Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

Steel-pipe posts are frequently used in urban areas and have the advantage of being readily available. They require special fastening hardware, and an earth plate when directly embedded, to prevent the post from rotating from its intended position. Standard steel pipe, schedule 40, galvanized, is readily available from plumbing supply wholesalers. The maximum sign panel areas that can be mounted on the 2-in – and 2.5-ininternal-diameter (51-mm and 64-mm) standard steel pipe are listed in Table 7.6.

Round steel supports, made from standard schedule 40 pipe, that have an internal diameter (ID) of less than 2 in (50 mm) can be embedded directly into the ground to a depth of at least 42 in (1070 mm) and provide acceptable performance upon impact. A steel earth plate measuring 4 in X 12 in X 0.25 in (100 mm X 310 mm X 6 mm) should be welded or bolted to the pipe to prevent support rotation due to the wind.

Standard schedule 40 pipe, 2-in (50-mm) ID and larger, is no longer approved for direct burial installation and must be installed with a weakening device [31]. A breakaway collar assembly is required for standard schedule 40 pipe sizes, equal to or greater than 2-in (50-mm) ID, and also for smaller pipe sizes when the device is likely to be hit. A regular pipe coupling or reducing coupling will provide acceptable breakaway performance. The use of a pipe coupling will, however, frequently result in damage to the anchor piece. Therefore the reducing coupling is the preferred breakaway device. The anchor assembly consists of a concrete footing, usually 30 in (760 mm) deep by 12 in (300 mm) in diameter and a 24-in-long (610-mm) piece of anchor pipe. The anchor pipe is usually one size larger than the signpost to prevent damage to the anchor and to allow use of the reducing coupling. The possibility of damage to the anchor post can be further reduced by embedding the reducing coupling halfway into the concrete footing.

Round steel tube, in wall thicknesses of 12 gauge or less, can be used with anchor systems instead of standard schedule 40 pipe. These tubes are available from a number of manufacturers. Southwestern Pipe Inc. is one tubing manufacturer that also markets the Poz-Loc anchor system. This system consists of a tubular anchor socket with 2.5-in (64-mm) ID and 27 in (686 mm) long constructed of 12 gauge steel. The socket is pointed to facilitate driving into the ground and accepts a 2-in-ID (50-mm) steel round tube as the sign support. The sign support is held in place by driving a post wedge between the socket

TABLE 7.6 Maximum Sign Area for Standard Steel-Pipe Single-Support Posts

a. Area in U. S. Customary units for 70-mi/h wind, ft2

Internal diameter post size, in Maximum sign area, ft2

2.0 6.5

2.5 11.8

b. Area in SI units for 113-km/h wind, m2

Internal diameter post size, mm Maximum sign area, m2

0.6

1.1

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

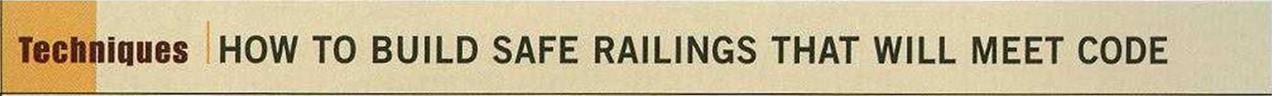

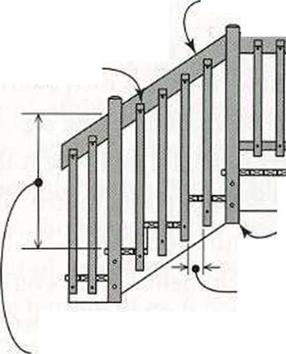

Most codes require railings only when a deck is more than 30 in. off the ground. But you may want to build a rail on a lower deck anyway, for appearance if not for safety. The basic structure of a typical deck or porch railing consists of posts, rails, and balusters, which are also called uprights or pickets.

