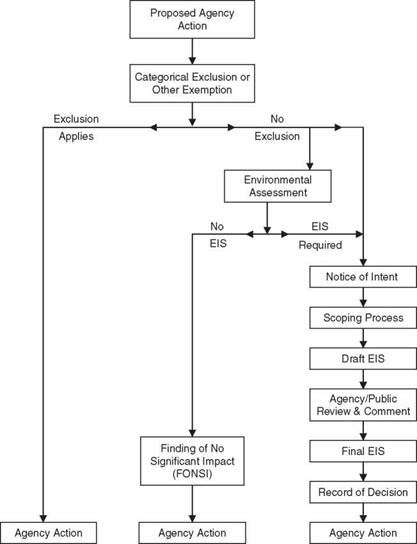

An outline of the steps in the NEPA process is presented in the following discussion and illustrated in Fig. 1.1.

Determination of the Level of Documentation Needed to Comply with NEPA.

Highway projects are usually initiated by a state or local transportation agency. If it is anticipated that a major federal action is required to implement a project, it must comply with NEPA. Conversely, projects that do not require a major federal action do not require review under NEPA. These minor actions include projects that are “categorically excluded” from detailed review under NEPA and for which a minimal level of environmental documentation is required. A list of categorical exclusions is provided

|

FIGURE 1.1 Overview of NEPA environmental review process. (From R. E. Bass and A. I. Herson, Mastering NEPA: A Step-by-Step Approach, Solano Press Books, Point Arena, Calif., 1993, with permission)

|

in Tables 1.2 and 1.3. The following are examples of actions that would trigger the need to comply with NEPA.

• The proposed use of federal funds for the planning, engineering, or construction of a project, or for needed right-of-way acquisition

• Modifications to an existing interstate highway

• Modifications to a non-interstate access-controlled highway that affects the right-of-way previously financed with federal funds

TABLE 1.2 Actions Categorically Excluded from Further Review by FHWA

1. Activities that do not involve or lead directly to construction

2. Approval of utility installations along or across a transportation facility

3. Construction of bicycle and pedestrian lanes, paths, and facilities

4. Activities included in the state’s highway safety plan under 23 USC §402

5. Transfer of federal lands pursuant to 23 USC §317 when the subsequent action is not an FHWA action

6. Installation of noise barriers or alterations to existing publicly owned buildings to provide for noise reduction

7. Landscaping

8. Installation of fencing, signs, pavement markings, small passenger shelters, traffic signals, and railroad warning devices where no substantial land acquisition or traffic disruption will occur

9. Emergency repairs under 23 USC §125

10. Acquisition of scenic easements

11. Determination of payback under 23 CFR §480 for property previously acquired with federal – aid participation

12. Improvements to existing rest areas and truck-weigh stations

13. Ride-sharing activities

14. Bus and railcar rehabilitation

15. Alterations to facilities or vehicles in order to make them accessible for elderly and handicapped persons

16. Program administration, technical assistance activities, and operating assistance to transit authorities to continue existing service or increase service to meet routine changes in demand.

17. Purchase of vehicles by the applicant where the use of these vehicles can be accommodated by existing facilities or by new facilities which themselves are within a categorical exclusion

18. Track and railbed maintenance and improvements when carried out within the existing right – of-way

19. Purchase and installation of operating or maintenance equipment to be located within the transit facility and with no significant impacts off the site

20. Promulgation of rules, regulations, and directives

Source: Adapted from 23 CFR 771.117(c).

If a project is subject to NEPA, a determination must then be made regarding the level of analysis and process to be completed to comply with NEPA. The type of environmental documentation that is required must be made in consultation with FHWA, which, in turn, coordinates the review of a proposed action with other involved federal agencies. Based on coordination with FHWA, a project could require one of the three levels of environmental documentation:

• Documentation supporting the project status as a categorical exclusion (CE).

• Projects for which an environmental assessment is required to make a final determination of whether an Environmental Impact Statement is required.

• Projects for which an environmental impact statement is required.

TABLE 1.3 Actions Generally Excluded from Further NEPA Review But Subject

to FHWA Approval

1. Modernization of a highway by resurfacing, restoration, rehabilitation, reconstruction, adding shoulders, or auxiliary lanes

2. Highway safety or traffic operations improvement projects, including the installation of rampmetering control devices and lighting

3. Bridge rehabilitation, reconstruction, or replacement or the construction of grade separation to replace existing at-grade railroad crossings

4. Transportation corridor fringe parking facilities

5. Construction of new truck weigh stations or rest areas

6. Approvals for disposal of excess right-of-way or for joint or limited use of right-of-way, where the proposed use does not have significant adverse impacts

7. Approvals for changes in access control

8. Construction of new bus storage and maintenance facilities in areas used predominately for industrial or transportation purposes where such construction is not inconsistent with existing zoning and located on or near a street with adequate capacity to handle anticipated bus and support vehicle traffic

9. Rehabilitation or reconstruction of existing rail and bus buildings and ancillary facilities where only minor amounts of additional land are required and there is not a substantial increase in the number of users

10. Construction of bus-transfer facilities (an open area consisting of passenger shelters, boarding areas, kiosks, and related street improvements) when located in a commercial area or other high-activity center in which there is adequate street capacity for projected bus traffic

11. Construction of rail storage and maintenance facilities in areas used predominatly for industrial or transportation purposes where such construction is not inconsistent with existing zoning and where there is no significant noise impact on the surrounding community

12. Acquisition of land for hardship or protective purposes

Source: Adapted from 23 CFR 771.117(d).

