Design is a process of continuing revision that doesn’t stop until you have finished architectural drawings, if then. The closer you get to a design that works, the more information you need. Once you have a floor plan that satisfies most of your program requirements, double-check the assumptions underlying your design. Then revisit your local planning department with your proposed floor plan superimposed on your lot and with elevations or a model. Make sure you ask detailed questions about anything that seems unclear.

Remember, the more specific information you bring to the planner, the better feedback you’ll

get. You can save yourself a lot of backtracking if you confirm that officials will allow you to do the renovations as designed and that you can afford to continue. Make sure you understand the approval process. Many communities require design review or other approvals before you can even apply for a building permit. If you will be living in the house while working on it, get a temporary certificate of occupancy (C. O.).

The same principle applies when discussing construction costs with a contractor. Though you may not yet have the working drawings required for a detailed estimate, you’ll have enough to confirm ballpark costs with a reputable contractor. If you have floor plans and elevations or a model, you are about one-third of the way through the design process.

WORKING DRAWINGS

Once you’ve reconsidered layouts in light of the constraints noted above, proceed to working drawings, which should include accurately drawn floor plans and elevations. Details required for these drawings depend on several variables, the most important being how big the job is and who’s doing the work. A conscientious, experienced builder who practices sound construction and knows code requirements can usually intuit what needs doing even if drawings lack occasional details.

In addition, final drawings are essential because (1) the contractor needs them to give you a solid estimate; (2) they help the contractor anticipate problems and suggest changes before scheduling subcontractors; (3) lenders require them; and (4) many municipalities require tight drawings before issuing work permits—that is, in most communities, both planning and building departments review plans.

How detailed should finished drawings be?

As a minimum, building departments require a cross section from foundation to roof so they can see how the building is framed, insulated, sheathed, and finished. Thus if the job is complex—say, a major kitchen remodeling or more than one room—hire an architect to create a set of working drawings. Because construction documents are usually 40 percent to 50 percent of an architect’s total fee, and that fee is customarily 10 percent to 15 percent of total costs, figure that working drawings with floor plans, elevations, and cross sections will be roughly 5 percent of your total budget.

An Overview of Renovation

For handy reference, here’s a step-by-step review of important planning considerations. It begins by reiterating planning steps and then presents a typical sequence for construction.

A PLANNING OVERVIEW

1. Make wish lists, and analyze what works and what doesn’t in the existing house. Keep a renovation notebook. Then consider how well your designs will satisfy your wish list.

2. Measure rooms, noting the location and condition of the structure and utility systems. Map the site, and consider how well exterior design changes fit the neighborhood.

3. Consider physical and financial constraints. Talk to a contractor about renovation costs. Get preliminary approval on financing.

Visit your local planning department.

4. Generate design variations. As favorites emerge, compare them to your wish list and to any constraints. Rework designs until you settle on one.

5. Double-check your design. Revisit the planning department with floor plans and either elevation drawings or a cardboard model.

6. Prepare permit plans and obtain permits. In most communities, the permit process consists of two steps (planning permits and building permits). If you will be living in the house while working on it, get a temporary C. O.

7. Prepare working drawings. List in detail all building components, assemblies, materials, and finishes.

8. Obtain bids from contractors, and select one. The more detail you give bidders, the more realistic and accurate the bids will be.

A RENOVATION SEQUENCE

Be prepared to continue making design decisions as work proceeds. No matter how detailed your plans, you’ll need to make adjustments as you renovate. The order in which you complete tasks also depends on the coordination of subcontractors. Here’s a typical sequence, if such a thing exists.

1. Clean up. Clean out debris and add rough weather-proofing to gaping holes. Organize the site for efficient work flow.

2. Secure the building so you can store materials and, if necessary, live there.

3. Install temporary facilities such as electrical field receptacles and chemical toilets; hook up temporary utilities.

4. Handle major structural work in the basement or crawl space, repairing damage and flaws that could cause further settling. Correct water problems that could threaten the structure.

5. Replace or replumb posts, columns, girders, and joists that have deteriorated.

6. Demolish walls, ceilings, and floors, and remove debris as it accumulates. If you’re not living in the house, install temporary facilities before you start demolition.

7. Do necessary structural carpentry, such as altering load-bearing walls, joists, headers, and collar ties.

8. Attend to the roof as soon as practical.

(But make structural changes first, because they could undermine the integrity of a finished roof.)

