Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

The above methods define stiffness as a function of stress alone. Full incorporation of the effects of moisture (as a pressure or suction) should necessitate use of an effective stress framework (see Section 9.5). However a more simple approach, at least in principle, is to adjust the stiffness value calculated by one of the above relationships using a factor that is dependent on the moisture (and, perhaps, other) condition. The AASHTO ‘Mechanistic-Empirical Pavement Design Guide’ (MEPDG) takes this approach, though it’s attention to many details makes the implementation rather complex (ARA, 2004). In this approach, the reference stiffness value, Mropt (the value of Mr at optimum conditions), is adjusted by a factor, Fenv, to allow for different environmental effects, with the value of each factor being computed for each of a range of depths, lateral positions and time increments. For moisture the adjustment factor is based on the equation

Mr

Mr oP^ min

Where km is a material parameter and Sr and Sropt = the actual saturation and the saturation ratio at optimum conditions, respectively. The actual saturation value is obtained from the use of the Soil Water Characteristic Curve (SWCC) see Chapter 2, Section 2.7.1. Other adjustments are included in the Fenv factor to allow for freezing, thawing and temperature. The full approach is too detailed to include here. Interested readers are directed to the relevant report (ARA, 2004).

Long et al. (2006) take another approach, relating modulus to suction and water content rather than to saturation ratio, but still including some stress influence:

(p – 0 ■ 5) + ^t34^ (1 + V)(1 – 2v)

Yh(0.435) (1 – v)

where p is the mean normal stress on the element of soil, 0 and w are the volumetric and gravimetric water contents, respectively, 5 is the matric suction pressure, S0 is the slope of the soil desorptive curve (the rate of change of the logarithm of 5 with the logarithm of 0), Yh is the suction volumetric change index (an indicator of the sensitivity of volume change to change in matric suction) and v is Poisson’s ratio.

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

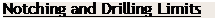

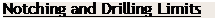

It’s often necessary to notch or drill framing to run supply and waste pipes.

If you comply with code guidelines, given in "Maximum Sizes for Holes and Notches," on p. 287, you’ll avoid weakening the structure. Although that table is based on the following rules of thumb, remember that local building codes have the final say.

Joists

You may drill holes along the entire span of a joist, provided the holes are at least 2 in. from the joist’s edge and don’t exceed one – third of the joist’s depth. Notches are not

allowed in the middle third of a joist span. Otherwise, notches are allowed if they don’t exceed one-sixth of the joist’s depth.

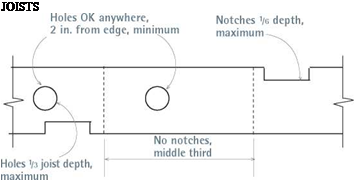

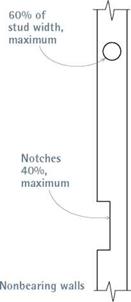

Studs

Drilled holes must be at least 78 in. from the stud’s edge. Ideally, holes should be centered in the stud. If it’s necessary to drill two holes in close proximity, align the holes vertically, rather than drilling them side by side. Individual hole diameters must not exceed 40 percent of the width of a bearing-wall stud, if those studs are doubled and holes don’t pass through more than two adjacent

doubled studs; hole diameters must not exceed 60 percent of the width of nonbearing-wall studs. Notch width may not exceed 25 percent of the width of a bearing – wall stud or 40 percent of the width of a nonbearing-wall stud.

Edge protection

Any pipe or electrical cable less than 11/ in. from a stud edge must be protected by steel nail plates or shoes at least Ум in. thick, to prevent puncture by drywall nails or screws.

Pipe Slope

DWV pipes slope, so before drilling or notching framing, snap sloping chalklines across the stud edges; then angle your drill bits slightly to match that slope. Drill holes 74 in. larger than the outside dimension of the pipe, so the pipe feeds through easily. Nonetheless, if DWV pipe runs are lengthy, you may need to cut pipe into 30-in. sections (slightly shorter than the distance between two 16-in. on-center studs) and join pipe sections with couplings. That is, it may be impossible to feed a single uncut DWV pipe through holes cut in a stud wall.