A determination of the extent of environmental documentation is based on a preliminary environmental evaluation of a proposed action to determine whether:

• The proposed action falls within the definitions of projects that are categorically excluded from NEPA review.

• The proposed action has the potential to result in one or more significant environmental impacts.

• Measures are reasonably available that could mitigate potential environmental effects thereby eliminating the potential for significant environmental impacts.

• The project has unusual level of public controversy that may warrant preparation of an EIS.

Categorical Exclusions. CEQ regulations implementing NEPA (40 CFR 1508.4) require that each federal agency identify the types of actions under its purview that would not individually or cumulatively result in significant environmental impacts. These projects, designated as categorical exclusions, are exempt from the need to prepare an EA or EIS.

FHWA has identified two sets of projects that may be categorically excluded from detailed review under NEPA. The first group of actions is found in 23 CFR 771.117(c) and

is provided in Table 1.2. These are actions that have been categorically found not to result in significant adverse environmental impacts. The second group of actions is found in 23 CFR 771.117(d) and is provided in Table 1.3. These include actions that have been found generally not to result in significant adverse environmental impacts, but for which FHWA must make a final determination.

When satisfied that the project meets one or more exclusion criteria and that other environmentally related requirements have been met, FHWA will indicate approval by signing a Categorical Exclusion form. A copy of documentation required to support this determination must be sent to FHWA by the sponsoring agency.

In certain cases, FHWA has reached agreement with sponsoring agencies on the treatment of very routine, repetitive projects with little or no environmental impact implications. Such projects may be processed on the basis of a “programmatic” categorical exclusion if certain specified conditions are met. Use of this programmatic process is subject to annual review by FHWA.

Classification of a project as a categorical exclusion does not exclude a project from the requirements of other federal environmentally related processes. These requirements must be met before FHWA will make an exclusion determination. In addition, Congress may, at its discretion, also exempt a specific federal project or program from NEPA through specific legislation.

Environmental Assessments. An EA is conducted for projects that are not categorically excluded and for which it is not clear whether an EIS is required. The primary purpose of an EA is to help FHWA decide whether an EIS is needed. Consequently, an EA should provide the evaluations critical to determining whether a proposed action would result in a significant impact on one or more of the environmental resources considered under NEPA, thereby necessitating a more complete analysis in an EIS. If it is determined that a proposed action does not have the potential to result in one or more significant environmental impacts, then FHWA will issue a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), thereby terminating the environmental review process under NEPA. If it is determined that a proposed action has the potential to result in one or more significant impacts, then FHWA has the option to require that an EIS be prepared.

Contents and Format of an EA. The contents of an EA are determined through agency and public scoping, preliminary data gathering, and field investigation. These steps will identify potentially affected resources and the level of analysis that is necessary to identify whether an action would have the potential to result in a significant environmental impact.

The EA should be a concise document, including only the data and technical analyses needed to support decision making, and be focused on determining whether the proposed action would have a significant effect on the environment. It is not necessary to provide detailed assessments of those resources for which significant environmental impacts are very unlikely.

In addition to a cover sheet and table of contents, the following elements should be included in an EA:

• Purpose and need for the proposed action

• Project description and alternatives

• Environmental setting, impacts, and mitigation

• Comments and coordination

• Appendices (as necessary)

• Section 4(f) evaluation (if required)

• EA revisions (if required)

Purpose and Need for the Proposed Action. A succinct description of the purpose and need for the proposed action should be provided at the beginning of the EA. The need for the project should be based on an objective evaluation of current information and future anticipated conditions. This section of the EA should identify the transportation problem(s) or other needs which the proposed action is intended to address (40 CFR 1502.13). The section should clearly demonstrate that a need exists and should define the need in terms understandable to the general public. The statement of purpose and need will form the basis for identifying of reasonable alternatives and in selecting a preferred alternative.

Consistent with joint FHWA and Federal Transit Administration (FTA) guidance (July 23, 2003 Joint Memorandum from Mary E. Peters, administrator of FHWA and Jennifer L. Dorn, administrator of FTA), the Purpose and Need Statement must be as concise and understandable as possible. Although it serves as the cornerstone for the subsequent identification and evaluation of alternatives, it should not specifically discuss any alternative or range of alternatives, nor should it be so narrowly drafted that it unreasonably points to a single solution, thereby circumventing necessary environmental review before a selection is made. In general, the “need” for an action should be defined as the transportation system deficiencies that will be addressed by the action, while the “purpose” for the action should be described as the objectives that will be met to address the deficiencies. Table 1.4 identifies the types of information that could be incorporated into the EA to demonstrate the need for a proposed action.