9. Install windows, doors, and exteriors.

10. Erect interior partitions, the nonbearing walls not framed earlier.

11. Rough out heating, plumbing, gas, and electrical systems (no fixtures yet). Install insulation.

12. Hang wall and ceiling surfaces such as drywall.

13. Install underlayment for finish floors; apply tile floors.

14. Set plumbing fixtures and radiators for baseboard heat, wire electrical receptacles, and so on.

15. Finish taping drywall.

16.

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

17. Paint and wallpaper. (Some renovators do this after trim is in place.)

18. Repair and replace trim around windows and doors. Hang doors, and finish all interior woodwork.

19. Finish floors.

20. Install final details, such as baseboard trim, interior doors, electrical outlet plates, hardware, and floor registers.

Case Histories

Renovation is rarely an easy road. Even the happy endings can take more time and money than owners thought they had. Renovation also requires the courage to start and then the stamina to stay with it.

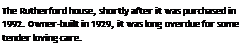

RUTHERFORD HOUSE

The renovators: Martha Rutherford, an educator, loved traveling and collecting indigenous art. Her husband, Dean, a contractor, had lived for six years in Latin America before deciding that the priesthood was not for him.

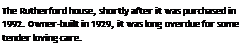

The house: Two-story, owner-built box was erected in 1929. The builder’s widow finally moved on in 1992, after spending most of the previous decade in the living room with four Dobermans, a goat, and a duck. The animals rarely went outside. Dean and Marty stepped carefully into the gloomy interior (the ceiling was painted black), looked at the living room, looked at each other, looked at their real estate agent, and said, "We’ll take it.”

What worked: Location, location, location. Marty is a city gal, Dean a country boy. The wooded site in the Berkeley hills allowed them to live near a major metropolitan area and yet be in the country. But the decision to buy was more mystical than rational.

What didn’t work: The widow had abandoned the bottom floor because it had a year-round stream running through it. The northwest corner of the house was completely gone. The kitchen floor joists were so sodden they were spongy, and the bathroom had rotted out. Between every pair of rafters was a rat’s nest. A beehive blocked the furnace flue. Dean: "I guess the house brought out my seminarian training—you know, salvation and all.”

Constraints:

► Dean had just 3 months to get the house habitable before resuming his construction business full-time.

► The Rutherfords were determined to live within their means, so the renovation would need to stretch over several years.

► Although neighbors were delighted that the property would finally be fixed up, they were wary of the job’s scope and impact.

The plan:

► Stabilize the structure.

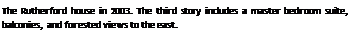

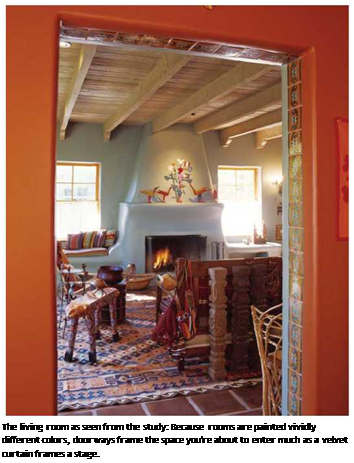

► Add a third story to gain views of the setting and give the house street appeal.

► Open it up: "We wanted a house totally open to the outdoors, with a deck off almost every room."