Even with basic PT lumber, many designs are possible. For example, you can eliminate the bottom rail, extend the balusters down, and fasten them to the rim joist. You can

|

include a 2×6 “cap” installed over the tops of the posts and over the top rail. And you can use a chopsaw to bevel one or both ends of each baluster to give your work a sleeker appearance. There are even decorative FT balusters, along with shaped top and bottom rails that are grooved to hold baluster ends. Also available are quality vinyl railings that are attractive and maintenance-free. As I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, it’s worthwhile to investigate the design possibilities, so take a drive around your neighborhood and visit a lumberyard or home center that carries these building supplies. No matter what the design, make sure the railing meets code requirements (see the sidebar below).

|

|

|

POSTS, RAILS, AND BALUSTERS MUST BE PRECISE. The clean lines on a finished porch or deck depend on accurate railing installation. Here, the posts are notched to fit against the rim joist. The ends of the decking boards overhang beyond the rim joist, even with posts.

[Photo © Larry Haun.]

|

|

|

TO MAKE PORCH RAILINGS and stair handrails both safe and legal, you need to know the basic rules and regulations that dictate how they’re built. The specs below cover most areas of the country, but codes do vary from region to region, so always check with your local building department.

|

|

|

In most regions, any deck higher than 30 in. off the ground needs a railing.

Stairs with more than three risers (three steps) need a handrail.

Stairs that are 44 in. wide or more need a handrail on both sides.

The height of a handrail, measured from the nose front edge of the stair tread, should be between 32 in. and 36 in. The handrail should extend the length of the stairs.

The width of a handrail must be between 1 in. and 2 in. so that it’s easy to grab.

The railing height on a deck guardrail should be between 36 in. and 42 in.

The balusters used on porches and stairs should run vertically, so children can’t climb on them. The spacing between them must be 4 in. or less, so children can’t squeeze through.

The bottom rail must not be more than 4 in. above the deck.

|

|

|

|

Hold balusters down 2 in. so handrail is easy to grasp.

|

|

|

4×4 4 in. from

post deck maximum

4-in. maximum space between balusters

|

|

|

Height of rail must be between 32 in. and 36 in.

|

|

|

Building codes regulate heights of rails and spacing of balusters. Check with your local building department for your area’s requirements.

|

|

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

New concepts have been developed to determine the long term mechanical behaviour of unbound materials under repeated loadings. All these concepts are presented in a special issue (Yu, 2005) of the International Journal of Road Materials and Pavements Design.

The shakedown concept applied to pavements was introduced first by Sharp and Booker (1984). The various possible responses of an elastic-plastic structure to a cyclical load history are indicated schematically in Fig. 9.8. If the load level is sufficiently small, the response is purely elastic, no permanent strains are induced

|

Fig. 9.8 Classical elastic/plastic shakedown behaviour under repeated cyclic tension and compression. Reprinted from Wong et al. (1997), @ 1997, with permission from Elsevier

|

and the structure returns to its original configuration after each load application. However, if the load level exceeds the elastic limit load, permanent plastic strains occur and the response of the structure to a second and subsequent loading cycle is different from the first. When the load exceeds the elastic limit the structure can exhibit three long term responses depending on the load level (Fig. 9.8). After a finite number of load applications, the build up of residual stresses and changing of material properties can be such that the structure’s response is purely elastic, so that no further permanent strain occurs. When this happens, the structure is said to have shaken down: it is in the elastic shakedown region. In a pavement this could mean that some rutting, subsurface deterioration, or cracking occurs but that, after a certain time, this deterioration ceases and no further structural damage occurs.

At still higher load levels however, shakedown does not occur, and either the permanent strains settle into a closed cycle (plastic shakedown behaviour) or they go on, increasing indefinitely (ratcheting behaviour). Contributions of Yu & Hossain (1998), Collins and Boulbibane (2000), Arnold et al. (2003) and Maier et al. (2003) are based on the fact that if either of these latter situations occurs, the structure will fail. The critical load level below which the structure shakes down and above which it fails is called the shakedown load and it is this parameter that is the key design load. The essence of shakedown analysis is to determine the critical shakedown load for a given pavement. Pavements operating above this load are predicted to exhibit increased accumulation of plastic strains under long-term repeated loading conditions that eventually lead to incremental collapse. Those pavements operating at loads below this critical level may exhibit some initial distress, but will eventually settle down to a steady state in which no further mechanical deterioration occurs.