Project Description and Alternatives. Included in this section of the EA should be a project description written in clear, nontechnical language. It should include the location and geographic limits of the project and its major design features and typical sections; a location map (district, regional, county, or city map depicting state highways, major roads, and well-known features to orient the reader to the project location); a vicinity map

TABLE 1.4 Information to Establish Need for Highway Projects

Project status: Briefly describe the project history including actions taken to date, other agencies and governmental units involved, action spending, schedules, etc.

System linkage: Is the proposed project needed as a “connecting link”? How does the project fit in the transportation system?

Capacity: Is the capacity of an existing facility inadequate for the present and projected traffic? Would the proposed project provide needed additional capacity? What is the level(s) of service for existing and proposed facilities?

Transportation demand: Is the project identified in an adopted statewide or metropolitan transportation plan as needed to meet current or projected demand?

Legislation: Is there a federal, state or local governmental mandate for the action?

Social demands or economic development: Is the project needed to address projected economic development or changes in land use?

Modal interrelationships: Is the proposed project needed to interface with and complement airports, rail and port facilities, or mass transit services?

Safety: Is the proposed project needed to correct an existing or potential safety hazard? Is the

existing accident rate excessively high compared to that of similar facilities in the region or state?

Roadway deficiencies: Is the proposed project needed to correct existing roadway deficiencies (e. g., substandard geometrics, load limits on structures, inadequate cross-section, or high maintenance costs)?

(detailed map showing project limits and adjacent facilities); current status of the project including its relation to regional transportation plans, regional transportation improvement programs, congestion management plans, and the state transportation improvement program; proposed construction date; funding source(s); and the status of other projects or proposals in the area. For projects that include more than one type of improvement, the major design features of each type of improvement should be included.

The description of the project should clearly indicate the independence of the action by

• Identifying and providing the basis for establishing the “logical termini” (project limits) of the action

• Establishing the separate utility of the action from other actions of the agency

• Establishing that the action does not foreclose the opportunity to consider other actions

• Confirming that the action does not irretrievably commit federal funds for closely related projects

Reasonable alternatives to the project should be discussed, including consideration of a no-action option, which is mandated under both CEQ and FHWA regulations. The EA may either discuss (1) the preferred alternative and identify any other alternatives considered or

(2) if a preferred alternative has not been identified during previous planning studies, the alternatives under consideration. The EA does not need to evaluate in detail all reasonable alternatives for the project, and may be prepared for one or more build alternatives.

Project alternatives can be classified into two types: viable, and those studied but no longer under consideration. Viable alternatives should be described in sufficient detail to compare their effectiveness against the proposal in meeting the project purpose and need, and to assess potential impacts and estimate cost. Alternatives no longer under consideration should be explained briefly and the reasons provided for their elimination.

Environmental Setting, Impacts, and Mitigation. The EA should include a description of the environmental setting in which the proposed action would be located. The description should be succinct and maximize the use of visual displays to reduce the need for extensive narrative. Beyond a general description of contextual background, the discussion should focus on those features that have the greatest potential to be significantly affected by the proposed action.

The EA should discuss any social, economic, and environmental impacts whose significance is uncertain. The level of analysis should be sufficient to adequately identify the impacts and available measures to mitigate impacts, and to address known and foreseeable public and agency concerns. Impact areas that do not have a reasonable possibility for individual or cumulative environmental impacts need not be addressed. The reasons for determining why any impacts are not considered to be significant should be provided.

If more than one alternative is involved, the evaluation must identify the impacts associated with each alternative being evaluated. The EA should identify the technical studies and backup reports used in making the assessment and indicate where they are available. A list of environmental resource categories to be considered in both EAs and EISs is included in Table 1.5.

Feasible measures that reduce or eliminate potential impacts of a proposed action should be identified. Measures may be presented as potential commitments that may be selected for implementation by the lead agency. Alternatively, these measures can be incorporated as elements of the proposed action, thus avoiding impacts. Measures to mitigate impacts may diminish the intensity of project effects to the point that they would not be considered to be significant, and could make the project eligible for a FONSI.

Based on the results of these evaluations, a determination is made of whether the anticipated effects of the project represent a significant environmental impact thereby requiring

TABLE 1.5 Environmental Resource Categories to Be Considered in the Preparation of Environmental Assessments and Environmental Impact Statements

1. Land use impacts

2. Farmland impacts

3. Socioeconomic impacts, including disproportionate adverse impacts on disadvantaged and minority populations (environmental justice)

4. Relocation impacts

5. Considerations relating to pedestrians and bicyclists

6. Air quality impacts

7. Noise impacts

8. Water quality impacts

9. Wetland impacts

10. Water body modification and wildlife impacts

11. Floodplain impacts

12. Wild and scenic rivers

13. Coastal barriers

14. Coastal zone impacts

15. Threatened or endangered species

16. Historic and archeological preservation

17. Hazardous waste sites

18. Visual impacts

19. Energy

20. Construction impacts

21. Relationship of local short-term uses vs. long-term productivity

22. Irreversible and irretrievable commitment of resources

23. Cumulative impacts

the preparation of an EIS. This determination is based on a review of the context and intensity of the impact. Context refers to the setting within which the proposed project is being developed. Intensity refers to the severity of an impact and will vary by resource type.

