■ BY JEFFERSON KOLLE

n the bill from her gas company, Leslie MacKensie of Minneapolis learned that she could have a free energy audit performed on her house, so she made an appointment. After assessing the 1915 bungalow, the auditors showed her air leaks and other problems that resulted in a monthly bill of $110. The auditors left her with weatherstripping and foam-insulation pads to install, along with a list of other needed improvements.

Chipping away at the list has had dramatic results. Even after she expanded her home with a small addition, her current gas bill averages only $80 a month. "Almost as important," she says, "is that now our home is really comfortable to live in all year round."

Home-energy auditing—the process of diagnosing and recommending improvements to reduce a house’s energy consump – tion—is not a new idea, but the reasons to get an audit are more pressing as concerns about costs, comfort, personal health, and the environment loom large.

Along with free or reduced-cost audits offered by utility companies, an increasing number of private companies perform

audits. And while an old leaky house might be the obvious choice for an energy-waste diagnosis, new houses can benefit, too. The results can be an excellent marketing tool for builders and can help homebuyers qualify for an energy-efficient mortgage, which uses energy-cost savings to lower debt-to-income ratios.

The most important thing to note about energy audits, however, is that they don’t save money or energy. Implementing the recommended improvements is how the savings happen.

There Are Two Types of Audits

Energy audits vary in complexity from an unscientific but learned assessment to one that uses an assortment of diagnostic equipment to measure the performance of a house and its systems. The unscientific assessment typically consists of a thorough two- to three-hour walk-through, during which the auditor makes a visual inspection; takes photographs; and records information about the

size of the building and specifics about the assumed efficiencies of the insulation, the appliances, and the HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) system. (For instance, he might know how fiberglass batts should be performing but can’t tell if they were installed properly.)

The scientific approach, which takes four to six hours to complete, uses diagnostic equipment to record and quantify a home’s energy shortcomings. The auditor completes a walk-through of the house, but he doesn’t stop there.

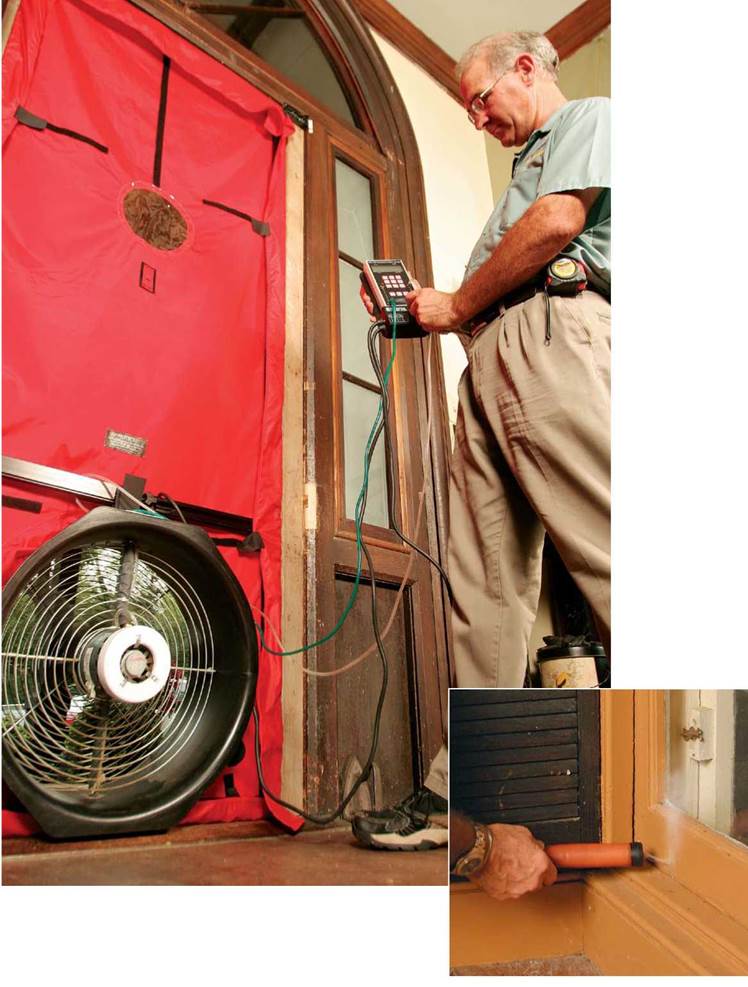

The first step is often a blower-door test. After closing windows, exterior doors, and often flues, the auditor turns on a calibrated fan mounted in an airtight frame temporarily set in an exterior door (see the photo on p. 5). The fan reduces air pressure inside the building, pulling air in through all the holes in the building envelope. Depending on the blower door’s supporting software, the auditor quantifies the number of air changes the house goes through in an hour (expressed as ACH) as well as the combined size of all the air leaks. In an old house, those leaks can

easily equate to leaving the bottom sash of a double-hung window open all year long.