The direct calculation of the shakedown load is difficult. Indeed lower and upper bounds are usually calculated using Melan’s static or Koiter’s kinematic theorems, respectively. These procedures are similar to the familiar limit analysis techniques for failure under monotonic loading, except that now the elastic stress field needs to be known and included in the calculation. Finally, the material is assumed to be perfectly plastic with an associated flow rule.

Shakedown models require an elasticity framework and parameters, for example as provided by the Universal model, and the knowledge of the rupture parameters of the Drucker-Prager or Mohr-Coulomb surfaces. 2D finite element plane strain calculations of pavements have been carried out in this way.

Parameters needed are:

• Elastic behaviour: k1, k2, k3, v; and

• Plastic behaviour: c, y.

Contributions of Habiballah and Chazallon (2005) and Allou et al. (2007) are based on the theory developed by Zarka and Casier (1979) for metallic structures submitted to cyclic loadings. Zarka defines the plastic strains at elastic shakedown with the Melan’s static theorem extended to kinematic hardening materials. The evaluation of the plastic strains when plastic shakedown occurs is based on his simplified method. Habiballah has extended the previous results to unbound granular materials with a non-associated elasto-plastic model. The Drucker-Prager yield surface is used with a von Mise plastic potential.

This approach requires the elasticity parameters of the k — 0 or other model, the rupture line and the law describing the development of the kinematic hardening modulus. This model requires a “multi-stage” procedure, developed by Gidel et al., (2001) which consists, in each permanent deformation test, of performing, successively, several cyclic load sequences, following the same stress path, with the same q/p ratio, but with increasing stress amplitudes. Finite element calculations have been carried out under axi-symmetric condition and 3D. The initial state of stress is determined with the k— 0 or other model, then the plastic strains are calculated.

Parameters required are:

• Elastic behaviour: k1, k2, v (assuming that the k—0 model was selected); and

• Plastic behaviour: c, y, H(p, q).

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

Let’s return to Chris Ryan’s garage to see a method of making girts from a pair of two-by-eights instead of a single eight-by-eight. Chris had seen that Russell Pray used a similar method on the gables ends of the garage at Earthwood and he modified Russell’s method slightly, so that he could use doubled two-by-eights all around the building at the girt level. The advantages were twofold: i) he was able to save on cost, as two two-by-eights are only half as much wood as a single eight – by-eight. And, 2) Chris could install the two-by-eights working alone, whereas hefting long heavy eight-by-eight girts up over the eight-foot-high posts would require a crew of helpers.

This hybrid method of timber framing is very strong. It is not quite traditional timber framing, as it does use some metal fasteners and the joints are easy to make with a circular saw and a chisel. But it requires shaping the top of posts. “Timber framing for the rest of us” does not mean that you have to be afraid of a little timber shaping. I always get a lot of satisfaction when I take the time to make a simple wood joint, even the relatively easy kind described here. Figs. 4.29 through 4.36 will take you through the simple process.

Fig. 4.29: The goal is to support a doubled system of continuous full-sized two – by-eights all around the building at the girt level. One set will be installed flush with the posts on the inside, and the other set will be flush with the posts on the outside. To accomplish this, all that is needed is to remove some of the wood at the top of the post to create a notch — or "shoulder" — upon which the two-byeight will be supported. Here, Chris works on the top of a four-by-eight door frame. He marks a notch eight inches (20.3 centimeters) long and two inches (5.1 centimeters) from each edge of the eight-inch (20.3-centimeter)-wide surface of the post. He cuts as deeply as he can with his circular saw, then turns the timber over and repeats from the other side. Then he makes the transverse cut across the four-inch dimension. This one can be done at the full two-inch depth. Fig. 4.29: The goal is to support a doubled system of continuous full-sized two – by-eights all around the building at the girt level. One set will be installed flush with the posts on the inside, and the other set will be flush with the posts on the outside. To accomplish this, all that is needed is to remove some of the wood at the top of the post to create a notch — or "shoulder" — upon which the two-byeight will be supported. Here, Chris works on the top of a four-by-eight door frame. He marks a notch eight inches (20.3 centimeters) long and two inches (5.1 centimeters) from each edge of the eight-inch (20.3-centimeter)-wide surface of the post. He cuts as deeply as he can with his circular saw, then turns the timber over and repeats from the other side. Then he makes the transverse cut across the four-inch dimension. This one can be done at the full two-inch depth.

