Curbs and gutters convey rainfall into storm drainage systems, which are discussed in the next section. There are, however, less costly alternatives to the traditional vertical curb and gutter construction.

Following are guidelines for curbs and gutters:

• Substitute grassy swales for curbs and gutters.

• Where curbs are installed, build rolled curbs rather than traditional vertical curbs.

• Reduce the width of concrete gutters or eliminate them entirely.

• Eliminate reverse-flow curbs and gutters in parking lots, or replace them with asphalt curb, header curb, wheel stops, or integral curb/sidewalks.

• With concrete vertical curbs, use extruded construction rather than formwork.

Grassy swales are depressed areas running parallel to the street that serve in lieu of curbs and gutters to convey stormwater. The grading required to construct a swale. can be completed during the grading of the surrounding lots or during final street grading. Therefore, cost savings are approximately equivalent to the cost of installi ng a curb and gutter.

Grassy swales are depressed areas running parallel to the street that serve in lieu of curbs and gutters to convey stormwater. The grading required to construct a swale. can be completed during the grading of the surrounding lots or during final street grading. Therefore, cost savings are approximately equivalent to the cost of installi ng a curb and gutter.

In addition to providing savings in initial construction, swales offer continued savings in the form of lower long-term maintenance. Periodic flushing, replacement, or rehabilitation of pipes is eliminated. Swales within the public right-of-way are typically maintained by the home owner. Most swales can be graded to insure easy mowing.

Where runoff can be accommodated by a shallow swale, the depressions can be carried directly across driveways. Where a deeper depression is required for greater runoff capacity, concrete or metal conduits can be installed under driveways. At street intersec – tiohs, stormwater pipe can be installed under the street.

In addition to providing cost savings, swales allow for local retention of moisture from rainfall and melting snow. This is discussed in greater detail in the next section.

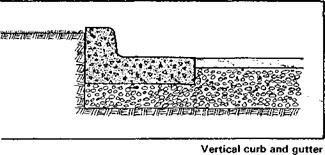

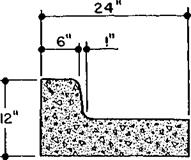

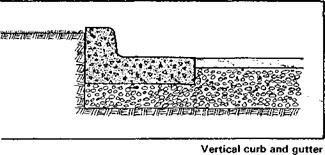

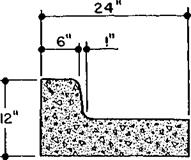

The most common type curb in urban residential settings is the vertical combination curb and gutter.

The most common type curb in urban residential settings is the vertical combination curb and gutter.

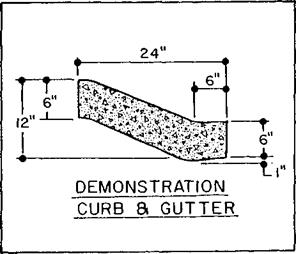

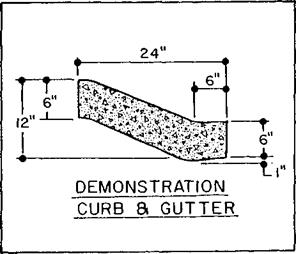

A less costly alternative is the rolled curb, also called the rollover, roll, or mountable curb. Rolled curbs are typically 6 inches or less in height with a plane sloping face or well – rounded corners with a 2-inch to 3- inch radius which allow vehicles to cross them with varying degrees of ease. They can be sized to meet local hydraulic demands; the slope across the face of the gutter and the height of the curb can be designed to meet the projected capacity.

In many instances, curbs are installed before the type of house to be constructed or a lot is selected, and before driveway placement is decided. Therefore, it is usually necessary to remove the vertical curb, install a curb cut for the driveway, and haul away the old curb. With a rolled curb this is not necessary, saving approximately $300 to $450 per housing unit in the affordable housing demonstrations.

However, if vertical curb is chosen, good planning can reduce the added cost of removing any curb. A simple method gaining in popularity is to leave a space for the driveway and pour a separate entrance later. If possible, the driveway entrance should be installed during construction of the adjacent sidewalk to avoid added labor costs.