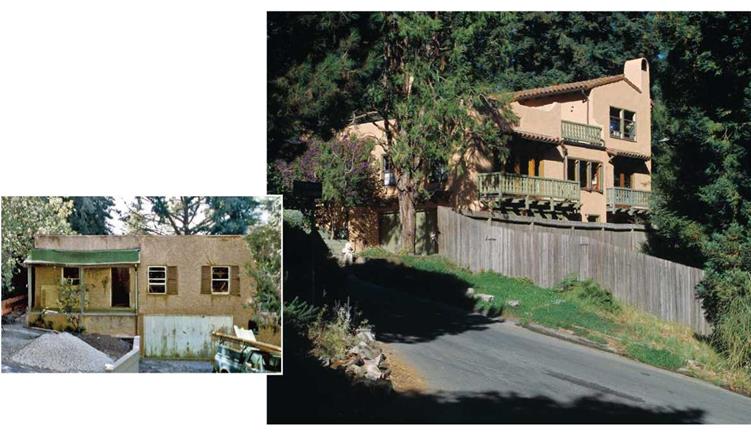

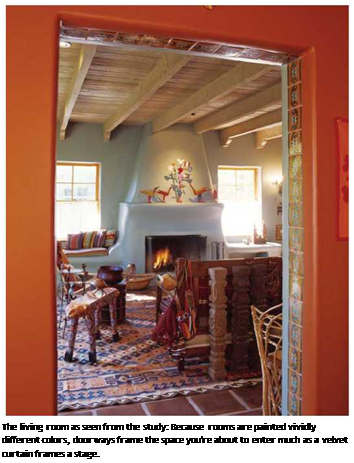

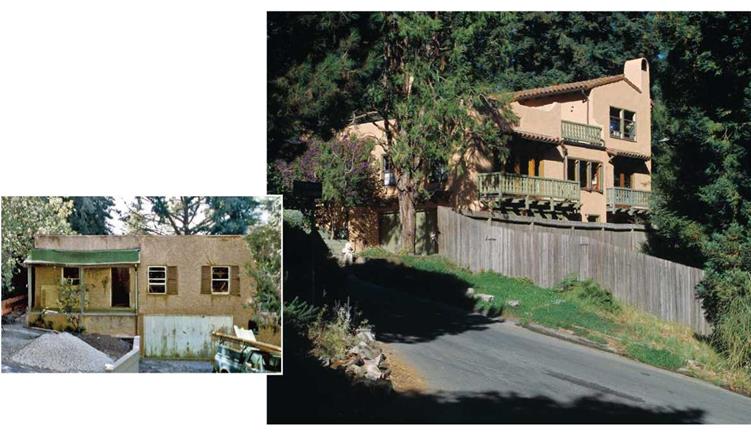

Compromises: Initially, color was a source of conflict. Because her mother had been a painter, Marty grew up surrounded with vibrant colors. Having spent years in monastic settings, Dean had grown up, as he terms it, "in a white world” and feared that Marty’s saturated colors would absorb light and darken the interior, but agreed to them anyway.

Surprises: Because Marty and Dean entered no farther than the living room when they committed to buying the house, the structural problems were a shock. Yet, for Dean the biggest pleasant surprise may have been the colors Marty felt so passionate about. As the two added skylights, opened walls, and installed French doors, they

Posted by admin on 11/ 11/ 15

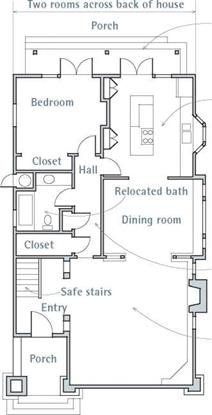

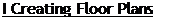

The easiest way to envision change is to draw it. For this, tape tracing paper over the floor plans you drew earlier and start rearranging rooms. Because you drew your floor plans to scale, your overlay drawings will likely be reasonably accurate. If you’re unsure about the dimensions of a room, a fixture, or a piece of furniture, measure again. Also measure the space you’ll need to open and pass through doors, pull chairs away from a The easiest way to envision change is to draw it. For this, tape tracing paper over the floor plans you drew earlier and start rearranging rooms. Because you drew your floor plans to scale, your overlay drawings will likely be reasonably accurate. If you’re unsure about the dimensions of a room, a fixture, or a piece of furniture, measure again. Also measure the space you’ll need to open and pass through doors, pull chairs away from a

|

|

|

|

|

Large kitchen open to backyard

|

|

|

Hall for improved circulation

|

|

|

Enlarged living room open to front yard

|

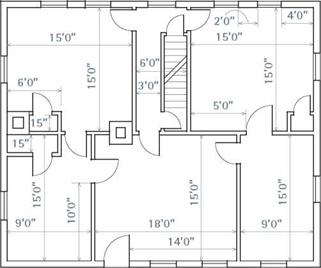

|

FLOOR PLAN: BEFORE FLOOR PLAN: AFTER

The original floor plan presented a pleasant face to the After weighing a number of floor plans, the architect

street, but the back of the house was a hodge-podge of settled on the design that solved the most problems.

doors, dead spaces, and tiny rooms.

table, or remove food from the oven. Have fun, but be realistic: Don’t try to fit too much into a small space.

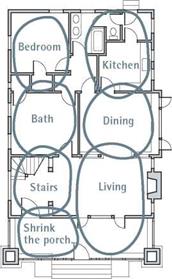

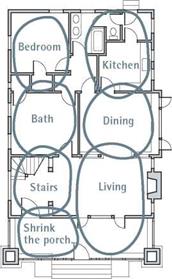

Whether you draw "bubble diagrams” to indicate room usage or arrows to show traffic flow between areas, create optional arrangements, including some you at first might not think you’ll like, for they might suggest possibilities you otherwise might not have considered. Think creatively, "outside the box,” as they say. On paper, it’s easy to move rooms to different locations. Analyze the trade-offs between one floor plan and another. In general, the more problems a design solves, the better. Feel free to borrow features from one plan and graft them onto another. Considering different designs also helps you decide your priorities.