Factors to consider in determining intensity of an impact include

• The degree to which the action may affect public health or safety.

• The degree to which the effects on the quality of the human environment may result in a significant level of public controversy.

• Whether the action may result in cumulatively significant impacts when added to the effects of other planned and programmed projects and activities separate from the proposed action.

• Whether the action has the potential to violate one or more federal, state, or local laws or standards intended to protect the environment.

Factors to be considered in determining the context include

• Unique characteristics of the geographic area such as proximity to public, park lands, prime farmlands, wetlands, wild and scenic rivers, or ecologically critical areas.

• The degree to which the action may adversely affect districts, sites, highways, structures, or objects listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

• The degree to which the action may adversely affect threatened or endangered species of their habitat that has been determined to be critical under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

Comments and Coordination. Determination of the need for an EIS or whether the FHWA can issue a FONSI can only be made after the EA has been made available for agency and public review. This section of the EA should summarize the efforts taken to coordinate with agencies and the public, identify the key issues and pertinent information received through these efforts, and list the agencies and members of the public consulted.

Public involvement is an essential element of the NEPA process, and the proposing agency must take proactive steps to encourage and provide for early and continuing public participation in the decision-making process [40 CFR 1506(a)]. Opportunities for public involvement are provided at several stages during the development of NEPA documents, such as at the publication of the notice of intent (NOI) to prepare an EIS, during the process used to scope the environmental document, and during the process afforded to agencies and the public to review the environmental document.

Opportunity for the public to review and comment on the completed (draft) EA occurs upon publication of a notice of availability of the draft document. Such notice may be published in local newspapers or other local print media, presented in special newsletters, provided to community and business associations, placed in legal postings, and presented to interested Native American tribes, if appropriate. For an EIS, publication of such notice is also required in the Federal Register. Notices and other public announcements regarding the project should be sent individually to those who have expressed an interest in a specific action.

Early incorporation of public input on project alternatives and issues dealing with social, economic, and environmental impacts helps in deciding whether to prepare an EIS, in determining the scope of the document, and in identifying important or controversial issues to be considered. When impacts involve the relocation of individuals, groups, or institutions, special notification and public participation efforts should be undertaken. Early and ongoing public involvement will assist in gaining consensus on the need for the action and in identifying and screening alternatives.

A public hearing is not mandated to receive comment on an EA but is required for public review of a draft EIS. The proposing agency must provide for one or more public hearings to be held at a convenient time and place for federal actions that require significant amounts of right-of-way acquisition, substantially change the layout or function of connecting roadways or of the facility being improved, have substantial adverse impact on abutting properties, or otherwise have a significant social, economic, or environmental effect [23 CFR 771.111(h)(2)(iii)].

During public hearings, the public should be provided with information on the project’s purpose and need and with how the project relates to local and regional planning goals, the major design features of the project, its potential impacts, and the reasonable alternatives under consideration including the no-action alternative. Areas of special interest to the public, such as needed right-of-way acquisition and the proposed displacement and relocation of existing uses, should be carefully explained, as should the agency’s procedures and timing for receiving oral and written public comments [23 CFR 771.111(h)(2)(v)]. The public comment period for a draft EIS is at least 45 days. All public comments received during the public comment period, including during public hearings must be documented.

Appendices (if any). Appendices to the EA should include the analytical information that substantiates the principal analyses and findings included in the main body of the document.

Section 4(f) Evaluation (if any). As described in Art. 1.2 of this chapter, a Section 4(f) evaluation may be required if a project would require the use of land from a significant publicly owned public park, recreation area, or wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or any significant historic site. If a Section 4(f) evaluation is required, it may be included as a section within the EA. If included within the EA, a separate “avoidance alternatives evaluation” need not be repeated in the EA. In all cases, the Section 4(f) evaluation must be circulated for review in conformance with 23 CFR 771.135(i) requirements.

EA Revisions. An EA should be revised subsequent to public review to (1) reflect changes in the proposed action, impact assessment, or mitigation measures resulting from comments received on the EA, (2) include any necessary findings, agreements, or determinations made as a consequence of the concurrent reviews under Section 4(f) or other regulatory requirements, and (3) include a copy of pertinent substantive comments received on the EA and appropriate responses to the comments.

Finding of No Significant Impact. After review of the EA and any other appropriate information, the FHWA may determine that the proposed action would not result in any significant impacts, and issue a FONSI. The FONSI should briefly present the reasons why the proposed action would not have a significant effect on the human environment or require the preparation of an EIS. The FONSI should document compliance with NEPA and other applicable environmental requirements. If full compliance with all these other requirements is not possible by the time the FONSI is published, the FONSI should document consultation with the affected agencies to date and describe how and when the other requirements will be met.

There is no requirement to publish a record of decision (ROD) for a FONSI, nor is there a legally mandated requirement to distribute the FONSI. However, the FHWA must send a notice of availability of the FONSI to federal, state, and local government agencies likely to have an interest in the undertaking and the state intergovernmental review contacts [23 DFR 771.121(b)]. It is encouraged that agencies that have comments on the EA (or requested to be informed) be advised on the project decision and the disposition of their comments, and be provided a copy of the FONSI.