When hole diameters exceed maximur allowed by code, reinforce framing wi1 a steel stud shoe. When hole diameters exceed maximur allowed by code, reinforce framing wi1 a steel stud shoe.

|

The toilet flange (orange ring) will sit atop the finish floor. So if the finish floor is not yet installed, place scrap under the flange, elevating it to the correct height. This assembly is essentially the same as that shown in “Constricted Spaces," on p. 282.

|

|

|

Support vent stacks in mid-story by using plumber’s strap to tie stacks to blocking between studs.

|

|

Once you’ve secured the closet bend, add pipe sections to the bottom of the bend, back to the takeoff fitting on the main drain that you installed earlier. Maintain a minimum of!4 in. per foot slope, and support drains at least every 4 ft. Dry-fit all pieces, and use a grease pencil to make alignment marks on pipes and fittings.

Other fixture drains. Next run the 1!4-in., 112-in., and 2-in. fixture drains up from the main drain takeoff. Drains must slope at least 14 in. per foot, and all pipe must be rigidly supported every 4 ft. and at each horizontal branch connection. Support pipes with rigid plastic pipe hangers or with plastic-pipe strap, securing pipes to wood blocks beneath them. Support stacks at the base, and in mid-story by strapping or clamping the pipe to a 2x block running between studs.

Run the tub branch drain to the subfloor opening where the tub trap arm will descend.

Pipe stub-outs for lavs and sinks should stick out into living spaces 6 in. or so; you can cut them off or attach trap adapters later. All branch drains end in a sanitary tee. The horizontal leg of the tee receives the trap arm from the fixture, and the upper leg of the tee is the beginning of the branch vent.

Vent runs. Next assemble vent runs, starting with the largest vent—often the 2-in. or 3-in. pipe rising from the combo fitting below the closet bend. Individual branch vents then run to that vent stack, usually joining it in an inverted tee fitting, typically 4 ft. to 5 ft. above the floor. Support all stacks in mid-story with clamps or straps. Horizontal runs of 112-in. branch vents must be at least 42 in. above the floor, or 6 in. above the flood rim of the highest fixture, and those runs typically slope upward at least 14 in. per foot. Continue to build up the vent stack, with as few jogs as possible, until it eventually passes through a flashing unit set in the roof. For code requirements at the roof, see "Vent Termination,” on p. 284.

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

Typical Boise streets have sidewalks on both sides. At Lakewood Meadows, the city permitted elimination of sidewalks on one side of the subdivision’s streets and around T – turnarounds. One higher-order collector street was required to have sidewalks on both sides, but a sidewalk on one side only was allowed for a high-volume arterial street. Walkways were provided in common areas and between T – turnarounds. Typical Boise streets have sidewalks on both sides. At Lakewood Meadows, the city permitted elimination of sidewalks on one side of the subdivision’s streets and around T – turnarounds. One higher-order collector street was required to have sidewalks on both sides, but a sidewalk on one side only was allowed for a high-volume arterial street. Walkways were provided in common areas and between T – turnarounds.

The builder estimated that 2,696 additional linear feet of sidewalk would have been required to comply with existing Boise standards. Construction costs were decreased by $8,088, a per-unit reduction of $216.

Existing Lincoln standards call for 4- foot wide sidewalks on both sides of all residential streets. At Parkside Village, the city permitted Empire Homes to install З-foot wide sidewalks on one side of the street only. Cost savings were $4,289, or $191 per unit.

County standards call for sidewalks on both sides of residential streets. At the Hermitage Hill affordable housing project, this requirement was waived altogether, and no sidewalks were installed. Savings were $40,348, or $558 for each of the 73 units.

Rex Rogers, in Harvard Yard, used an 8-foot concrete swale on one side of the street and graded the street so stormwater was channeled to that side. The swale is only slightly angled and doubles as a sidewalk. Rex Rogers, in Harvard Yard, used an 8-foot concrete swale on one side of the street and graded the street so stormwater was channeled to that side. The swale is only slightly angled and doubles as a sidewalk.

Other demonstration sites which eliminated sidewalks altogether or used them on only one side, contrary to normal local practice, include:

Charlotte, North Carolina; Phoenix, Arizona; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Lacey, Washington; and White Marsh, Maryland.

Pedestrian pathways or meandering walkway systems are used in Phoenix, Arizona and Portland, Oregon.

