastened. This includes framing and sheathing (if used), as well as siding, windows and exterior trim. Fabrication can be done on a shop table or right on the floor deck. Use end nailing, not toe- nailing, to fasten plates to studs.

Engineering analysis and testing have resulted in widespread acceptance of many changes in traditional wall framing techniques. Many of these OVE (Optimum Value Engineered) techniques were developed and tested by NAHB National Research Center.

Engineering analysis and testing have resulted in widespread acceptance of many changes in traditional wall framing techniques. Many of these OVE (Optimum Value Engineered) techniques were developed and tested by NAHB National Research Center.

Building 7’6"high walls instead of 8’0" saves approximately one course of siding or two courses of brick, 6 percent of wall insulation, 3 percent of painting labor and material, one tread and riser on a flight of stairs, and 9 to 12 inches of stair landing space.

A lower ceiling height also increases the structural capacity of studs acting as a column. The savings in material and labor more than offset the extra labor to cut 6 inches from the top of the gypsum wallboard panels.

Placing studs 24 inches on center, instead of 16 inches, reduces framing labor and material. The 24-inch on – center spacing is permitted in most areas of the country for one story and the second story of two story construction. Use of 24 inch spacing saves nearly a third of the regular studding.

Single top plates can be used when studs and trusses are in line on 24- inch centers so that the weight of the truss bears directly on the stud. Special connectors to splice joints in the top plate or to tie corners are not required because the floor or roof system attached to the top plate serves this function. This technique eliminates one-third of the plate material.

When studs sit directly over floor joists, the bottom plate is used only to facilitate alignment of the studs, and to provide a nailing base for wallboard, sheathing and baseboard, and not to carry weight from the stud

to the joist. Since the bottom plate doesn’t have to be as strong, a 1×4 is sufficient.

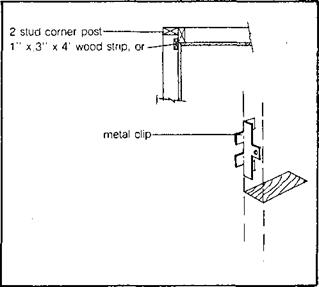

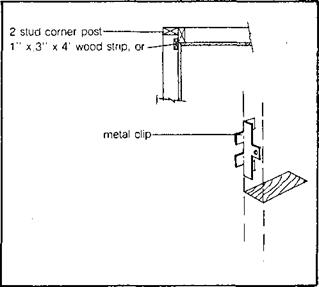

Because the maximum load on the corner studs in an exterior wall is one-half or less than the load on a regular stud, two-stud comers are more than adequate structurally. The third stud in the normal three-stud corner post serves only to back up the interior finish, and can be eliminated. Metal drywall clips or wood blocks can be used to backup the wallboard.

Similarly, partition posts built into the exterior wall for attachment of. interior partitions can be eliminated. The partition can be nailed to a midheight wall block, and wood blocks or drywall clips can be used to backup the wallboard.

Ceiling nailers can be replaced with drywall clips. Since they secure the ceiling gypsum board to the walls, the clips offer the additional advantage of keeping the ceiling and wall gypsum board from separating. Midheight "firestop" wall blocking can be eliminated. Wall plates, floor sheathing, and insulation provide sufficient constriction of air flow within the wall to minimize fire spread, and the blocking is not required for structural bracing.

Headers or lintels, and jack (jamb) studs which support them are required only where loads must be carried to the sides of window and door openings. If the loads don’t exist, or if other members, such as roof trusses, joists, joist bands, large areas of structural sheathing, or second story headers carry all or part of the loads across the openings, headers can be eliminated or downsized.

Openings in nonbearing walls can have single 2×4’s on each side to which windows and doors are fastened.

Headers and jack studs can also be eliminated in load-bearing walls when windows 22 1/2 inches or less in width are used and placed between the studs.

Other types of headers may be more economical than the single or double 2×8 header. Glue-nailed plywood box headers normally cost less and also provide extra space for insulation.

These headers are formed by glue- nailing a plywood skin to one or both sides of framing members above openings in a load-bearing wall.

Water resistant structural adhesives of the casein, urea formaldehyde, urethane or phenolresorcinol type should be used to glue the plywood, and nails spaced 6 inches or less along all frame members. .

The face grain of the plywood must be oriented horizontally over the opening, and the top plate must be continuous across the opening. Jack studs are not necessary on openings 4-feet wide or less. Use American Plywood Association exterior grade AC plywood.