Environmental Impact Statement. A federal agency must prepare an EIS if it is proposing a major federal action that would significantly affect the quality of the human environment (40 CFR §1501.7). The regulatory requirements for an EIS are more extensive than the requirements for an EA. The steps to be followed in preparing an EIS are depicted in Fig. 1.1.

Once the lead agency determines that an action would result in a significant measurable impact, development of a draft enviornmental impact statement (DEIS) is initiated through a public and agency notification and scoping process focused on early identification of the major issues of concern and alternatives for study. This process includes confirmation of FHWA as the agency to lead the environmental review process, identification of cooperating agencies, distribution of a letter of initiation of the environmental process from the sponsoring agency, publication of a notice of intent to prepare an EIS, invitation to agencies to become participating agencies in the environmental review process, and completion of scoping activities. Each of these steps is described in the following discussion.

Lead Agency Determination. In accordance with Section 6002 of SAFETEA-LU, DOT is designated as the federal lead agency for the “environmental review process” for any surface transportation project that requires a DOT approval. The environmental review process includes both NEPA and other reviews. The lead agency is responsible for taking actions within its authority to facilitate the resolution of the environmental review process. It also is responsible for preparing the required NEPA document for the

project, or ensuring that one is prepared. Other federal agencies that have jurisdiction by law, or that have special expertise with respect to any environmental issue that should be addressed in the EIS may be a cooperating agency upon request of the lead agency. An agency may also request that the lead agency designate it as a cooperating agency. Each cooperating agency must (1) participate in the NEPA process at the earliest possible time,

(2) participate in the scoping process described below, (3) assume on request of the lead agency responsibility for developing information and preparing environmental analyses including portions of the EIS concerning issues which the cooperating agency has special expertise, and (4) make staff available to enhance the lead agency’s interdisciplinary capability.

Dissemination of Letter of Initiation. In accordance with Section 6002 of SAFETEA – LU, a project sponsor has the responsibility to notify DOT that the environmental review process for a project “should be initiated.” This notice of initiation, which can take the form of a letter or other form of notice, should identify the type of work, termini, length, and general location of the project. It should also identify any federal approvals that the project sponsor believes will be necessary, including all anticipated environmental reviews, permits, and consistency determinations.

Publication of Notice of Intent. The EIS process begins with the publication of a notice of intent (NOI) stating the agency’s intent to prepare an EIS for the proposed action. The NOI is published in the Federal Register, and provides basic information on the proposed action in preparation for a subsequent “scoping process.” The NOI should include a description of the purpose and need for the proposed action similar to that included in an EA. In addition, it includes a brief description of the proposed action and possible alternatives, and a description of the process proposed by the sponsoring agency to identify the scope of the EIS. This should include any proposed scoping meetings and other methods proposed for public involvement in the environmental review process. The NOI should also identify the agency point of contact for the project, who can respond to questions concerning the proposed action and the NEPA process. The NOI should emphasize the lead agency’s commitment to collaborate with others interested in the proposed action and to describe how it intends to engage interested parties throughout the analysis. The publication of the NOI in the Federal Register can be supplemented by issuing other forms of notice such as announcements on websites, newspapers, newsletters, and other forms of media. The format and content of the notice of intent are included in FHWA Technical Advisory T6640.8A.

Invitation to Participating Agencies. In addition to publication of an NOI, Section 6002 of SAFETEA-LU requires that the lead environmental agency designate as “participating agencies” (a new term created under SAFETEA-LU) all other governmental agencies—federal or nonfederal—that may have an interest in the project, and invite them to participate in the environmental review process for the project. Such designation and invitation should occur as early in the environmental review process as is practicable. Any federal agency that is invited to participate in the process must accept the invitation unless that agency notifies the lead agency in writing by the deadline specified in the invitation that (1) it has no jurisdiction or authority over the project, (2) it has no information or expertise relevant to the project, and (3) it does not intend to submit comment on the project.

Section 6002 of SAFETEA-LU further mandates that the lead agency must establish a plan for coordinating public and agency participation in the environmental review process, including for all federal environmental reviews for the project, not just DOT reviews. Optionally, the lead agency may establish a schedule for completion of the environmental review process after consultation with all participating agencies and the state and project sponsor. SAFETEA-LU directs “each federal agency, to the maximum extent practicable,” to (1) carry out all reviews required under other laws concurrently with the review required in NEPA, and (2) formulate and implement mechanisms to enable the agency to ensure the

completion of the environmental review process in a “timely, coordinated, and environmentally responsible manner.”

Scoping. “Scoping” is an early and open process for determining the breadth of issues to be addressed in an EIS, the range of alternatives to be considered, and the methods to be applied in evaluating the effects of an action. The objectives of scoping are to

• Invite the participation of affected federal, state, and local agencies, any affected Indian tribe, and other interested persons (including those who might not be in accord with the action on environmental grounds).

• Identify and eliminate from detailed study the issues that are not significant or that have been covered by prior environmental review.

• Allocate assignments for preparation of the EIS among the lead and cooperating agencies.