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

Procedures described in Sec. 6.5.2 are for generating multivariate normal (Gaussian) random variables without imposing constraints or restriction on the values of variates. The procedures under this category are also called unconditional (or nonconditional) simulation (Borgman and Faucette, 1993; Chiles and Delfiner, 1999). In hydrosystems modeling, random variables often exist for which, in addition to their statistical correlation, they are physically related in certain functional forms. In particular, this section describes the procedures for generating multivariate Gaussian random variates that must satisfy prescribed linear relationships. An example is the use of unit hydrograph model for estimating design runoff based on a design rainfall excess hyetograph. The unit hydrograph is applied as follows:

Pu= q (6.38)

where P is an n x J Toeplitz matrix defining the design effective rainfall hyetograph, u is a J x 1 column vector of unit hydrograph ordinates, and q is the n x 1 column vector of direct runoff hydrograph ordinates. In the process of deriving a unit hydrograph for a watershed, there exist various uncertainties rendering u uncertain. Hence the design runoff hydrograph q obtained from Eq. (6.38) is subject to uncertainty. Therefore, to generate a plausible direct runoff hydrograph for a design rainfall excess hyetograph, one could generate unit hydrographs that must consider the following physical constraint:

J

Y^Uj = c (6.39)

j=1

in which c is a constant to ensure that the volume of unit the hydrograph is one unit of effective rainfall.

The linearly constrained Monte Carlo simulation can be conducted by using the acceptance-rejection method first proposed by von Neumann (1951). The AR method generally requires a large number of simulations to satisfy

the constraint and, therefore, is not computationally efficient. Borgman and Faucettee (1993) developed a practical method to convert a Gaussian linearly constrained simulation into a Gaussian conditional simulation that can be implemented straightforwardly. The following discussions will concentrate on the method of Borgman and Faucette (1993).

Conditional simulation (CS) was developed in the field of geostatistics for modeling spatial uncertainty to generate a plausible random field that honors the actual observational values at the sample points (Chiles and Delfiner, 1999). In other words, conditional simulation yields special subsets of realizations from an unconditional simulation in that the generated random variates match with the observations at the sample points. For the multivariate normal case, the Gaussian conditional simulation is to simulate a normal random vector X2 conditional on the normal random vector X1 = x1*. To implement the conditional simulation, define a new random vector X encompassing of Xi and X2 as

generated conditioned on y1 = b. Hence, using the spectral decomposition described in Sec. 6.5.2.2, random vector X subject to linear constraints Eq. (6.42) can be obtained in the following two steps:

1. Calculate (m + K)-dimensional multivariate normal random vector y by unconditional simulation as

У = (yO = VyA-°y5 Z + Ъ (6.45)

where y1 is an m x 1 column vector, y2 is a K x 1 column vector; Vy is an (m + K) x (m + K) eigenvector matrix of Cy, and Лу is a diagonal matrix of eigenvalues of Cy, and Z’ is an (m + K) column vector of independent standard normal variates.

2. Calculate the linearly constrained K-dimensional vector of random variates x, according to Eq. (6.41), as

x = y2* = y2 + C y,12C-,n(b – y1) (6.46)

This constrained multivariate normal simulation has been applied, by considering the uncertainties in the unit hydrograph and geomorphologic instantaneous unit hydrograph, to reliability analysis of hydrosystems engineering infrastructures (Zhao et al., 1997a, 1997b; Wang and Tung, 2005).

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

You may need to cut through joists to accommodate the standard 4 by 3 closet bend beneath a toilet or the drain assembly under a standard tub. In that event, reinforce both ends of severed joists with doubled headers attached with double-joist hangers. This beefed-up framing provides a solid base for the toilet as well.

If joists are exposed, you can also add joists or blocking to optimize support.

Toilets

A minimum 6-in. by 6-in. opening provides enough room to install a no-hub closet bend made of cast iron (41/2 in. outer diameter) or plastic (З1/? in. outer diameter). The center of the toilet drain should be 12 in. from a finish wall or 1232 in. from rough framing. If joists are exposed, add blocking between the joists to stiffen the floor and better support the toilet bowl, even if you don’t need to cut joists to position the bend.

Bathtubs

A 12-in. by 12-in. opening in the subfloor will give you enough room to install the tub’s waste and overflow assembly. Ideally, there should be blocking or a header close to the tub’s drain, that you can pipe-strap it to. To support the fittings that attach to the shower arm and spout stub-outs, add cross-braces between the studs in the end wall. To support tub lips on three sides, attach ledgers to the studs, using galvanized screws or nails. Finally, if there’s access under the tub, add double joists beneath the tub foot.

a sleeve onto each end of the combo. Align the combo takeoff so it is the correct angle to receive the fixture drain you’re adding. Finally, tighten the stainless-steel clamps onto the couplings.