Fig. 4.30: The two longer cuts meet, but not quite all the way, because of the circular shape of the saw blade. However, the wood is easily snapped off with a chisel.

Fig. 4.31: The four eight-by-eight corner posts have two inches of wood removed all the way around the top of the post, down to a shoulder eight inches from the top. Again, this is accomplished by combining saw cuts with chisel work. All of the post tops for the garage are shaped in this way before they are stood up and plumbed, but sidewall posts need shoulders on just the inner and outer sides, not all four.

Fig. 4.32: Here, the three major eight-by-eight posts along the sidewall are in place. The middle post is set to the stretched nylon mason’s line. Corner posts are shaped as in the previous picture, Fig. 4.31, and the middle eight-by-eight has had just its sides trimmed back two inches to receive the two-by-eights, butted together on the shoulder.

Fig. 4.33: Two outside two-by-eights, each 14 feet long, meet over the middle post, which is another eight-by-eight. It is the fourth one from the left. The other two posts, with a door lintel notched in near the top, are made of four-by-eights, as shown in Figs. 4.34 and 4.35. This view shows clearly where the inner two-by – eight member of this girt system will bear on the notched posts.

|

Fig. 4.34: This detail shows the notching of the door lintel into the doorposts. The four-inch-thick lintel is set about 1-1/2 inches (3.8 centimeters) into the four-inch dimension of the posts. Four-inch (10.1 – centimeter) screws driven from the side of the post into the lintel could hold it in place, as could four-inch (20-penny) nails. Screws have less impact on the frame than nails, and they are easily removed.

|

Fig. 4.35, far right: This is the other side of Fig. 4.34. Chris used right-angle galvanized metal connectors to hold the lintel fast to the door posts.

Fig. 4.36: The two-by-eights at the gable ends give stability to the entire rectilinear frame of the garage. One of the two-by-eights needs to be attached with a mechanical fastener or toenails. The little piece replaces a chiseled cut from Fig. 4.31 that really did not have to be removed in the first place. If this was an error, it was a very minor one, and gave Chris the option of fastening the doubled two-by-eights in two different ways. Visualization is important in planning even simple joints. Draw everything out on paper first, erasing and redrawing lines

until it makes sense. until it makes sense.

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

An observer of the vast array of Roman technical achievements can only be surprised and disappointed at the lack of technical documentation left by the Romans. With the exception of Vitruvius, whose technical descriptions are sometimes precise (the water mill), and sometimes extremely vague (the aqueducts), there is simply no body of technical literature as we know it. We have extensively cited Frontinus’ book on the aqueducts of Rome, a remarkable work. Yet it is much more of a precise and documented “audit” report than a manual for the guidance of future builders. Pliny’s The Natural History is precious and perhaps an exception, but it has little to do with hydraulic works. It seems that the attitude of the educated Roman leisure class insofar as applied sciences were concerned, tends toward that of the ancient Greeks in retreating from the attitude of the Hellenistic world: the application of knowledge is culturally devalued. Therefore treatises are not written about techniques. It is hard to imagine, for example, such a dearth of technical documentation after the works of Archimedes.

As a consequence, one finds great diversity in the technical solutions found in Roman projects. There are as many exceptionally well conceived works as there are very poorly conceived ones, whether it be in the domain of aqueducts or dams. It is true that in the three largest dams of Spain (Figure 6.29) one sees a certain technical progression, if indeed these dams were built in the order that is thought to be correct. But in the Orient, for example, one finds as many solid and long-lasting retention dams (for example the dams of Homs, and of Harbaqa) as dams whose stability is very problematic, because of an excessive height-to-width ratio.

Another anomaly in the transmission of Roman techniques is visible in the aqueducts that have very large variations of slope from one point to another along their length. The canals in these aqueducts are constructed in anticipation of a constant depth, and yet in steeper segments, the water velocity is greater and, as a consequence, the actual depth of water is less.[295] [296] On the other hand one can see on several aqueducts (at Nimes, for example, but it is not the only one) that, along segments of small slope, the canal walls had to be raised after the initial construction, to prevent overflow. With so many successful projects behind them, how could the Romans not have already experienced this problem and drawn conclusions from it?