To pinpoint where air infiltration is happening, the auditor holds a smoke stick or smoke pen in front of doors, windows, or other suspect areas (see the inset photo on p. 5). The pen emits a chemical smoke that wafts away from the leak and toward the fan to identify air infiltration. The auditor makes a note of the location and later suggests how to seal the leak.

A blower-door test can find air leaks in heating and cooling ductwork that runs through unconditioned spaces, such as an attic or a crawlspace. But it can’t find leaks in ducts that run through the conditioned space, such as walls and floors. A tool made specifically for that job is a calibrated airflow-measurement device called a duct blaster. After turning off the blower door and taping over the floor, wall, and ceiling registers, the auditor connects the blaster to a central return in the system and measures its airtightness. Leaky ductwork can lead to substantial energy loss, which can be espe-

Making the improvements.

Sealing leaky windows and air ducts, and adding insulation are the most common improvements auditors suggest. Attics can be the largest culprits for air and energy loss.

Sealing leaky windows and air ducts, and adding insulation are the most common improvements auditors suggest. Attics can be the largest culprits for air and energy loss.

dally costly when that loss is happening in an unconditioned space.

Perhaps the best qualitative scientific tool an inspector pulls out during a diagnostic audit is an infrared thermograph, a camera – style device that shows the relative temperatures of objects portrayed as a kaleidoscopic image (see the photos at right). The colors reveal heat loss or gain, which indicates if a wall or attic floor is insulated, for example, and how well that insulation is performing.

It also can identify moisture problems and leaky pipes behind the walls.

The auditor might also use a combustion analyzer and flue-gas monitor to measure the efficiency of boilers and furnaces (see the left photo on p. 8). Finally, he plugs in an electricity-usage monitor near appliances like the refrigerator to determine their efficiency.

Proponents of these diagnostic audits say that scientific measuring allows individual house components to be assessed as part of a whole system in which change to one part affects another. For instance, extensive airsealing could make the building too tight and result in a furnace’s flue gases being sucked down a chimney and into the living space—something that might not be detected without testing. This system’s approach might also show that increasing insulation levels would allow a home to be heated by a smaller boiler. Test equipment can measure these kinds of occurrences, whereas a strictly visual inspection results only in an educated guess. The other main reason to use testing equipment is that retesting can determine the success of the recommended improvements.

Steve Luxton, regional manager for CMC Energy Services® (www. cmcenergy. com), disagrees with the need for scientific testing. Luxton’s company has trained more than 1,000 energy auditors, 90% of whom are working as home inspectors, the folks that mortgage companies require you to hire before they’ll lend you money. "These guys already know what to look for in a house,"

says Luxton. "[They] don’t need a fan to tell you where the leaks are."

His point is well taken; most experts agree that air infiltration is the No. 1 cause of energy loss in any house. Most buildings have common air-infiltration areas that are easy to spot if you know where to look.

[Photo © Larry Haun]

[Photo © Larry Haun]

Remember, you’re going to live in this neighborhood. There’s no time like the present to be friendly and to get to know your neighbors. If you’re building in a remote area, you’ll probably need a generator to get electricity to the site. I’ve built many houses using a portable, gas-powered generator. Make sure your generator is capable of supplying power to several tools at once.

Remember, you’re going to live in this neighborhood. There’s no time like the present to be friendly and to get to know your neighbors. If you’re building in a remote area, you’ll probably need a generator to get electricity to the site. I’ve built many houses using a portable, gas-powered generator. Make sure your generator is capable of supplying power to several tools at once.

Sealing leaky windows and air ducts, and adding insulation are the most common improvements auditors suggest. Attics can be the largest culprits for air and energy loss.

Sealing leaky windows and air ducts, and adding insulation are the most common improvements auditors suggest. Attics can be the largest culprits for air and energy loss.