CONNECTING

BRANCH DRAINS AND VENTS

After modifying the framing, assemble branch drains and vents. Here we’ll assume that the new DWV fittings are plastic.

The toilet drain. After framing the tub drain opening, install the 4 by 3 closet bend, centered 12 in. from the finished wall behind the toilet. Install a piece of 2×4 blocking under the closet bend, and end-nailed through the joists on both ends. Use plastic plumber’s tape to secure the bend to the 2×4. What really anchors the closet bend, however, is the closet flange, which is cemented to the closet bend and screwed to the subfloor.

The flange screws to the subfloor yet will sit atop the finish floor when it’s installed. If the finish floor is not in yet, place scrap under the flange so it will be at the correct height. If, on the other hand, the flange is below the finish floor, you can build up the flange by stacking plastic flange extenders till the assembly is level with the floor. Caulk each extender with silicone as you stack it and use long closet bolts to resecure the toilet bowl. (Check with local codes first, because not all allow extenders.)

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

Let’s talk about clearances related to water closets. There’s not a lot to go over, so this can move along quickly. Remember that we are talking about standard plumbing fixtures here, not handicap fixtures. The minimum distance required from the center of a toilet drain to any obstruction on either side is 15 inches. Measuring from the front edge of a toilet to the nearest obstruction must prove a minimum of 18 inches of clear space. When toilets are installed in privacy stalls, you must make sure that the compartments are at least 30 inches wide and at least 60 inches deep. That’s all there is to a typical toilet layout (Fig. 10.7). Let’s talk about clearances related to water closets. There’s not a lot to go over, so this can move along quickly. Remember that we are talking about standard plumbing fixtures here, not handicap fixtures. The minimum distance required from the center of a toilet drain to any obstruction on either side is 15 inches. Measuring from the front edge of a toilet to the nearest obstruction must prove a minimum of 18 inches of clear space. When toilets are installed in privacy stalls, you must make sure that the compartments are at least 30 inches wide and at least 60 inches deep. That’s all there is to a typical toilet layout (Fig. 10.7).

URINALS

urinals must have a minimum distance of 15 inches from the center of the drain to the nearest obstruction on either side. If multiple urinals are mounted side by side, there must be a minimum of 30 inches between the two urinal drains. The required clearance in front of a urinal is 18 inches.

LAVATORIES

Lavatories are not affected by side measurements, unless other types of plumbing fixtures are involved. The minimum distance in front of a lavatory should not be less than 18 inches. Obviously, minimum requirements are just that, minimums. It is best when more space can be dedicated to a bathroom in order to make the fixtures more user-friendly. Lavatories are not affected by side measurements, unless other types of plumbing fixtures are involved. The minimum distance in front of a lavatory should not be less than 18 inches. Obviously, minimum requirements are just that, minimums. It is best when more space can be dedicated to a bathroom in order to make the fixtures more user-friendly.

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

The only types of sign-support systems that should be used are those that have been approved for use by the FHWA. The following concerns should be addressed in the selection of an appropriate single-sign-support system:

• The specifications for support size provided by many states provide information on the maximum sign panel area to be mounted on the support. The shape of the sign as well as the area should be considered when determining the type and number of supports required. For example, a 5-ft X 2-ft (1525-mm X 610-mm) guide sign will have less area than a 4-ft X 4-ft (1220-mm X 1220-mm) warning sign. The wide dimension of the guide sign, however, will result in excessive vibration from wind loads if it is placed on a single sign support without bracing. As a general rule, signs over 40 in (1000 mm) wide should be placed on multiple supports.

• Sign-support systems that are not placed in concrete foundations perform better in strong soils than in weak soils, such as sand. When the system is directly placed in weak soils, an anchor plate, a proper concrete footing, or embedment to a greater depth than used for strong soils may be required. This will hold the post firmly in the ground, preventing rotation due to wind loads, and help ensure proper operation during impact.

• The embedment depth is important for proper sign assembly operation. One-piece sign assemblies will pull out of the ground if not buried sufficiently deep. If buried too deep, it is difficult to remove the buried segment. Similarly, proper embedment depth for assemblies that use an anchor piece is important to prevent damage to the anchor piece on impact and to prevent rotation due to wind loads. The proper embedment depth varies by type of support system.