If used on the inside surface, butt gypsum board to the plywood, tape and spackle the joint, and apply a thin coat of spackling compound to any plywood rough spots or patches. When* painted, there is no apparent difference between the plywood and gypsum board surfaces.

Manufactured plywood joists and trussed joists can also make cost- effective headers while providing room for extra insulation. Check with the manufacturer for engineered sizes and prices.

Brick veneer costs can be reduced by: starting the brick at floor joist level on 8-inch blocks resting on 16-inch footings, instead of below grade on 12-inch blocks resting on 20-inch footings; using other materials above and below windows and in areas less subject to deterioration, e. g., the gables and the top half of a wall; building the walls 7’6" high instead of 8 feet.

Single-layer panel sidings (plywood and hardboard) are available for application directly to studs, eliminating the need for a separate sheathing.

Returning gypsum wallboard to the

windows and using drywall corners instead of using wood stool and casings saves money. Similarly, using drywall returns on bi-fold or bypass closet doors eliminates wood jambs and casings.

Providing a full width opening at the front, dimensioned to receive a standard width bi-fold or sliding door, eliminates jacks and studs beside the opening, and floor-to-ceiling doors eliminate framing and drywall over the opening. Drywall contractors often charge for a full wall even if only partially covered.

Interior nonbearing partitions can be built from 2×3 studs. Also, if floor sheathing is 5/8 inch or thicker, no blocks or joists need to be framed below nonbearing partitions. Where partitions are parallel with ceiling joists or roof framing overhead, use precut 2×4 blocks spaced 24 inches on center to secure the top of the partition and to provide drywall backup.

Cabinet bulkheads can be eliminated. Install ceiling high cabinets, or let the top of standard height cabinets be an extra "shelf.

Light gage steel studs have been available for a number of years and are used extensively in commercial and high-rise apartment construction. They are usually installed by the drywall contractor. Steel studs are often cost effective, especially when lumber prices are high, but have not been widely used in single-family or low-rise multi-family construction.

Engineering analysis and testing have resulted in widespread acceptance of many changes in traditional wall framing techniques. Many of these OVE (Optimum Value Engineered) techniques were developed and tested by NAHB National Research Center.

Engineering analysis and testing have resulted in widespread acceptance of many changes in traditional wall framing techniques. Many of these OVE (Optimum Value Engineered) techniques were developed and tested by NAHB National Research Center.

Phillips designed and built a system that used 2x6s, spaced 24 inches on center, spanning about 8 feet between post-and-beam supports. Band joists were eliminated. Floor framing did not come into contact with the perimeter foundation at all. The first interior support girder was placed about 4 feet from the foundation wall and the joists cantilevered about 2 feet toward the foundation.

Phillips designed and built a system that used 2x6s, spaced 24 inches on center, spanning about 8 feet between post-and-beam supports. Band joists were eliminated. Floor framing did not come into contact with the perimeter foundation at all. The first interior support girder was placed about 4 feet from the foundation wall and the joists cantilevered about 2 feet toward the foundation.

Tom Webb designed and built a cantilevered front porch deck by continuing the interior stair landing joists through the front door opening. This eliminated deep porch footings and foundations which are very susceptible to frost heave in Fairbanks.

Tom Webb designed and built a cantilevered front porch deck by continuing the interior stair landing joists through the front door opening. This eliminated deep porch footings and foundations which are very susceptible to frost heave in Fairbanks.

Construction and materials. For exterior doors, wood is the traditional favorite, but it requires a lot of maintenance. Consequently, wood doors come clad in vinyl or aluminum, and good-quality, insulated steel doors are virtually indistinguishable from wood once they’re painted. Fire codes require steel doors between living spaces and attached garages or workshops. Exterior doors should have integral weatherstripping.

Construction and materials. For exterior doors, wood is the traditional favorite, but it requires a lot of maintenance. Consequently, wood doors come clad in vinyl or aluminum, and good-quality, insulated steel doors are virtually indistinguishable from wood once they’re painted. Fire codes require steel doors between living spaces and attached garages or workshops. Exterior doors should have integral weatherstripping.

ачіш

ачіш

The steps outlined in the next pages follow the process of framing and sheathing the exterior walls in a horizontal position. The fully framed and sheathed wall is then lifted into position by using special lifting jacks or muscle power.

The steps outlined in the next pages follow the process of framing and sheathing the exterior walls in a horizontal position. The fully framed and sheathed wall is then lifted into position by using special lifting jacks or muscle power.