Some layouts will dictate themselves—such as dining rooms next to kitchens with lavatory nearby—but most are fluid and all should be based on common sense. Put bedrooms away from noisy rooms and busy streets, if possible.

When visiting the bathroom in the middle of the night, you shouldn’t need to pass through another bedroom or a public room. Don’t forget to include closets in or near each bedroom, and a closet by the front door.

Design with nature. If your kitchen faces east, you can enjoy morning sun with breakfast. A living room on a westerly wall gives a view of the sunset. North-facing bedrooms will be cooler at night.

Glazing along a south wall can provide a substantial amount of free solar heat in colder months but may require awnings or heat-reducing window films in warmer months. If you live in the Sun Belt, where heat gain is less desirable, try to exploit prevailing breezes and to provide sufficient overhangs along south-facing walls.

In this regard, many states regulate the energy budget for houses and additions by controlling the amount and type of glazing allowed and by requiring energy-performance standards for other building components.

Other ways to look at things. In order to see how your floor plan will translate into a threedimensional structure, either draw elevations or build a model of the existing house with the proposed changes. Until you have drawn elevations or built a model, you can’t be sure your design will work, especially if you are expanding the envelope of the house. Other ways to look at things. In order to see how your floor plan will translate into a threedimensional structure, either draw elevations or build a model of the existing house with the proposed changes. Until you have drawn elevations or built a model, you can’t be sure your design will work, especially if you are expanding the envelope of the house.

If you’re dexterous, make a model of cardboard; most art-supply stores stock the necessary materials. Using a scale of ’/2 in. = 1 ft., draw floor plans and an elevation for each face onto the cardboard, cut them out with a utility knife, tape them together, and install a roof.

Posted by admin on 11/ 11/ 15

Information you’ve gathered thus far will be useful whether you’re hiring a general contractor and an architect or trying to tackle various parts of the job yourself. But before you begin exploring design solutions, consider realities that will have an impact on your plans.

BUDGET CONSTRAINTS

Consult a licensed general contractor (GC) about construction costs, especially before asking an architect to generate a lot of design options, called schematic drawings. An experienced contractor can cite construction costs per square foot in your region but may be reluctant to do so without qualifying those estimates. Such qualifiers will be well founded because every renovation is different, and there’s no way of knowing what surprises a job holds till you open up walls and floors. Most contractors won’t charge for a brief exploratory meeting, they’re courting a client, after all; but if consultations drag on, be prepared to pay consulting time. Fair’s fair.

In this initial meeting, you’re trying to get ballpark figures so you can see if your plans are realistic. Typically a contractor will offer costs per square foot for “vanilla” space such as bedrooms or living rooms as well as for more complicated spaces such as kitchens and bathrooms. Armed with those preliminary numbers, be prepared to modify and trim the scope of your project so you can stay within your budget when you proceed with detailed designs. Try not to proceed with plans you can’t presently afford, unless you are prepared to complete the work in phases, which could mean living with an unfinished renovation, perhaps for years.

CONSTRAINTS FROM PLANNING DEPARTMENTS

Once you’ve mapped the house, but before you sketch any proposed solutions, visit the planning department in your community to learn the ground rules for remodeling. Additions or other expansions of the physical envelope of your house need to be checked against regulations governing setbacks, lot coverage, height limits, parking requirements, and so on. An addition may also be subject to a design review, and you may need to apply for a variance, depending on the scope of the project. A variance may require that you obtain the approval of neighbors. Thus an early visit to local authorities could prevent your falling too deeply in love with a design you won’t be allowed to build.

STYLISTIC CONSTRAINTS

As you renovate, respect what’s already there. Design is tricky stuff to articulate, but a building’s integrity comes from the proportion of its windows to walls, the width and contour of its trim, the slope of its roof—in short, from its parts, just as we humans are distinctive by the color of our hair, the set of our eyes, and the shape of our nose.

Each historical period has its distinctive architectural elements, and generally you’re better off not mixing them. When you must change something, be guided by what’s there. If your house has been modified by earlier owners and you question their judgment, walk around the neighborhood with your camera looking for other houses of the same period. Often, nearby houses will have been built from similar plans or even by the same builder. Here, digital photographs are useful because, once you load them into your computer, you can readily modify them with a software program, such as PhotoShop™.