• Do not use sign-support sizes larger than required to support the sign or larger than approved for single-support types. For example, a slip base assembly should be used rather than a 6-lb/ft (9-kg/m) U-channel post.

• Do not combine supports, such as square tube inside of pipe, or double the supports, such as back-to-back U-channels.

• Do not use diagonal bracing to strengthen a damaged or improperly designed support system.

• Sign-support assemblies are categorized as unidirectional, bidirectional, and multidirectional. Unidirectional supports will function properly only when impacted from one direction, and bidirectional, from two directions. Multidirectional supports will function properly when impacted from any direction.

• The same type of support post can be configured to operate in different ways upon impact. For example, the U-channel post is basically a unidirectional, base-bending support when buried directly in the ground. It can also be spliced to an anchor piece to provide breakaway characteristics or installed with a frangible coupling to provide multidirectional capability.

• Whenever an anchor system design is used, the anchor stub should not extend more than 4 in (100 mm) above the ground. Extensions above the ground more than this can snag the vehicle undercarriage.

• A minimum mounting height of 9 ft (2740 mm) from the ground to the top of the sign panel is recommended for all single-sign-support installations. Mounting the signs at this minimum height will reduce the possibility of windshield penetration by a sign that bends or yields into the vehicle upon impact.

Posted by admin on 20/ 11/ 15

The behaviour of unbound granular materials in a pavement structure is stress – dependent. For that reason the linear elastic model is not very suitable. A non-linear elastic model, with an elastic modulus varying with the stress and strain level is, therefore, needed.

For isotropic materials, moduli depend only on two stress invariants1: the mean stress level, p, and the deviatoric stress, q, which are given in the general, as well as the axi-symmetric case (cylindrical state of stress with o1 = oaxial and o2 = o3 =

oradial as:

General

P = T

q = 2 0ij0ij with 0ij = 0ij pSij

In a similar way strain invariants can be introduced. The volumetric strain ev and the deviatoric strain eq, are defined as:

An invariant has the same value regardless of the orientation at which it is measured.

(9.3)

The stresses and strains are interconnected through the material properties as stated in Eq. 9.1 and the elastic (resilient) response of the material can be expressed according to Hooke’s law as a diagonal matrix:

|

Sv

|

1

|

3 (1 – 2v) 0 2

|

p

|

|

Sq_

|

= E

|

_ 0 – (1 + v)_

|

q

|

where E and v are the material stiffness modulus (or the resilient modulus, usually denoted Mr) and Poisson’s ratio respectively, defined as:

Дq Дє3

Mr or E = and v = – (9.5)

Дє1 Дє1

where Д stands for the incremental change during the loading. An alternative formulation is:

where Kr and Gr are the bulk and shear moduli of the material. The bulk and the shear moduli are connected to the resilient modulus and the Poisson’s ratio through:

for isotropic materials.

The resilient modulus for most unbound pavement materials and soils is stress – dependent but the Poisson’s ratio is not, or at least to a much smaller extent. Biarez (1961) described the stress-dependent stress-strain behaviour of granular materials subjected to repeated loading. Independently, similar work was performed in the United States (Hicks and Monismith, 1971). Both results presented the к-0 model, which is written with dimensionless coefficients like:

3 p k2

Mr = ki pa and v = constant (9.8)

PaJ

where Mr is the resilient modulus, p is the mean stress, pa is the reference pressure (pa = 100 kPa) and k1, k2 are coefficients from a regression analyses usually based on repeated load triaxial test results. This model has been very popular for

describing non-linear resilient response of unbound granular materials. It assumes a constant Poisson’s ratio and that the resilient modulus is independent of the devia – toric stress. To address this latter limitation the Uzan-Witczak model – often called the “Universal” model – has become widely promoted, especially, in recent years, by authors in North America, e. g. Pan et al. (2006). It takes the form:

Mr = kpa 1 + and v = constant (9.9)

Pa PaJ

Subgrade soils are also stress-dependent and can also be modelled by one of the k-0 approaches. The principle difference between granular materials and many soils is that the former exhibit a strain-hardening stiffness whereas the latter, typically, exhibit strain-softening behaviour under transient stress loadings. In practice, the incorporation of non-linearity into the stiffness computations for subgrade soils is often less important than for granular materials as the stress pulses due to traffic loading will be a far smaller part of the full stress experienced by the subgrade than is the case for the unbound granular layer. Thus the error introduced by ignoring subgrade non-linearity will be correspondingly smaller.