Concrete gutters, 18 inches to 24 inches wide, are a standard requirement in many development specifications. In most areas, a 12-inch gutter is sufficient, while in more arid regions, gutters can be eliminated entirely by simply extending the asphalt surface to the shoulder or curb. Local weather data should be reviewed, and gutters reduced in size or eliminated where rainfall rates warrant.

Concrete gutters, 18 inches to 24 inches wide, are a standard requirement in many development specifications. In most areas, a 12-inch gutter is sufficient, while in more arid regions, gutters can be eliminated entirely by simply extending the asphalt surface to the shoulder or curb. Local weather data should be reviewed, and gutters reduced in size or eliminated where rainfall rates warrant.

Curbs in Alternatives to vertical curbs in off – Off-Street Parking street parking include:

• elimination of curbs and gutters

• header curbs

• asphalt curb construction

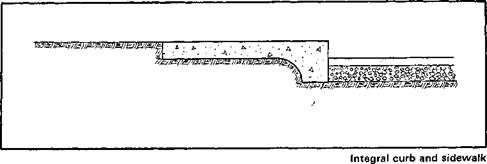

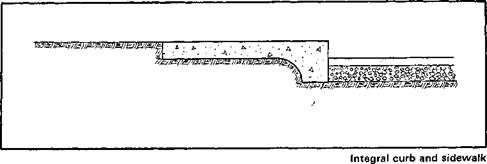

• integral curb and sidewalk

• wheel stops

Combination curb and gutter can be eliminated in many parking lots by encouraging the use of sheet flows.

Much of the curb line in parking areas generally consists of reverse flow gutters – that is, gutters that do not convey water as a conventional gutter does, but simply divert water away from the curb. This can usually be accomplished without a curb by proper grading of the parking lot surface.

Much of the curb line in parking areas generally consists of reverse flow gutters – that is, gutters that do not convey water as a conventional gutter does, but simply divert water away from the curb. This can usually be accomplished without a curb by proper grading of the parking lot surface.

Where curbs are required or chosen, they can often be replaced with header curbs, asphalt curbs, or integral curb and sidewalk, especially in cases where a gutter is not warranted.

Wheel stops are a less expensive alternative to curbs that keep intact the psychological barrier provided by curbs.

Installation of curbs and gutters traditionally required laborintensive formwork and preparation. Such construction methods have increasingly been replaced by extrusion or "slip form" techniques in which the operator, following a string line with a machine, "lays" the concrete out in its final form. This technique can be used to construct either a traditional curb or alternative types of rolled curbs. In areas where traditional formwork is still done, builders should check the availability of labor-saving alternatives.

Installation of curbs and gutters traditionally required laborintensive formwork and preparation. Such construction methods have increasingly been replaced by extrusion or "slip form" techniques in which the operator, following a string line with a machine, "lays" the concrete out in its final form. This technique can be used to construct either a traditional curb or alternative types of rolled curbs. In areas where traditional formwork is still done, builders should check the availability of labor-saving alternatives.

The city permitted construction of rolled curbs as a substitute for 6- inch curbs along the residential streets of the Lakewood Meadows development. A total of 3,720 feet of rolled curb was installed at a cost of $16,740. Traditional vertical curbs were required along one collector street; 1,063 linear feet at a cost of $6,112. The rolled curb saved $1.25 per foot or $146 per housing unit.

The city permitted construction of rolled curbs as a substitute for 6- inch curbs along the residential streets of the Lakewood Meadows development. A total of 3,720 feet of rolled curb was installed at a cost of $16,740. Traditional vertical curbs were required along one collector street; 1,063 linear feet at a cost of $6,112. The rolled curb saved $1.25 per foot or $146 per housing unit.

In Fairway Village, the city permitted substitution of a rolled curb for a 6- inch vertical curb. The rolled curb cost $2,00 per foot less to install. Savings were $10,368 or $477 per unit.

|

Santa Fe curb and gutter vs Fairway Village curb and gutter

|

|

|

CONVENTIONAL CURB a GUTTER

|

|

|

Elkhart County, Indiana

|

Elkhart County approved the elimination of curbs and gutters, and substitution of a system of drainage swales. The cost of typical Elkhart streets, including curbs and gutters, averaged $32 per foot. The curbless demonstration project streets averaged $21 per foot. A total of $330 was saved on each 60-foot wide demonstration lot.