Posted by admin on 11/ 11/ 15

Renovations beyond cosmetic changes will probably require some alteration of the structure as well as of plumbing, electrical, and heating/ cooling systems. As with many other aspects of renovation, it’s usually best to disturb as little as possible. Until you demolish walls you won’t know the exact location of every last pipe and wire, but by mapping what you can see, you’ll get a sense of where larger, more problematic ducts and pipes are, and thus save time and money by not proceeding with an obviously impractical design.

Now, using the floor plans you drew earlier as templates, create a map for each house system. For each system, use a tracing-paper overlay or mark up a photocopy of the basic floor plan, whichever is more convenient. While you’re examining each room, it’s also smart to note water stains, tired windows, outdated fixtures, ungrounded outlets, sagging floors, and so on. Use the various house assessment lists in Chapter 1 to guide you.

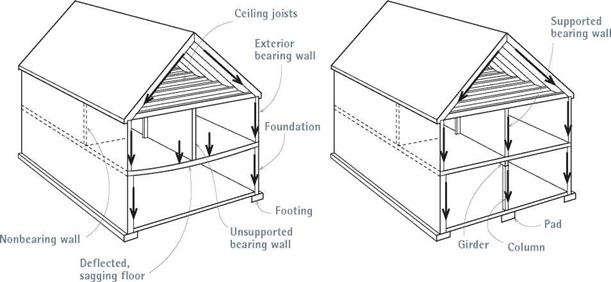

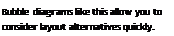

Structural elements should be assessed by a licensed structural engineer, who should also review any design plans that require altering or removing structure. Usually, the big question is whether the walls to be removed are load bearing, and that answer is not always obvious. In addition, in high-wind or earthquake regions, walls may be shear walls, which help a building resist lateral (sideways) forces. Don’t cut or drill into, run pipes through, or remove shear walls until a structural engineer has okayed it.

For the best understanding of your house’s structure, start in the basement, where joists and girders are visible, or in an unfinished attic, where rafters and floor joists are frequently exposed. In finished living spaces, wood floors are usually installed perpendicular to joists, so look at flooring-nail patterns. Common sense can be reliable: If the floor slopes down to the base of a wall, there’s a good chance that wall is bearing a load—and may be insufficiently supported.

In most wood-frame houses, bearing walls run perpendicularly to the joists they support, in effect, shortening the distance those joists must span. Bearing walls are usually supported by bearing walls below, on down to the basement, where they will be supported by a girder and posts. However, there are framing eccentricities, especially for additions.

In apartments and row houses, interior walls often aren’t bearing because most apartments are framed with steel girders, and the floors consist

|

BEFORE AFTER

|

|

of reinforced concrete slabs. In row houses, joists and rafters customarily run the width of the house, between exterior walls. Thus interior walls running parallel to joists or rafters are rarely bearing. Partitions running perpendicularly to framing members were probably not bearing walls originally, but they may have become so if joists were undersize to begin with or if their effective spans were reduced by “remuddlers” cutting into them. In such instances partitions may become bearing walls, and floors may slope toward them.

If a wall is nonbearing, removing it may not cause problems. But if it is bearing, you must first transfer the loads it bears to temporary supports, called shoring, before you can alter it. Similarly, avoid removing any structural buttresses with impunity, such as braces and rafter collar ties. Otherwise unsupported structural elements may sag.

Plumbing fixtures and pipes are usually grouped around a 3-in. or 4-in. soil stack located in a wall near the toilet. Drainpipes are often routed between nearby joists. If the DWV (drainage-waste-vest) system is in decent shape, try not to disturb larger pipes because rerouting them is expensive. Draw fixtures on your plumbing map, and note where main drains emerge in the basement and where vent stacks protrude from the roof.

Supply pipes are rarely a design constraint. That is, because supply pipes are smaller and their water is under pressure, they don’t need to

be pitched, as do waste and drainpipes. In many houses, large vents are concealed within “wet walls” framed out with 2x6s that provide plenty of room for even the biggest pipe. Moreover, drains should slope downward at least!4 in. per foot. Thus a 3-in. drain would need almost an 8 in. height for a 12-ft. horizontal run (3h in. for the exterior diameter of pipe, 3 in. for slope, 1 in. of clearance) and, therefore, would need 2×10 joists, as a minimum. Because cutting 4-in. holes through joists would seriously weaken them, it’s

I Plumbing Map______________

Plumbing fixtures are often grouped around a

3- in. or 4-in. soil stack. Because of their size, the soil stack and the main drain it feeds are the most problematic to relocate.

