Hierarchy

Good home design entails a lot of categorizing. The categories we use are determined by function. In organizing a home, everything that is used to prepare food would, for example, most likely go into the "kitchen” category. If something in the kitchen category functions primarily to wash dishes, it would probably be placed into the subcategory of "kitchen sink area.” The categories proposed by our predecessors usually serve as pretty good tools for organizing a home. Ideas like "kitchen,” "bathroom,” and "bedroom” stick around because they generally work. But these ideas cannot be allowed to dictate the ultimate form of a dwelling; that is for necessity alone to decide.

Sacred Geometry

Organizing the tops of windows and doors along a horizontal axis and deliberately spacing porch posts in a row are examples of the ways alignment and proportion can be consciously used to create a structure that makes visual sense. Less obvious examples become apparent when regulating lines are drawn on photos of a building’s facade. These lines are stretched between significant elements, like from the peak of the roof to the cornerstones, or from a keystone to the baseplates. When geometry has been allowed to dictate the rest of the design, the lines will almost invariably intersect or align with other crucial parts of the building. The intersections are often unexpected, their appearance the unintended biproduct of the creative process described on these pages.

Do not think that, just because our shared idea of "bathroom” includes a bath, a sink and a toilet, that these things must always be grouped together behind the same door. The needs of a particular household may determine that each be kept separate so that more than one can be used at a time. What is more, if the kitchen sink is just outside the door to the toilet, then a separate basin may not be necessary at all. The distinctions made between the categories of "living room,” "family room” and "dining room” might well be combined into the single category of "great room” for further consolidation.

Vernacular designers do not thoughtlessly mimic the form of other buildings. They pay close attention to them, use what works in their area, and improve upon what does not.

Along with all the categorizing that goes on during the design process, there is a lot of prioritizing that has to be done as well. The relative importance of a room and the things in it can be underscored by size and placement. The most important room in a small house, in both the practical and the symbolic sense, is almost always the great room or its farmhouse kitchen equivalent. To make its importance all the more clear, this area should occupy the largest share of the home and should be prominently located. In a small dwelling, it is generally best to position this space near the home’s center, so that smaller, less significant rooms can be arranged around its periphery as alcoves.

Arranging the rooms and objects in a house according to their relative importance is essential to making any space readable. Presenting such a hierarchy may require that some doorways be enlarged to exaggerate one room’s significance, or that a ceiling be lowered to downplay another’s. As always, necessity will determine these things inasmuch as it is allowed to.

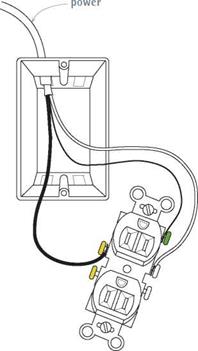

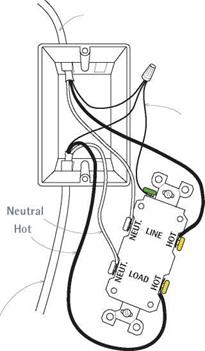

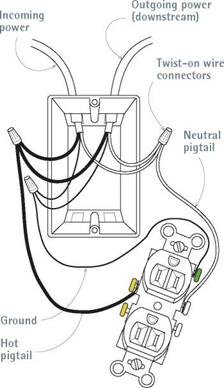

End of circuit. A receptacle at the end of a circuit has only one cable entering the box and none going beyond it. In this case, it’s acceptable to attach wires directly to the receptacle terminals, without using pigtails. Attach the ground wire to the green ground screw, the neutral wire to a silver screw, the hot wire to a gold screw.

End of circuit. A receptacle at the end of a circuit has only one cable entering the box and none going beyond it. In this case, it’s acceptable to attach wires directly to the receptacle terminals, without using pigtails. Attach the ground wire to the green ground screw, the neutral wire to a silver screw, the hot wire to a gold screw.