WALLS

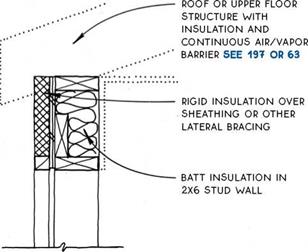

Rigid insulation, with a potential R-value approximately double that of batt insulation, is a very attractive alternative for upgrading the thermal performance of walls. The material is easy to install in large lightweight sheets, has sufficient strength to support most siding and interior finish materials, and can double as an air/ vapor barrier in some cases. Its disadvantages are high cost and potential for toxic offgassing in a fire.

Rigid insulation is most effective when used on the exterior of the building because it covers the entire skin of the building continuously without the interruption of floors or interior partitions. It can act as the backing for siding but does not provide the strength to act as structural sheathing. Alternative methods of bracing the building, such as structural sheathing (see 78A) or let-in bracing (see 77B & C), must therefore be used. Hybrid systems, in which structural sheathing is used only at necessary locations with rigid insulation elsewhere, can also provide cost effective insulation upgrades.

When applied to the exterior of buildings in cold climates, the low permeability of rigid insulation can trap vapor in the stud cavities, causing structural damage. The reverse can be true in warm climates. It is there-

|

FURRING SAME THICKNESS AS RIGID INSULATION AT WINDOW & DOOR OPENINGS AND AS REQUIRED FOR NAILING OF Siding

|

|

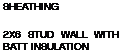

vapor retarder

LOcATED AT INTERIOR

face of 2×6 stud wall

|

|

floor structure with insulation and continuous AIR/vAPOR BARRIER SEE 61-62

|

|

RIGID INSuLATION may Be

continuous over wall or foundation below

|

practicality of specific types of insulation with local professionals.

Used on the interior of a building in a cold climate, rigid insulation can perform three functions at once: insulation, vapor retarder, and air barrier. To accomplish this, a foil-faced insulation board carefully taped at all seams and caulked and/or gasketed at top, bottom, and openings would be used.

fore advisable to carefully coordinate the use of rigid insulation with a high-permeability vapor retarder based on the specific climatic zone and to verify the

The use of interior rigid insulation requires deep electrical boxes and the need for extra-wide backing at corners and at the top plate.

@ RIGID INSULATION

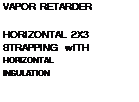

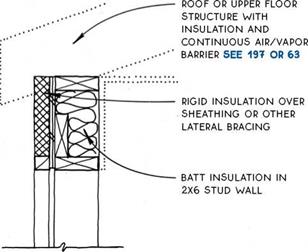

roof or upper floor structure with insulation and continuous air/vapor barrier see 197 QR 63

single 2X6 top plate

single 2X6 top plate

structural sheathing or other bracing batt insulation in 2X6 stud WALL

STRAPPING for NAILING around openings

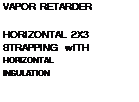

horizontal 2X3 STRAPPING AT 24 IN. o. c. NAILED To studs horizontal batt insulation between

STRAPPING vapor retarder located at interior face of 2X6 stud WALL

WIRING AND PLuMBING

located within

STRAPPING LAYER

Strapping consists of horizontal nailing strips attached to the inside of a stud wall. The strapping touches the studs only at the intersection between the two, so thermal bridging is virtually eliminated. Strapping is used extensively in energy-efficient buildings. With 2×6 studs and 2×3 strapping, an R-25 value can be achieved.

The advantages of the system are that it is simple and straightforward and uses a minimal amount of extra framing materials. With two-thirds of the insula – tive value in the (2×6) stud cavities, an air/vapor barrier can be located at the inside face of the framed wall, thus eliminating the need to puncture it with services. In addition, the plumbing and electrical work itself is simplified by the creation of horizontal chases on the walls.

Strapping must be fastened securely to the studs to prevent rotation, but interior finish panels will ultimately tie the strapping together to keep it in place.

double strapping for

BASE TRIM NAILING floor structure WITH insulation and continuous air/vapor BARRIER SEE 61-62

Extra strapping is usually required for nailing at corners, at window and door openings, and at the base of the wall (see drawing above). In addition, vertical blocks are required for the attachment of electrical boxes.

Strapping may also be applied to the exterior of a building. In this case, the strapping is more easily installed, but the advantage of a horizontal chase interior of the vapor retarder is lost. Furthermore, the strapping insulation must be installed from the exterior, exposed to the weather.

|

SHEATHING

2X4 STUDS AT 24 IN. O. C. WITH BATT INSULATION AND ALIGNED WITH OUTER EDGE OF PLATE

|

|

2X4 studs AT 24 IN. o. c.

with batt insulation aligned with inner edge of plate & offset from outer studs

|

|

vapor retarder

2×8 or 2×10 PLATE

|

Staggered-stud framing is essentially a double stud wall framed on a single wide plate with the studs offset from one another so that there is negligible thermal bridging. The system is appreciated by builders for its minimal deviation from standard frame construction. Staggered-stud framing is substantially the same as platform framing, and subcontractors are sequenced in the same order as standard construction. With this technique, insulative values of R-.30 or more can be attained. A 2×8 or 2×10 plate with staggered 2×4 studs at 24 in. o. c. is most common.