Similarly, another problem that has been intriguing to researchers is the Roman evaluation of the discharge of their aqueducts. The quinaria, as we have seen earlier, is a unit of area. It is used by Frontinus as the only reference to determine the quantity of water being delivered. And in Table 6.2 we have, like Frontinus, used a unique equivalence between quinariae and discharges in m3/day. In reality, this equivalence has to be extremely variable. If we consider only several aqueducts of Rome, all having the same slope and the same wall roughness, Table 6.5 shows an important variation, from one aqueduct to the other, of the equivalence between sections (quinariae) and discharges.

|

Table 6.5 Calculation of the discharge of three aqueducts of Rome.92 Variation of discharge corresponding to one quinaria.

|

Aqueduct

|

Canal width (m)

|

Section after Frontinus (quinariae)

|

Water depth calculated from the area (m)

|

Calculated velocity (m/s)

|

Calculated

discharge

(m3/day)

|

Discharge corresponding to 1 quinaria

(m3/day)

|

|

Tepula

|

0.8

|

445

|

0.23

|

0.69

|

11,214

|

25.2

|

|

Juilia

|

0.7

|

1,206

|

0.72

|

0.95

|

41,567

|

34.5

|

|

Anio Novus

|

1

|

4,738

|

1.99

|

1.35

|

232,059

|

49.0

|

|

Were the Romans ignorant of this fact? In reading Frontinus, and in particular the following significant extracts, it would seem that they were not ignorant of it:

“Let us remember that every stream of water, whenever it comes from a higher point and flows into a reservoir after a short run, not only comes up to its measure, but actually yields a surplus; but whenever it comes from a lower point, that is, under less pressure, and is conducted a longer distance, it shrinks in volume, owing to the resistance of its conduit; and that, therefore, on this principle it needs either a check or a help in its discharge.

“But the position of the calix (intake) is also a factor. Placed at right angles and level, it maintains the normal quantity. Set against the current of the water, and sloping downward, it will take in more. If it slopes to one side, so that the water flows by, and if it is inclined with

the current, that is, is less favorably placed for taking in water, it will receive the water slowly and in scant quantity.”[297]

There is both right and wrong in this observation, but in any case there is an intuitive understanding of the importance of the velocity, and even of what hydraulicians today call the ”head”. The importance of the velocity in evaluating the discharge appears even more clearly in this additional extract:

“Whence it appears that the total found by me is none too large. The explanation of this is, that the swifter current of water, coming as it does from a large and rapidly flowing river, increases the volume by its very velocity.”[298]

This intuition as to the importance of the velocity in determining the discharge was not sufficiently strong to be put to use. What has always seemed incomprehensible is the lack of any connection between the knowledge that Frontinus demonstrated – or did not demonstrate – and the work of Heron of Alexandria. We described this work in Chapter 5, and it has long been assumed to have come before Frontinus’ work by at least a century. We now know with certainty that Heron could not have done his writing before 60 AD. Frontinus, while he was studying the aqueducts of Rome, could therefore have been perfectly ignorant of the work of Heron, if indeed that work predated his. It

К

|

Figure 6.39 Remains of the arches of an aqueduct near Rome, between the via Appia Antica and the via Appia Nova (photo by the author).

|

is perhaps even possible that it was after having read Frontinus that Heron was led to write down the correct expression for discharge, as the product of the velocity and the cross-sectional area.

One technology that clearly and uniquely represents Roman know-how is the inverse siphon, such as the one that can be seen in the aqueduct of Gier at Lyon. The number of pipes in each siphon is in effect fixed a priori by the size of the head tank,

and by the number of outlet openings in the downstream wall (Figure 6.13). Lacking valves for control of the discharge of the pressurized pipes, one could compensate for dimensioning errors only by plugging one or several of these openings – an expedient visibly employed for certain siphons of the aqueduct of Gier. If the discharge of the pressurized pipes turns out to be too large, causing emptying of the head tank and consequently a dangerous aspiration of air into the siphon, it is thus possible to reduce the discharge. But one has to wonder what expedients were used when, on the contrary, the capacity of the siphon was insufficient, causing the head tank to overflow.