• Identify other environmental review and consultation requirements so FHWA and cooperating agencies may prepare other required analyses and studies concurrently with the EIS.

• Indicate the relationship between the timing of the preparation of environmental analyses and the planning and decision-making schedule.

Notification and implementation of scoping is achieved through public agency involvement procedures required by 23 CFR 771.111.

Preparation of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS). The principal purpose of the DEIS is to disclose to the decision makers and the public the probable impacts of reasonable alternative that have the potential to meet the purpose and need of a proposed action. Responsible decisions can be then made after public review and comment based on an assessment of the degree to which competing alternatives meet the need for the action and by balancing their relative environmental, social, and economic impacts.

Preparation of the DEIS should begin at the earliest practical time. A key element should be the early exploration of alternatives and their relative ability to meet the purpose and need for the proposed action. This will assist in identification of reasonable alternatives and allow early coordination with cooperating and responsible agencies.

The DEIS should be concise and include succinct statements, evaluations, and descriptions of conclusions. Lengthy, encyclopedic discussions of subject matter diffuse the focus of the document from its analytical purpose. The document should be easily understood by the public and written to emphasize the significant environmental impacts of competing alternatives. Discussions of less significant impacts should be brief, but sufficient to demonstrate that due consideration was given and more detailed study not warranted.

CEQ regulations emphasize brevity and stress the importance of focusing on significant issues and avoiding detailed discussion of less important matters. Normally, EISs should be less than 150 pages, or less than 300 pages if the action is unusual in scope and complexity. Exhibits (charts, tables, maps, and other graphics) are useful in reducing the amount of narrative required. Adequacy of a DEIS is measured by its functional usefulness in decision making, not by its size or amount of detail. This is especially applicable in the executive summary of the document, where items relating to alternatives and their impacts and related mitigation can be presented in a matrix format, thereby minimizing the need for narrative.

Contents and Format of the Draft EIS. In accordance with 40 CFR 1502.10 and FHWA Technical Advisory T6640.8A, an EIS should be prepared in accordance with the following outline unless compelling reasons to do otherwise are given by the proposing agency:

• Cover sheet

• Executive summary

• Title page

• Table of contents

• Purpose and need for the proposed action

• Alternatives

• Affected environment

• Environmental consequences

• Mitigation measures

• List of preparers

• List of who received copies

• Appendixes

• Index

Cover Sheet. The cover sheet should clearly indicate the name of the project, its location, date of publication of the DEIS, and the responsible sponsoring and environmental lead and cooperating agencies.

Executive Summary. A summary should be given that provides an overview of the entire DEIS and be no greater than 10 to 15 pages in length. The summary should include the following information:

• Briefly describe the proposed project, including the route, termini, type of facility, number of lanes, length, county, city, and state, along with significant appurtenances, as appropriate.

• List other federal actions required for implementation of the project, including required permits. Also describe other major actions proposed by other governmental agencies in the same geographic area as the proposed project.

• Summarize all reasonable alternatives considered.

• Summarize the major environmental impacts of each alternative, both beneficial and adverse.

• Identify proposed measures to reduce or avoid identified impacts.

• Briefly describe any areas of concern (including issues raised by agencies and the public) including any important unresolved issues.

Title Page. The title page should identify the name of the proposed action, and its geographic limits and location, the date of the DEIS, and any relevant report number identified by the sponsoring agency and FHWA. The proposing agency must be clearly identified, including the name, address, and telephone number of a primary contact person. All agencies that serve as cooperating agencies should also be identified. A brief one paragraph abstract should be included, providing a description of the proposed action and its alternatives, a summary of significant impacts, and major mitigation measures. The title page should also identify the date by which comments on the DEIS must be received.

Table of Contents. A table of contents should be included in the document and consider all areas of concern identified during the scoping process.

Purpose and Need of the Proposed Action. The DEIS should include a description of the purpose and need for the proposed action. The information provided should be similar to that provided in an EA, as described earlier in this chapter.

Alternatives. The lead agency must “objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives, and for alternatives which were eliminated from detailed study, briefly discuss the

reasons for their having been eliminated” (40 CFR §1502.14). Reasonable alternatives are those that substantially meet the purpose and need for the proposed action, and include those that are practical or feasible from the technical and economic standpoint, rather than simply desirable from the standpoint of the applicant or the public. Agencies are obligated to evaluate all reasonable alternatives or a range of reasonable alternatives in enough detail so that a reader can compare and contrast the environmental effects of the various alternatives.

Both improvement of existing highways and facilities on new locations should be considered, as appropriate to the need for the action. A representative number of reasonable alternatives must be presented and evaluated in detail in the DEIS. For most major projects, there is a potential for a large number of reasonable action alternatives. Only a representative number of the most reasonable approaches, covering the full range of alternatives, should be presented. The number of reasonable alternatives will depend on the project location and pertinent project issues. Each alternative should be briefly described using maps or other visual aids such as photographs, drawings, or sketches. A clear description should be presented of the concept, major design features, termini, location, and costs for each alternative. More detailed design of some aspects may be necessary for one or more alternatives to evaluate impacts or mitigation measures, or to address issues raised by other agencies or the public. However, equal consideration must be given to all alternatives. All reasonable alternatives considered should be developed to a comparable level of detail in the draft EIS so that their comparative merits may be evaluated. Where a preferred alternative has been identified, it should be so indicated. The DEIS should include a statement that the final selection of an alternative will not be made until the impacts of the alternatives and public comments on the DEIS have been fully evaluated. Where a preferred alternative has not been identified, the DEIS should state that all reasonable alternatives are under consideration and that a decision will be made only after the impacts of the alternatives and comments on the DEIS have been fully evaluated.