In 1980, Boyce presented some basis for subsequent work on the stress-dependent modelling of the resilient response of cyclically loaded unbound granular material. The Boyce model takes into account both the mean stress and the deviatoric stress, with the bulk and shear moduli, K and G, of the material calculated as:

where Ka, Ga, and n are material parameters determined from curve fitting of repeated load triaxial tests results.

Anisotropy of pavement materials is increasingly being recognised as a property that must be modelled if the pavement is to be adequately described (e. g. Seyhan et al., 2005). The Boyce model was modified to include anisotropy in the early 1990’s (Elhannani, 1991; Hornychetal., 1998). Hornych and co-workers ntroduced anisotropy by multiplying the principal vertical stress, cti in the expression of the elastic potential by a coefficient of anisotropy у so that p and q are redefined as follows (c. f. axi-symmetric part of Eq. 9.2):

and the stress-strain relationships are defined as:

Дєq* = 2 (ДЄ1* – Де/) = — and

q 3 1 1 ! 3Gr

Д n*

Дє„ * = Дє1*+ 2Де3* = – .

Kr

Kr and Gr, the bulk and shear moduli, respectively as:

The k— model, Universal model, Boyce model, and the modified Boyce model must be considered in pavement modelling to ensure a valid stress, strain, and deflection evaluation in pavements. When subjected to repeated loading, two types of deformations are exhibited, linear or non-linear elastic (or resilient) and plastic deformations. Models based on non-linear elasticity deal with resilient deformations only. Their biggest disadvantage is that permanent deformations cannot be modelled.

| |

posts. Stretch a chalkline from the ends of the two end beams across the interior beams and snap a line. Cutting the interior beams to length in this manner ensures a straight rim joist in the front.

posts. Stretch a chalkline from the ends of the two end beams across the interior beams and snap a line. Cutting the interior beams to length in this manner ensures a straight rim joist in the front.

When hole diameters exceed maximur allowed by code, reinforce framing wi1 a steel stud shoe.

When hole diameters exceed maximur allowed by code, reinforce framing wi1 a steel stud shoe.

Typical Boise streets have sidewalks on both sides. At Lakewood Meadows, the city permitted elimination of sidewalks on one side of the subdivision’s streets and around T – turnarounds. One higher-order collector street was required to have sidewalks on both sides, but a sidewalk on one side only was allowed for a high-volume arterial street. Walkways were provided in common areas and between T – turnarounds.

Typical Boise streets have sidewalks on both sides. At Lakewood Meadows, the city permitted elimination of sidewalks on one side of the subdivision’s streets and around T – turnarounds. One higher-order collector street was required to have sidewalks on both sides, but a sidewalk on one side only was allowed for a high-volume arterial street. Walkways were provided in common areas and between T – turnarounds.

Let’s talk about clearances related to water closets. There’s not a lot to go over, so this can move along quickly. Remember that we are talking about standard plumbing fixtures here, not handicap fixtures. The minimum distance required from the center of a toilet drain to any obstruction on either side is 15 inches. Measuring from the front edge of a toilet to the nearest obstruction must prove a minimum of 18 inches of clear space. When toilets are installed in privacy stalls, you must make sure that the compartments are at least 30 inches wide and at least 60 inches deep. That’s all there is to a typical toilet layout (Fig. 10.7).

Let’s talk about clearances related to water closets. There’s not a lot to go over, so this can move along quickly. Remember that we are talking about standard plumbing fixtures here, not handicap fixtures. The minimum distance required from the center of a toilet drain to any obstruction on either side is 15 inches. Measuring from the front edge of a toilet to the nearest obstruction must prove a minimum of 18 inches of clear space. When toilets are installed in privacy stalls, you must make sure that the compartments are at least 30 inches wide and at least 60 inches deep. That’s all there is to a typical toilet layout (Fig. 10.7). Lavatories are not affected by side measurements, unless other types of plumbing fixtures are involved. The minimum distance in front of a lavatory should not be less than 18 inches. Obviously, minimum requirements are just that, minimums. It is best when more space can be dedicated to a bathroom in order to make the fixtures more user-friendly.

Lavatories are not affected by side measurements, unless other types of plumbing fixtures are involved. The minimum distance in front of a lavatory should not be less than 18 inches. Obviously, minimum requirements are just that, minimums. It is best when more space can be dedicated to a bathroom in order to make the fixtures more user-friendly.