The transport canals – the magic canal (Lingqu)

In the very same year that the Zhengguo canal came into service, a twelve-year-old child named Zheng ascends to the throne of Qin. Because of all the irrigation works, he soon inherits unprecedented economic power, and he becomes the first emperor.

In 225 BC Zheng uses the Hong canal for the supply of grain to his army, during his gradual advances toward the south.[399] [400] The main grain storage and distribution center becomes established at the junction of this canal and the Yellow River. Later, this virtual nerve center will become the imperial granary.

The victory of Zheng over the Chu ends the warring states period in 221 BC. The conqueror takes the imperial name of Shi Huangdi (or Che Houang-ti). His empire includes, in rough terms, the basins of the middle and lower courses of the Yellow River (Huang) and of the Yangtze.

The emperor, seeking to extend the empire even further to the south and conquer the land of Yue (the region of Canton), plans a fluvial assault using oar-powered military junks fitted with attack towers. In 219 BC, he decides to dig a navigation canal both to transport the army and to carry its provisions.

“… the emperor sent the military commander Tu Sui with a force of men in towered ships to sail south and attack the hundred tribes ofYue, and ordered the supervisor Lu to dig a canal to transport supplies for the men so that they could penetrate deep into the region of Yue.”[401] [402]

However the land is mountainous between the Yangtze and the Xi, the river that flows into the Canton sea. The chosen passage is the Xiang river, a southern tributary of the Yangtze that is connected to it through the grand lake Dongling. The Lingqu canal (magic canal) is therefore opened between the Xiang, flowing toward the north, and the Gui (or Kwei), a tributary of the Xi that flows southerly. The canal follows the course

|

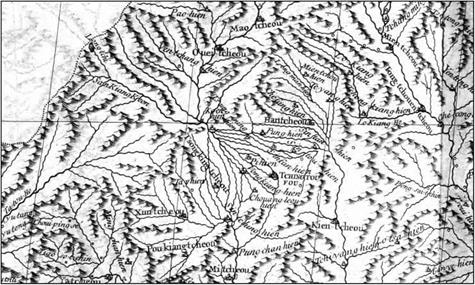

Figure 8.6 The hydraulic works realized by the Qin in south China. The layout of the branched canals in the Chengdu region is taken from the map of von Richthofen (1877). |

of the Li, a minor tributary of the Gui (Figure 8.6).38

An intake on the Xiang River at Xing’an supplies an artificial canal that has an almost horizontal bed, with just enough slope to convey a discharge that is 30% that of the Xiang. This canal flows for about 5 kilometers, to a point near the source of the Li.[403] The Li is channelized to support navigation along some thirty kilometers of its length, as far as the confluence of this small river with the Gui. Alongside the Xiang there is a lateral canal about 3 kilometers long, and with a very modest section: 1 to 2 m deep, and 5 to 8 m wide.

The Xiang intake structure on the Xing’an is obviously inspired by the one built several decades earlier on the Min River. It includes a separation structure downstream of a dam-spillway in the form of a V. This complex is designed to raise the water level to provide for flow into the canal, and to create a basin in which the current is sufficiently weak to allow boats to be maneuvered – while at the same time providing for the evacuation of flood waters into the ancient bed of the Xiang. This 3.9-m high dam is called the Tianping dam. Several other weirs on the canal itself provide for further regulation of the water level as well as for floodwater overflow, as explained in the following 12th century description:

“The passengers who travel (on the canal) are terrified at certain locations for, at about 2 li (1 km) from the intake where the “spade head” divides the water and guides one of the branches toward the canal, there is another weir (literally: structure that lets excess water leave). Without this weir, the violent force of the springtime flow would damage the canal’s support wall, and the water would never get to the south. Thanks to this structure, the violence of the water is calmed, the dike is not broken, and the water in the canal flows gently. [….] This is truly what one can call an ingenious device. The canal waters wind around in the district of Xing’an, and people use it to irrigate their fields.”[404]

|

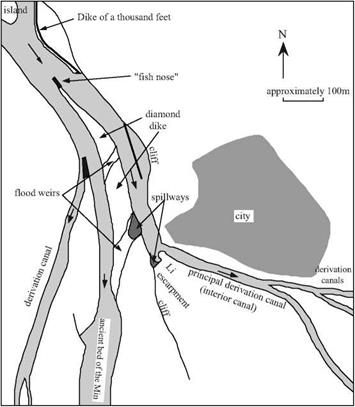

Figure 8.7 The magic canal (Lingqu), communication link between the Yangtze and the Xi (map from Needham, Ling, Gwei-Djen, 1971, detailed plan adapted from Zheng (1991) and Schnitter (1994)). The detail of the installation at the right may not be as it was built under Shi Huangdi, for it underwent important renovations in 825 AD under the Tang. |

Later on another navigable channel is dug behind the separation structure to facilitate the turning of barges and their passage from one canal to the other (Figure 8.7).

The magic canal is renovated in 825 AD and fitted with single gates (flush locks, a system we discuss further on) on the two canals and possibly also on the channelized Li, to maintain navigability during low-water periods. These flush locks are probably replaced in the 12th century by true chamber locks, with 36 openings in all. The canal is destined to remain in service through all of Chinese history, right up to the present. The completion of this project, along with the canals that had already been created during the feudal period, created a continuous watercourse – though indirect – that links Canton to Chang’an through the Xi, the Li, the Xiang, the Yangtze, the Huai, and then the Yellow River and the Wei canal.