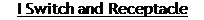

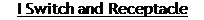

Use these symbols to map your home’s electrical system. Use different-color felt-tip markers to denote different circuits. See p. 234 for more electrical symbols.

easy to see why large drainpipes almost always need to be routed between joists, rather than through them. If the existing joists don’t provide the height needed to run 3-in. or 4-in. drains, it’s possible to build up a platform over an existing floor or to frame out false ceilings below. Yet if such complications present themselves, consider a simpler design.

Heating and cooling systems can also affect design plans, depending on the type of system. The renovator’s primary concern in placing heating and cooling systems is to make sure that pipes and ductwork do not encounter joists, fire-stops, bridging, or other impediments. Modern hydron – ic (hot-water) heating systems are typically fed by %-in. pipe and so can usually be relocated easily; whereas steam heat, supplied by 112-in. to 2-in. pipe, will require planning. By far, forced hot air (FHA) is the most difficult heating system to plan around because the ducts are so bulky. In this case, where space is tight, false walls, floors, and ceilings are commonly employed. But because the hot air is pushed by a fan, ducts do not need to be sloped upward (although this is desirable) to function well. When renovations require the gutting of wall surfaces, vertical duct runs can easily fit between standard 2×4 studs. Flexible insulated duct greatly expands routing options.

Ventilators for bathrooms and appliances are rarely problematic, since exhaust fans draw air from relatively small, isolated areas. By placing

ovens, cooktops, or stoves near exterior walls or beneath a venting bonnet, you can easily route cooking exhaust to the outside.

When mapping a FHA system, note the locations of registers and the furnace. Then intuit the locations of ductwork, using dotted lines to suggest duct runs. In most cases, ducts or hydronic piping will be visible in the basement. For upper-story heat outlets, delivery ducts and pipes generally travel straight up between studs. In general, avoid running ducts within structural walls, because that would require the cutting of wall plates.

Electrical wiring rarely affects design phases unless you intend to move a service panel. Small and flexible, electrical cable is easily routed through walls, floors, and ceilings. Where you don’t want to cut into existing surfaces, or can’t— as with masonry floors—run rigid conduit or track wiring along the surface.

Mapping the electrical system is best done by two people: one standing at the service panel flipping the circuit breakers off and on (or removing fuses from a fused panel), while the other inserts a voltage tester into electrical outlets, as shown in "Using a Voltage Tester,” on p. 235. When the light goes out, you’ve identified the circuit controlling it. (Using cell phones to communicate with each other will save a lot of yelling between floors.) It’s difficult to know exactly where cables are, but by noting where cables enter the panel from floors above and using your map of electrical circuits, you can make an educated guess.

Finally, map electrical safety as best you can (see Chapter 11). In your survey, did you find ungrounded, two-hole receptacles or grounded, three-hole outlets? Is lighting adequate in bathrooms and kitchens? Light switches at the top and bottom of stairs? How about shock protection? Kitchen receptacles within 4 ft. of a sink and all bathroom receptacles must be protected by ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs), which cut off power within f4o second when they detect even a slight leak (4 milliamps to 6 milliamps). Local codes may also specify arc-fault circuit interrupters (AFCIs), which can prevent fires caused by loose or corroded electrical connections, nails puncturing wires, and the like. For more about GFCI and AFCI protection, see Chapter 11.

Posted by admin on 11/ 11/ 15

This section explains how to measure rooms and record the location and condition of the structure and mechanical systems (plumbing, electrical, heating/cooling) as well as how to explore building elements that affect design. Here, too, you learn how to map the site and consider how well exterior renovations will suit the neighborhood.

MEASURING ROOMS

Start by drawing a basic plan of each floor.

Using a 25-ft. retractable tape measure, record the overall dimensions of each room, noting the position of existing doors, windows, closets, fireplaces—anything that affects space. Take the time to record this information accurately. Be consistent in your measurements, always measuring to window and door jambs, not just to casings. (You are really measuring finished openings in walls.) Also note header and sill heights as well as ceiling heights and plane changes. Determine interior and exterior wall thicknesses by measuring door jambs.