Both CEQ and FHWA regulations implementing NEPA require consideration of a “no-action” alternative. The no-action alternative is the condition that would occur if FHWA did not implement the proposed action, but may be different from the existing condition due to implementation of other actions separate from those of the proposed action if the proposed action was not authorized. For highway projects, the no-action alternative would at least include those reasonably foreseeable maintenance and safety actions required to continue operation of the facility under consideration.

Affected Environment. This section of the DEIS describes in concise terms the social, economic, and environmental setting for the alternatives under consideration. The limits of the study area(s) should be based on an assessment of the extent of potential impact for each impact category. Impact categories should include those listed in Table 1.5. Only aspects of the setting relevant to assessing the environmental impacts of proposed alternatives should be discussed in detail, with other descriptions limited to that necessary to provide context.

Environmental Consequences. The major significant impacts of the project should be discussed in detail in the environmental consequences section for each of the categories for which a description of the affected environment is provided. The analysis of impacts should consider all issues raised during the project’s public and agency-scoping process. The analysis must include consideration of the full range of short – and long-term, and direct, indirect, and cumulative effects of the preferred alternative, if any, and of the reasonable alternatives identified in the alternatives section of the DEIS. Effects to be considered include ecological, aesthetic, historic, cultural, economic, social, and public health impacts, whether adverse or beneficial (40 CFR §§1508.7, 1508.8).

Mitigation Measures. This section of the DEIS should specify measures to lessen the adverse environmental impacts of alternatives identified in the environmental consequences

section of the DEIS. For an impact mitigation measures to be considered usable it must be effective, economically feasible and the agency must be capable of and committed to implementing the measure. Under CEQ regulations, mitigation can be achieved by avoiding the adverse impact, minimizing the adverse effect by reducing the scope of the project, implementing a program to reduce the impact over time, or compensating for the impact by replacing or providing substitute resources.

List of Preparers. A list should be provided of the names and appropriate qualifications (professional license, academic background, certification, professional working experience, and special expertise) of the persons who were principally responsible for preparing the DEIS or substantial background papers. The list should include any project sponsor, FHWA and consultant personnel who had primary responsibility for preparing or reviewing the DEIS.

DEIS Distribution List. The draft EIS must list the names and addresses of the agencies and organizations that were sent copies of the DEIS for review.

Comments and Coordination. The draft EIS should contain pertinent correspondence summarizing public and agency coordination, meetings, and other pertinent information received.

Glossary and Abbreviations. A glossary and list of abbreviations should be included as an aid to those not familiar with the project development process and technical issues being considered in the DEIS.

References and Bibliography. A clear, concise listing of references and bibliographical material should be included.

Appendices. Appendices should contain the reports and documents that support the findings of the DEIS. Detailed technical discussions and analyses that substantiate the concise statements within the body of the DEIS are most appropriately placed in the appendices. Appendices must either be circulated with the draft EIS or be readily available for public review.

Index. An index to the DEIS should be provided to assist the reader in locating topics of interest.

Public Re-view and Comment. Upon completion, the DEIS is made available for public review and comment. Review of the DEIS should supplement the public outreach activities to date. A notice of availability of the DEIS should be published in the Federal Register and in newspapers of general circulation in the vicinity of the project site. Hard copies of the DEIS should be provided at libraries and other locations in the vicinity of the geographic area that would be potentially affected by the proposed action. Electronic copies of the DEIS and its supporting documentation should also be made available on the website of the sponsoring agency. Provisions should be made for major foreign language populations in the area, including the publication of notices in the language of major non-English speaking populations in the area, and the provision of translators at any public hearings.

The notice of availability of the DEIS should indicate the date by which public comments must be received and the dates, times, and locations of any public hearing(s) on the DEIS. Adequate notice should be provided to any public hearings to allow sufficient time for public examination and assessment of the DEIS. All substantive comments received on the DEIS during the public review period, including all written comments and oral comments received at any public hearing on the DEIS, should be documented and summarized. Responses must be prepared to all substantive comments. Responses to nonsubstantive comments and gratuitous remarks on the DEIS are not required.

Final EIS. Upon completion of the public comment period on the DEIS, an analysis is completed of the comments received, necessary revisions are made to the analyses and

Content

Content

|

Cover sheet Executive summary

|

|

|

The cover sheet must indicate FEIS.

The executive summary should incorporate any changes between the DEIS and FEIS, identify the preferred alternative, and concisely describe all mitigation measures, including monitoring and enforcement measures for any proposed mitigation measure, where applicable.

No revisions from the DEIS unless warranted by comments received on the DEIS.

