Concept of Specific Area

Let us start with the definition of an aggregate’s specific area. Specific area is defined as the grains’ surface area related to a unit mass, usually given in terms of square centimeter per gram (cm2/g). Fillers are tested in Europe with Blaine’s method* according to EN 196-6 (see Chapter 8). The measured specific area depends on how much the parent material was reduced in size (broken up or crushed). The more the material was milled (crushed), the finer the filler, and the larger its specific area.

An example will serve to illustrate the influence of gradation on specific area size. Let us take two fillers and call them A and B. Let them both pass completely (100%) through a 0.063-mm sieve. Laser analyzer tests reveal significant differences in the material smaller than 0.063 mm. There are 20% and 90% of grains smaller than 0.005 mm in fillers A and B, respectively. This means the filler B has a higher content of very fine grains. What difference does this make? A higher content of finer grains means a substantial increase in their specific area. Because of these large differences in the gradation of the fillers that are less than 0.063 mm, the specific areas of fillers A and B may differ widely—even by two or three times—though, at first sight, a simple screening analysis through the 0.063-mm sieve may not suggest such a distinction.

If a filler makes up 10% of a typical SMA mix (100 kg per 1 metric ton), then the specific area of this ingredient alone amounts to 350 million cm2 or 3500 m2, which is equivalent to the area of a sports field that is 100 m long and 35 m wide. That is quite a lot, isn’t it?

In an SMA mixture, the grains’ surface area should be evenly covered with a binder film (a couple of microns thick or a bit more). Different specific areas of filler require different quantities of binder to coat them, which means a changeable demand for binder in a mortar. If the true sieve analysis of a filler passes unnoticed and only a simplified screening through the limit sieve is observed (as with fillers A and B), one should not wonder why the same SMA mixture behaves utterly differently when fillers are changed. The specific area that needs to be coated with binder may be substantially different in one case versus another, and a correction of the added binder content may be necessary.

An increase in the specific area of filler requires an increase in the binder quantity just to preserve a suitable mortar consistency. However, an increase in the filler content with a constant binder content causes a reduction of the film-thickness coating the filler grains, making the mix appear to be drier. A substantial increase in the filler-binder (F:B) index increases the risk of cracking. [12]

We can see that the concept of binder content in a mixture based on the specific area size is pretty vivid and appealing to the imagination. There are some analytic formulae approximating the required binder content related to the specific area of a mineral mix; one can find an example in The Asphalt Handbook (MS-4).

Before we leave the issue of filler gradation and specific area, it should be noted that much research has raised questions about a direct relationship existing between the gradation and the stiffening properties of a filler (e. g., Anderson, 1987). Also, the significance of the amount of material passing the 0.02-mm sieve and its specific area are questioned as they do not appear to influence mortar properties (Brown and Cooley, 1999). Thus it is time to proceed to another concept, that of voids in a dry – compacted filler.

^ Wall sections to show the “guts” of the floors, walls, or ceilings. Think of a wall section drawing as an apple that’s been sliced in half to reveal its core (see the illustration at left). Both section and detail plans (sec below) are sometimes drawn at a larger scale to better identify the details that wouldn’t show up as clearly in a smaller scale.

^ Wall sections to show the “guts” of the floors, walls, or ceilings. Think of a wall section drawing as an apple that’s been sliced in half to reveal its core (see the illustration at left). Both section and detail plans (sec below) are sometimes drawn at a larger scale to better identify the details that wouldn’t show up as clearly in a smaller scale.

A plot plan lets you see, from above, the size of the lot and where your house will be placed on the land. It also shows where utilities like water and electricity are located.

A plot plan lets you see, from above, the size of the lot and where your house will be placed on the land. It also shows where utilities like water and electricity are located.

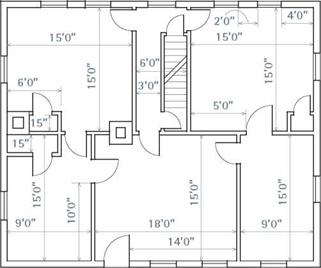

This is the floor plan for a simple four bedroom house. With it you can see the size of the building, the arrangement of the living spaces, and the location of doors and windows.

This is the floor plan for a simple four bedroom house. With it you can see the size of the building, the arrangement of the living spaces, and the location of doors and windows.