To create accurate floor plans, transfer your recorded measurements to graph paper. Graph paper is handy because it helps you draw square corners and maintain scale without needing fancy drafting equipment. As to scale, most people find that Va in. = 1 ft. is large enough for detail and thus doesn’t require graph paper larger than 8’A in. x 11 in. To create accurate floor plans, transfer your recorded measurements to graph paper. Graph paper is handy because it helps you draw square corners and maintain scale without needing fancy drafting equipment. As to scale, most people find that Va in. = 1 ft. is large enough for detail and thus doesn’t require graph paper larger than 8’A in. x 11 in.

MAPPING THE BUILDING SITE

Once you’ve created floor plans, use a 100-ft. tape to measure the overall exterior dimensions. Using graph paper with a smaller scale than you used for the interior drawings (say, f8 in. = 1 ft.), position the house as accurately as you can on the lot. If you don’t know exact lot dimensions, check the closing documents you obtained upon purchasing the house or consult public records.

Also sketch locations of major site features, such as fences, trees, driveways, walks, ponds, streams, gardens, dog runs, and outbuildings. In the margins of the sketch or on separate sheets, draw in or note structures and features on adjacent properties that affect your property or its use—such as a tree you enjoy seeing or a garage you don’t. As you gather information, think about how your proposed renovation might affect your neighbors. If a house addition blocks a neighbor’s view, you might have trouble getting it approved. Likewise, there’s no point in adding a window if it would overlook something ugly.

Most communities have setback requirements, minimum distances from structures to property lines; and seeking variances from setbacks is

often a long, frustrating process. Finally, don’t assume that existing fences accurately represent property lines. Verify property lines early on.

Posted by admin on 11/ 11/ 15

Planning is one of the most satisfying aspects of renovation. On paper, you can live imperially—fruit trees beneath the windows, Italian marble in the bathrooms. When you tire of that, you can remove the tiles and replant the trees… with an eraser. Of course, your finished plans will be a trade-off between what you’d prefer and what you can afford. Yet, during early stages of planning, feel free to let your imagination run wild.

Creating a Home That Suits You

Your house should fit you. In the words of building contractor Dean Rutherford, whose own home is featured near the end of this chapter, "For me, building is about creating a sense of who you are. A place of pause and reflection.

A place where you can be comfortable with yourself.” Indeed, a house should be an expression of who you are, your lifestyle, your loved ones, your dreams. So it’s helpful to begin planning by getting in touch with who you are, which isn’t always easy.

Few homeowners are good at conceptualizing spatially. Still fewer can draw well enough to convey their concepts to an architect. Thus one savvy architect asks his clients to write up a scenario for a happy day in a perfect house. He says it’s surprising how quickly the writing helps people move beyond physical trappings to describing the experiences that make them happy in a home.

For example, some people prefer to wake up slowly while reading in bed or having breakfast on the patio. They may want to putter in a secluded garden or host lavish candlelight dinners. Whatever you wish for.

KEEP A RENOVATION NOTEBOOK KEEP A RENOVATION NOTEBOOK

Much as you’d create a shopping list, jot down house-related thoughts as they occur and file them in a renovation notebook. A notebook is also a convenient place to stash ideas clipped from magazines and newspapers, along with photos you may have shot. If you have kids, encourage their contributions too. At some point, consolidate the notebook ideas and begin creating a wish list of the features you’d like in your renovated home. This list will come in handy when you begin weighing design options.

Architects call items on the wish list program requirements and consider them an essential first step for planning because they establish written criteria against which you can later compare proposed improvements. The list should contain both objective, tangible requirements (such as the number of bedrooms and baths) and subjective, intangible requirements (such as how the house should eventually feet). If you’re presently

living in the house you’ll renovate, you’ll have strong opinions about what inconveniences you’re willing to tolerate and what you’re not. Here are questions to help you get started.

Comfort. Start with your gut feelings. Are the rooms big enough? Ceilings high enough? Do you have enough bedrooms and storage? Enough room to do the things you like? How’s the traffic flow? Do some rooms have two approaches/exits? Or do most feel like dead ends? Must you walk through one bedroom to get to another?

Is the house too drafty? Warm enough? Do rooms receive enough sunlight? Does window screening take advantage of prevailing winds? Can you shut out street noise? Do you feel safe? Can you see who’s on the porch without opening the door? Is the house easy to keep clean? Will your furniture suit your design plans?

Cooking and dining. Do you cook a little or a lot? Do you entertain often? Do you have enough counter space? Are the sink and appliances ideally suited to your cooking preferences? Are counters the right height? Does your kitchen have useful continuous counter space or are the counters interrupted by doors, windows, and foot traffic? Can you reach all shelves? Is storage space sufficient? The refrigerator large enough?