Because there are effectively two separate walls, this system offers a special opportunity at windows and doors to splay the opening.

roof or upper floor structure with insulation and continuous air/vapor BARRIER see 197 QR 63

|

plywood gusset ties stud walls at openings

|

|

STAGGERED 2X4 STuD WALLS FILLED WITH BATT

insulation

|

|

vapor RETARDER located at interior

FACE oF INNER FRAMED WALL

SINGLE 2X SoLE PLATE

|

|

floor structure with insulation and continuous air/vapor BARRIER SEE 61-62

|

By increasing the rough-opening size at the “inner wall,” the opening will be more generous from the inside and reflect light better into the room.

The disadvantages of the system also stem from its similarity to standard platform frame construction. Unlike strapping systems or double wall systems, stag – gered-stud systems have the air/vapor barrier located on the inside (warm) face of the wall, with the attendant problems of sealing perforations of the barrier from plumbing and electrical services.

Double wall framing is capable of achieving the highest insulation values of all the upgraded framing techniques. Values of R-40 are common. Slightly more framing materials and considerably more labor (than strapping or staggered stud) are required for the increased performance.

The outer framed wall is most commonly used as the bearing wall. This strategy has two advantages: The insulation and the inner wall can be installed under the roof out of the weather, and the shear walls are most easily installed and logically located at this (outer wall) location. However, finish detailing at the wall/ceiling joint is complicated if the inner wall is nonstructural, and the continuity of the air/vapor barrier is somewhat

S3

S3

difficult to achieve at the wall/floor intersection.

can be located within the inner wall without having to

Less common (and not illustrated) is the use of the

penetrate the barrier. To get the air/vapor barrier into

inner wall as the bearing wall. This system avoids the minor disadvantage of the outer bearing wall system, but has two major disadvantages: it requires support of the outer wall beyond the edge of the foundation and the outer wall and the extra insulation must be installed from the outside of the building, exposed to the weather.

The ability to locate an air/vapor barrier at the out-

side surface of the inner wall contributes significantly to

this position is simple with an interior bearing wall, but somewhat involved with an exterior bearing wall. It can be accomplished, however, by fastening the barrier to the (outer face of the) inner wall before it is tipped into place. The cavity can be filled with horizontal batts tied to the exterior wall before the inner wall is positioned or insulation can be blown in afterward through holes predrilled in the top plywood gusset.

@ DOUBLE WALL FRAMING

![]()

On a sloping site, it’s often better to build a multilevel deck that follows

On a sloping site, it’s often better to build a multilevel deck that follows waste. Take advantage of standard lumber lengths when determining the size of a deck. For example, a deck that’s 5 ft. 11 in. wide can be framed with 12-ft.-long joists or beams. A deck that’s 61/2 ft. wide would waste В/г ft. of an 8-ft. beam or joist.

waste. Take advantage of standard lumber lengths when determining the size of a deck. For example, a deck that’s 5 ft. 11 in. wide can be framed with 12-ft.-long joists or beams. A deck that’s 61/2 ft. wide would waste В/г ft. of an 8-ft. beam or joist.

the natural contour of the land instead of a single-level deck that requires tall support posts. Houses built on a concrete slab can have a smaller slab poured to create a porch or patio area. Just make sure the slab is 1 in. or so below the floor slab to keep water from entering the house. To promote drainage, pour the slab with a slight slope, about ‘/4 in. per ft. Don’t forget to thicken the concrete and install a metal post base where the posts will be installed to hold the supporting roof beams.

the natural contour of the land instead of a single-level deck that requires tall support posts. Houses built on a concrete slab can have a smaller slab poured to create a porch or patio area. Just make sure the slab is 1 in. or so below the floor slab to keep water from entering the house. To promote drainage, pour the slab with a slight slope, about ‘/4 in. per ft. Don’t forget to thicken the concrete and install a metal post base where the posts will be installed to hold the supporting roof beams.![]()

Framing connectors are worth checking out. If you haven’t discovered the vast variety of framing connectors that are available, try to do so before building a porch or a deck. A well-stocked lumberyard or building supplier will sell connecting hardware designed to reinforce all kinds of joints among different framing members.

Framing connectors are worth checking out. If you haven’t discovered the vast variety of framing connectors that are available, try to do so before building a porch or a deck. A well-stocked lumberyard or building supplier will sell connecting hardware designed to reinforce all kinds of joints among different framing members.

Normally, shear panels aren’t the final, or finish, wall covering, so they don’t have to be installed perfectly. Once these rough panels are nailed in place and inspected by the building department, they’ll be covered with stucco, finish plywood panels, shingles, clapboards, or even metal or vinyl siding. Before sheathing any wall, exterior or interior, check the plans to see what is required. Often, shear panels need to be longer than the standard 8 ft. so they can extend from the pressure-treated foundation sill, across the rim joist and wall studs, and nail into the plates at the top of the wall. This type of construction ties the entire frame together and gives the house added structural stability.

Normally, shear panels aren’t the final, or finish, wall covering, so they don’t have to be installed perfectly. Once these rough panels are nailed in place and inspected by the building department, they’ll be covered with stucco, finish plywood panels, shingles, clapboards, or even metal or vinyl siding. Before sheathing any wall, exterior or interior, check the plans to see what is required. Often, shear panels need to be longer than the standard 8 ft. so they can extend from the pressure-treated foundation sill, across the rim joist and wall studs, and nail into the plates at the top of the wall. This type of construction ties the entire frame together and gives the house added structural stability.

single 2X6 top plate

single 2X6 top plate