In assessing the technical contributions of the Romans, one must also remember the

|

Figure 6.40. Aqueduct of Gier for Lyon: seen from the upstream end of the siphon of Yzeron, at the place called “le plat de l’air”. From left to right: hidden behind the trees, the arches that support the canal, the remains of the head tank, and the ramp, the inclined plain that carried the lead pipes descending into the valley to the bridge-siphon (photo by the author).

|

heritage they received from their predecessors, professors and enemies – the Etruscans. The arch, as well as water supply and drainage works, are part of this heritage. We must also not forget to add to the list of Roman shortcomings their inability to maintain the Etruscan systems for land drainage and maintenance built before them in Italy. In their own country, the Romans allowed so many fertile lands to revert back to swamps, soon infested with malaria – for example the famous Pontin marshes. The lazy urbanites of Rome could have produced wheat on these lands, and relieved somewhat the desperate state of the Egyptian peasants.

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

Before sheathing around windows and doors, the trimmers need to be set. Plumb a trimmer on either side of the window with a 2-ft. or 4-ft. level. The top or bottom of the trimmer may need to pull away from the king stud a bit for it to be plumb. Once the level bubble reads plumb, nail the trimmer in place with one 8d toenail on each side, top and bottom.

If the window is 4/0 wide, for example, measure over 4 ft. from the plumb trimmer and make a mark on both the header and rough sill. Pull the trimmer away from this king stud, set it on the 4-ft. marks, and toenail it to the header and to the rough sill with one 8d nail on each side—top and bottom. Measure from corner to corner and side to side to make sure the opening is square and parallel (see p. 87). Do the same for the other window openings.

Setting trimmers for a door takes a bit more time.

I use a 6-ft. level or a short level attached to a straightedge. Place the level against the wide side of a trimmer. A bubble centered in the tube of the level shows if the trimmer is plumb. If it is plumb, you can toenail it to the header and to the bottom plate—one 8d toenail on each side, top and bottom.

|

Hold the level on the 31/г-іп. face of the trimmer and use the hammer’s claws to lever the trimmer away from the king stud until the trimmer rests flush against the level. (Photos by Roe A. Osborn.)

|

If it is not plumb, pull one end out until it is plumb and then nail it in place.

The next step is to straighten the trimmer. Hold the level on the 31/г-іп. face of the trimmer and use the hammer’s claws to lever the trimmer away from the king stud until the trimmer rests flush with the edge of the level (see the left photo below). The 16d nail you drove in the center of the trimmer while framing temporarily holds it straight.

Once you have the trimmer straight, hold it straight by clipping it to the king stud with two 8d nails. Begin by driving an 8d nail partway into either the trimmer or king stud. Bend this nail back onto the other upright. Then drive and bend a second nail over the head of the first (see the right photo below). Install three clips per side. This method eliminates all shims and holds the trimmer true for the life of the building.

To set the second trimmer, measure over from the first. For a prehung door, the measurement is 13A in. more than actual size. The extra width is for a 3A-in. jamb on each side, and the added 1A in. gives you room for adjustment when setting the door frame in place. So for a 32-in.-wide prehung door, measure over 333A in. on both the header and bottom plate and toenail the second trimmer in place. Then straighten and clip it like the first.

|

A simple clip made with two 8ds will hold the trimmer to the king stud.

|

|

Extra studs can be added

|

|

the openings out later with a reciprocating saw. However, before sheathing around these openings, you’ll need to nail in the trimmers (see the sidebar on the facing page). Use scraps of sheathing to fill in any gaps around the windows and doors.

Posted by admin on 21/ 11/ 15

Square steel-tube sign supports are used in many localities. They provide four flat surfaces for mounting sign panels, facing different directions, without special hardware as required by some support types. Square-tube supports can be purchased from a number of manufacturers and are available with %s-in (11-mm) holes or knockouts at 4-in (25-mm) centers on all sides [26, 27, 28]. The square tubing is available in!4-in (6.4-mm) incremental sizes from 1.5 in X 1.5 in (38 mm X 38 mm) to 2.5 in X 2.5 in (64 mm X 64 mm). Maximum sign areas for various square-tube sizes and strengths are illustrated in Table 7.5.