The preferred alternative should be identified and

described in a separate section of the FEIS. A defensible rationale should be provided for selection of the preferred alternative. This rationale must reflect a comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of the various alternatives considered.

No substantive change from that included in the DEIS unless warranted by comments received on the DEIS.

No substantive changes unless warranted by comments received on DEIS.

The FEIS should identify all mitigation measures.

No substantive change unless comments warrant.

No substantive change unless comments warrant.

No substantive change unless comments warrant.

No substantive change unless comments warrant.

Indicate on the list those entities commenting.

This section provides a list of those commenting on the DEIS, including copies of comments received and responses to all substantive comments.

|

|

|

Need for action Alternatives

|

|

|

Affected environment

Environmental consequences

Mitigation and other

List of preparers

List of who received DEIS

Appendixes

Index

Distribution list Comments and coordination

|

|

conclusions in the DEIS, and a final EIS (FEIS) is prepared. The FEIS must document and include responses to all substantive comments received on the DEIS from public agencies and the public (40 CFR §1502.18). Responses to comments can be made in the form of changes to the text and analyses included in the DEIS, factual corrections, new alternatives considered or an explanation of why a comment does not require a response (40 CFR §1503.4). A copy or summary of substantive comments and the responses to them must be included in the FEIS [40 CFR §1503.4(a)]. The contents of an FEIS is provided in Table 1.6.

If not already identified in the DEIS, the FEIS should identify the preferred alternative to be recommended for implementation. The preferred alternative could be one of the reasonable alternatives considered in the DEIS or an alternative that is a composite or variant of the reasonable alternatives considered in the DEIS.

If the preferred alternative will involve the use of a resource protected under Section 4(f), a final Section 4(f) evaluation must be prepared and included as a separate section of the FEIS or as a separate document.

When completed, the FHWA will publish the FEIS and EPA will publish a notice of availability of the FEIS in the Federal Register. A minimum of 30 days must pass after publication of the FEIS before FHWA can make a final decision on the proposed action (40 CFR §1504).

Record of Decision. Preparation and publication of a record of decision (ROD) by FHWA is the final step in the EIS process. The ROD documents the decisions made by FHWA for the proposed action, including identification of the preferred alternative, and the measures identified to mitigate any identified adverse impacts of the preferred alternative, including the commitments and plans to enforce and monitor implementation of the measures (40 CFR §1505.2). The ROD also discloses the bases for the agency’s decision, including the reasons for whether to proceed with the proposed action. The ROD must also discuss whether all practical means have been applied to avoid or minimize environmental harm have been adopted, and, if not, why they were not (40 CFR §1505.2). The ROD must be made publicly available by publication in the Federal Register or on the agency website, or both.

Environmental Reevaluation and Supplemental EIS. An environmental reevaluation (ER) of the FEIS is prepared when any of the following circumstances occur:

• An acceptable FEIS is not submitted to FHWA within 3 years from the date of circulation of the DEIS.

• No major steps have been taken to advance a project (e. g., allocation of a substantial portion of right-of-way or construction funding) within 3 years from the date of approval of the FEIS.

• When there have been lengthy periods of inactivity between major steps to advance the project.

The purpose of the reevaluation is to determine whether there has been a substantial change in the social, economic, and environmental effects of the proposed action. This could result from changes in the project itself or from changes in the context under which the project is to be undertaken.

A supplemental EIS should be prepared when there are changes that result in significant impacts not previously disclosed in the original document. An EIS may be supplemented or amended at any time and must be supplemented or amended when (1) changes to the proposed project would result in significant environmental impacts that were not disclosed in the EIS or (2) new information or circumstances relevant to environmental concerns and bearing on the proposed project or its impacts would either bring to light or result in significant environmental impacts not evaluated in the original document. The supplemental EIS need only address those subjects in the original document affected by the changes or new information.

Elevation plan to show how each side of the house will look. Elevation drawings show the foundation, wall height, siding and trim, roof

Elevation plan to show how each side of the house will look. Elevation drawings show the foundation, wall height, siding and trim, roof

style and pitch, and roof overhang at the eaves.

style and pitch, and roof overhang at the eaves.![STEP 4 SECURE THE BUILDING PERMITS Подпись: Many hands, one goal. Working together gets the job done. [Photo by HFHI/Gregg Pachkowski]](/img/1312/image045_1.gif)

Schedule and have inspections for the rough framing and the electrical, plumbing, and heating systems.

Schedule and have inspections for the rough framing and the electrical, plumbing, and heating systems.

H ave the trim—door and window casings, baseboards, windowsills, aprons, and closet shelves and poles—delivered. Install the trim.

H ave the trim—door and window casings, baseboards, windowsills, aprons, and closet shelves and poles—delivered. Install the trim.

Schedule the final inspection.

Schedule the final inspection.

Use your pocketknife to prod for damage under lavatory and kitchen sink cabinets. Rusted – out drainpipes or leaking supply-pipe connections are easily replaced, but extensive water damage can be costly to remedy.

Use your pocketknife to prod for damage under lavatory and kitchen sink cabinets. Rusted – out drainpipes or leaking supply-pipe connections are easily replaced, but extensive water damage can be costly to remedy.