Can you easily transport food to and from dining areas? Can people hang out while you cook? While cooking, do you like to talk on the phone or watch TV? If you recycle cans and bottles, do you have a place to put them?

For recommended minimum cabinet and counter dimensions and common kitchen configurations, see pp. 302 and 303.

Being social. If you plan to entertain, will it be formal or informal? Small card parties with friends or 40-chair club meetings? Is the living room cozy? How about accommodations for overnight guests? Can you escape hubbub when you prefer solitude? That is, when the kids have friends over, do they drive you crazy? (Of course, this may have nothing to do with the house.) Bathrooms. Do you have enough bathrooms, or do jam-ups occur during rush hours? When everyone showers in the morning, do you have enough hot water? Is there a linen closet nearby? Enough cabinet space for sundries?

Do you have tubs and showers where needed? In the tub, can you relax and soak in peace? Is the tub big enough for two? Can you shower without leaving pools of water outside the tub or stall? Is your bathroom presentable for entertaining? Family doings. If you have small children, are surfaces easy to keep clean? Do you have places to store toys? Are other cabinets childproof? Is there an enclosed, outdoor, safe play area? A

room where kids can play on a rainy day? Do you have rooms conducive to reading and homework? Do your kids have enough privacy? And room for their possessions? Will the rooms meet their needs in 5 years? When the kids move out, will your empty nest be too big?

Working at home. If you bring work home or simply work at home, do you have a room that’s adequate for it? Are the walls soundproofed so you can work in peace or work late without disturbing others? Are there enough electrical outlets? How about adequate lighting? Can you shut a door, making your workspace safe from pets and toddlers?

Outer spaces. Do porches protect you from the rain while you’re searching for house keys? Does the yard receive enough sun for a garden? Do you need an outbuilding for lawn equipment and tools? A garage that can double as vehicle shelter and workshop? A spigot near the driveway for car washing? Do you cook out often? Need a fence for privacy or to screen off the neighbors? Need a deck or patio for entertaining outdoors?

| |

Measuring and layout tools: 1, framing square with stair gauges; 2, mason’s string; 3, adjustable square; 4, stud-finder; 5, combination square; 6, adjustable bevel gauge; 7, try square; 8, chalkline box; 9, folding rule with sliding insert;

Measuring and layout tools: 1, framing square with stair gauges; 2, mason’s string; 3, adjustable square; 4, stud-finder; 5, combination square; 6, adjustable bevel gauge; 7, try square; 8, chalkline box; 9, folding rule with sliding insert;

Disconnect electricity. (^) Be sure to cut off the

Disconnect electricity. (^) Be sure to cut off the

Shared thoughts: Marty, on the renovation: "We didn’t rush. We just did things as we could afford them. And in the end, if you take more time, it just doesn’t matter. We do a lot of intuitive things. And every time you go by heart, it works out.”

Shared thoughts: Marty, on the renovation: "We didn’t rush. We just did things as we could afford them. And in the end, if you take more time, it just doesn’t matter. We do a lot of intuitive things. And every time you go by heart, it works out.”

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

Install cabinetwork and countertops.

The easiest way to envision change is to draw it. For this, tape tracing paper over the floor plans you drew earlier and start rearranging rooms. Because you drew your floor plans to scale, your overlay drawings will likely be reasonably accurate. If you’re unsure about the dimensions of a room, a fixture, or a piece of furniture, measure again. Also measure the space you’ll need to open and pass through doors, pull chairs away from a

The easiest way to envision change is to draw it. For this, tape tracing paper over the floor plans you drew earlier and start rearranging rooms. Because you drew your floor plans to scale, your overlay drawings will likely be reasonably accurate. If you’re unsure about the dimensions of a room, a fixture, or a piece of furniture, measure again. Also measure the space you’ll need to open and pass through doors, pull chairs away from a

Other ways to look at things. In order to see how your floor plan will translate into a threedimensional structure, either draw elevations or build a model of the existing house with the proposed changes. Until you have drawn elevations or built a model, you can’t be sure your design will work, especially if you are expanding the envelope of the house.

Other ways to look at things. In order to see how your floor plan will translate into a threedimensional structure, either draw elevations or build a model of the existing house with the proposed changes. Until you have drawn elevations or built a model, you can’t be sure your design will work, especially if you are expanding the envelope of the house.