INSTALLING FRIEZE BLOCKS BETWEEN. RAFTERS AND TRUSSES

![]()

2x frieze block

Rafter

Double top plate

Stucco

When installed plumb, a frieze block provides backing for stucco.

2x frieze block

Siding

Trusses by themselves are rather fragile. They gain strength when they’re properly blocked and braced. I will now explain various blocking and bracing strategies, because this work needs to be done as the trusses are installed.

Hurricane clips and frieze blocks

A hurricane can tear a roof completely off a house. Hurricane clips, which are designed to prevent this, are required by code in some parts of the country. After the trusses are nailed in position, hurricane clips are easy to install from inside or outside the house. Drive nails into the trusses and the top plates of the wall (see the bottom left photo). Be sure to use the special short, strong “hanger” nails that are sold with the clips.

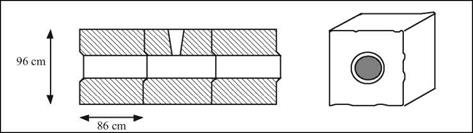

In many parts of the country, frieze blocks are required between trusses. I’m in favor of these blocks, which you can cut from the plentiful supply of 2x scrap that your crew has been collecting. Installed at the top of the wall, these 2x blocks connect the bottom chords or, depending on the truss design, the rafters of adjacent trusses. They provide extra rigidity near the truss ends (see the illustration at left).

I have seen firsthand how frieze blocks help hold truss systems together in high winds and earthquakes. They offer other benefits as well. The blocks can serve as exterior trim (with or without ventilation holes) if you plan to have an open soffit. If you are installing raised-heel trusses, as we did on this house, you’ll also need to install plywood or OSB baffles between the trusses to prevent attic insulation from spilling into the soffit area (see the top photo on p. 153).

Install a pair of frieze blocks after each truss is installed. Drive a pair of 16d nails

Hurricane clips tie trusses to walls. Required by code in many areas, these metal connectors are designed to fit around the bottom chord of a truss and against the top plate of a wall. Here, a volunteer attaches a clip with an air hammer.

through the truss and into the end of the frieze block, then nail the frieze block to the top plate. You can cut a supply of blocks quickly on a chopsaw. Make sure you cut them to the correct length. If they’re too long or too short, you may force the trusses off of their layout. The normal block length for trusses spaced 2 ft. o. c. is 22У2 in. However, if the blocks will butt against gusset plates, you’ll need to take the gusset thickness into account.

After you’ve nailed the first frieze blocks to the gable-end truss, swing the next truss upright. Shift it right or left, as necessary, to obtain the correct eave overhang, then toenail it to the top plate with two 16d nails through the joist chord on one side and one 16d nail on the other side (see the bottom photo at right). Install the next several trusses in this fashion. As you raise each truss, tack a series of 16-ft. 1x4s (laid out 24 in. o. c.) near the ridge of the rafter chord to keep the truss stable and properly spaced (see the top photo at right).

An efficient way to work when installing roof trusses is to have a worker at each eave toe – nailing the truss to the wall and installing frieze blocks while one or two crew members work on the ridge, moving trusses into position and nailing 1×4 braces to maintain proper spacing.

Unless the trusses were set on the walls at the time of delivery, they must be hoisted onto the walls by hand (see the photo on the facing page). One way to do this is to set good, strong ladders at both corners of the building. If you’re dealing with long trusses, place a 2x in the center, from the ground to the top plate, at the same angle as the ladders. This way, two people can lift a truss, lay it against the ladders and the center 2x, and walk it up to the top. Another person in the middle with a notched pole can push on the truss as needed.

Unless the trusses were set on the walls at the time of delivery, they must be hoisted onto the walls by hand (see the photo on the facing page). One way to do this is to set good, strong ladders at both corners of the building. If you’re dealing with long trusses, place a 2x in the center, from the ground to the top plate, at the same angle as the ladders. This way, two people can lift a truss, lay it against the ladders and the center 2x, and walk it up to the top. Another person in the middle with a notched pole can push on the truss as needed.