Square tubing can be driven directly into the ground using a drive cap with sledge or power equipment. The performance of the support assembly upon impact, and subsequent repair, are enhanced by using an anchor base. Three common methods of installing a single square-tube sign support are presented in Fig. 7.13. Figure 7.13a shows a direct burial installation. Square tube up to a maximum size of 2.25 in X 2.25 in (57 mm X 57 mm) has been approved for installation by direct burial. The performance of square-tube sign supports upon impact is more predictable, and easier to repair, by the use of an anchor base system [29]. Figure 7.13c shows an anchor base system where a 36-in-long (900-mm) piece of square tube, one size larger than the anchor piece, is driven into the ground. This anchor piece is left protruding 1 to 2 in (25 to 50 mm) above the ground to permit bolting of the signpost. The signpost is inserted 6 to 8 in (150 to 200 mm) into the anchor piece and bolted in place. Figure 7.13b shows a device similar to the anchor base installation except that it uses an outer stiffener sleeve one size larger than the 36-in-long (900-mm) anchor base piece. The stiffener sleeve provides a double-walled thickness that reduces damage to the anchor piece. Upon impact, the post yields at the top of the anchor assembly, normally leaving it undamaged as in Fig. 7.14.

Square steel tubes with perforations on all four sides have been found to provide acceptable crash performance for sizes as large as 2.5 in X 2.5 in (64 mm X 64 mm) when embedded directly into the soil. They are acceptable in both strong and weak soil when embedded to a depth of 48 in (1220 mm). Repairing direct-embedment supports,

|

TABLE 7.5 Maximum Sign Area for Square Steel-Tube Single-Support Posts

|

a. Area in U. S. Customary units for 70-mi/h wind, ft2

|

|

Post size, in*

|

|

Height from ground to center of sign, ft

|

|

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

|

2 X 2 (12 ga)

|

8.4

|

7.0

|

5.9

|

5.0

|

4.3

|

3.6

|

3.1

|

|

2.5 X 2.5 (12 ga)

|

14.8

|

12.5

|

10.7

|

9.2

|

8.0

|

7.0

|

6.1

|

|

2.5 X 2.5 (10 ga)

|

19.0

|

15.3

|

13.1

|

11.4

|

10.0

|

8.8

|

7.7

|

|

b. Area in SI units for 113-km/h wind,

|

mm2

|

|

|

|

|

Height from ground to center of sign, mm

|

|

|

Post size, mm^

|

1830

|

2135

|

2440

|

2745

|

3050

|

3350

|

3360

|

|

51 X 51 (12 ga)

|

0.8

|

0.7

|

0.5

|

0.5

|

0.4

|

0.3

|

0.3

|

|

64 X 64 (12 ga)

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

0.9

|

0.9

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.6

|

|

64 X 64 (10 ga)

|

1.7

|

1.4

|

1.2

|

1.1

|

0.9

|

0.8

|

0.7

|

*Based on 39-kip/in2 minimum yield point steel. fBased on 275-MPa minimum yield point steel.

|

|

FIGURE 7.13 Square-tube sign-support system. (a) Direct burial. (b) Stiffener sleeve anchor. (c) Anchor assembly. Dimensions shown as mm. Conversions: 100 mm = 4 in, 460 mm = 8 in, 900 mm = 36 in.

|

|

FIGURE 7.14 Typical square-tube damage with stiffener sleeve anchor assembly. (a) Prior to impact. (b) Breakaway action. (c) Removal of broken stub. Dimensions shown as mm. 100 mm = 4 in.

|

however, is more difficult than repairing the yielding breakaway system. The V-loc system from Foresight Industries can also be used as an anchor system for square-tube supports.