Other affordable housing demonstration projects using rolled curbs instead of the typical vertical curbs include: Tulsa, Oklahoma; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Birmingham, A labarna; White Marsh, Maryland; an d Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Demonstrations in Christian County, Kentucky; Mesa County, Colorado; Greensboro, North Carolina; and Lacey, Washington eliminated curbs and gutters.

|

Toe-nailing or toe-screwing from the top of one horizontal timber, diagonally into the end of the adjacent member. Not quite as rigid as the truss plate

Toe-nailing or toe-screwing from the top of one horizontal timber, diagonally into the end of the adjacent member. Not quite as rigid as the truss plate

Before you can install a new fixture, there’s often an old one to remove. If it’s necessary to shut off water to several fixtures during installation, capping disconnected pipes will allow you to turn the water back on.

Before you can install a new fixture, there’s often an old one to remove. If it’s necessary to shut off water to several fixtures during installation, capping disconnected pipes will allow you to turn the water back on.

Grassy swales are depressed areas running parallel to the street that serve in lieu of curbs and gutters to convey stormwater. The grading required to construct a swale. can be completed during the grading of the surrounding lots or during final street grading. Therefore, cost savings are approximately equivalent to the cost of installi ng a curb and gutter.

Grassy swales are depressed areas running parallel to the street that serve in lieu of curbs and gutters to convey stormwater. The grading required to construct a swale. can be completed during the grading of the surrounding lots or during final street grading. Therefore, cost savings are approximately equivalent to the cost of installi ng a curb and gutter.

The most common type curb in urban residential settings is the vertical combination curb and gutter.

The most common type curb in urban residential settings is the vertical combination curb and gutter.

Much of the curb line in parking areas generally consists of reverse flow gutters – that is, gutters that do not convey water as a conventional gutter does, but simply divert water away from the curb. This can usually be accomplished without a curb by proper grading of the parking lot surface.

Much of the curb line in parking areas generally consists of reverse flow gutters – that is, gutters that do not convey water as a conventional gutter does, but simply divert water away from the curb. This can usually be accomplished without a curb by proper grading of the parking lot surface.

The city permitted construction of rolled curbs as a substitute for 6- inch curbs along the residential streets of the Lakewood Meadows development. A total of 3,720 feet of rolled curb was installed at a cost of $16,740. Traditional vertical curbs were required along one collector street; 1,063 linear feet at a cost of $6,112. The rolled curb saved $1.25 per foot or $146 per housing unit.

The city permitted construction of rolled curbs as a substitute for 6- inch curbs along the residential streets of the Lakewood Meadows development. A total of 3,720 feet of rolled curb was installed at a cost of $16,740. Traditional vertical curbs were required along one collector street; 1,063 linear feet at a cost of $6,112. The rolled curb saved $1.25 per foot or $146 per housing unit.

you see no leaks, allow the water to stand at least overnight or until the inspector signs off on your system.

you see no leaks, allow the water to stand at least overnight or until the inspector signs off on your system.

Guidelines for Shaping an Energy-Efficient House

Guidelines for Shaping an Energy-Efficient House

In hot, arid climates, a house whose long side is 1.3 to 1.6 times the length of its short side offers the best ratio of cool indoor space to exterior wall area.

In hot, arid climates, a house whose long side is 1.3 to 1.6 times the length of its short side offers the best ratio of cool indoor space to exterior wall area.

Study the adjacent topography, trees, and buildings during your initial site inspection. Look for those existing conditions that can block or divert cold winter winds around the building site. Locate the house in these lee – side areas

Study the adjacent topography, trees, and buildings during your initial site inspection. Look for those existing conditions that can block or divert cold winter winds around the building site. Locate the house in these lee – side areas

Use plants and outbuildings to direct prevailing summer breezes into the house and to divert prevailing winter winds away from the house. Once you know the direction of prevailing winter winds, choose a site where topography, vegetation, and other buildings offer protection.

Use plants and outbuildings to direct prevailing summer breezes into the house and to divert prevailing winter winds away from the house. Once you know the direction of prevailing winter winds, choose a site where topography, vegetation, and other buildings offer protection.