Figure 7.15 shows anchor systems for square tubing that are manufactured by Unistrut Corporation. Figure 7.15a shows a heavy-duty breakaway anchor for use with 2-in and 2.5-in (50-mm and 64-mm) square tubes. It consists of a /L-in-thick (4.8-mm) wall that eliminates the need for a stiffness sleeve and allows the signpost to break away on impact without damaging the anchor wall. Figure 7.15b shows an anchor post that can be driven directly into extremely hard or rocky soil conditions. It is made

|

FIGURE 7.15 Anchor systems manufactured by Unistrut Corp. (a) Heavy – duty anchor. (b) Anchor post. (c) Stabilization anchor.

|

from 1/4-in X 4-in (6.4-mm X 102-mm) steel angle section that can help stabilize the sign assembly in soil conditions that provide poor resistance to lateral and torsional forces. Figure 7.15c shows a stabilization anchor sleeve that helps adjust for inconsistent roadside gradients. The anchor rods help resist the environmental loads that can cause the signpost to lay over or twist in soft or shoulder dropoff conditions. The stabilization sleeve is installed over an anchor piece and the two rods inserted at a 45° angle to increase stability.

Figure 7.16 presents a soil stabilization anchor manufactured by Xcessories Squared [30]. The stabilizer is attached with a corner bolt, through the lower slots, to an anchor piece of square tube. The tops of the stabilizer piece and anchor are aligned and the

|

FIGURE 7.16 Anchor system manufactured by Xcessories Squared.

|

assembly is driven into the ground until only 2 in (50 mm) remains above the ground surface. After the bottom end of the signpost is inserted 8 in (200 mm) into the anchor assembly, it is secured with a corner bolt from the back side, through the stabilizer, anchor, and signpost.

| |

[Photo © Larry Haun]

[Photo © Larry Haun]

A ten-year design storm is the typical standard for the "minor" stormwater system in a residential development. However, major channels or culverts with large contributing areas require special consideration. Design storm frequency is based on convenience and economics. A community decides how much to pay to insure against the possibility of flooding. The merits of each proposed site plan must be considered, since each site adapts differently to various designs. Performance requirements, which generally encourage innovative and less costly alternatives, should be used over prescription standards.

A ten-year design storm is the typical standard for the "minor" stormwater system in a residential development. However, major channels or culverts with large contributing areas require special consideration. Design storm frequency is based on convenience and economics. A community decides how much to pay to insure against the possibility of flooding. The merits of each proposed site plan must be considered, since each site adapts differently to various designs. Performance requirements, which generally encourage innovative and less costly alternatives, should be used over prescription standards.

Endwalls, commonly installed at the end of a drainage pipe, can also be eliminated. With proper grading at the terminal end of the pipe, a flared end section will provide the needed transition at a much lower cost than an endwall.

Endwalls, commonly installed at the end of a drainage pipe, can also be eliminated. With proper grading at the terminal end of the pipe, a flared end section will provide the needed transition at a much lower cost than an endwall.

Fig. 4.29: The goal is to support a doubled system of continuous full-sized two – by-eights all around the building at the girt level. One set will be installed flush with the posts on the inside, and the other set will be flush with the posts on the outside. To accomplish this, all that is needed is to remove some of the wood at the top of the post to create a notch — or "shoulder" — upon which the two-byeight will be supported. Here, Chris works on the top of a four-by-eight door frame. He marks a notch eight inches (20.3 centimeters) long and two inches (5.1 centimeters) from each edge of the eight-inch (20.3-centimeter)-wide surface of the post. He cuts as deeply as he can with his circular saw, then turns the timber over and repeats from the other side. Then he makes the transverse cut across the four-inch dimension. This one can be done at the full two-inch depth.

Fig. 4.29: The goal is to support a doubled system of continuous full-sized two – by-eights all around the building at the girt level. One set will be installed flush with the posts on the inside, and the other set will be flush with the posts on the outside. To accomplish this, all that is needed is to remove some of the wood at the top of the post to create a notch — or "shoulder" — upon which the two-byeight will be supported. Here, Chris works on the top of a four-by-eight door frame. He marks a notch eight inches (20.3 centimeters) long and two inches (5.1 centimeters) from each edge of the eight-inch (20.3-centimeter)-wide surface of the post. He cuts as deeply as he can with his circular saw, then turns the timber over and repeats from the other side. Then he makes the transverse cut across the four-inch dimension. This one can be done at the full two-inch depth.

until it makes sense.

until it makes sense.