Hydraulics and prosperity in the heart of the Arab world

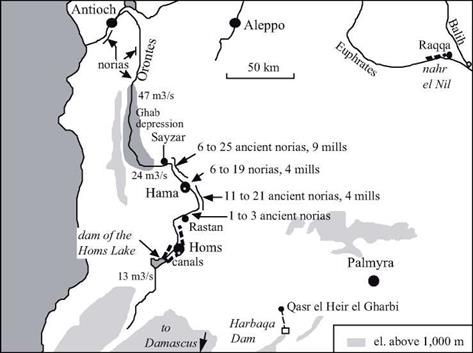

Arab agriculture included exotic crops such as cotton, rice, and sugar cane in addition to traditional grains and fruits. Cotton was known in Mesopotamia since the time of the Assyrians, but was essentially undeveloped. These crops require considerable water, and therefore are grown in the large irrigable zones on the shores of the Khabur, the Euphrates, and the Tigris.[325] The Muslim world uses all known existing techniques to develop irrigation. This includes derivation canals from rivers and wadis, water-lifting machines, and even drip irrigation for young plants, a technique known since the 5th century and wonderfully described in an Arab work of the 12th century.[326] The shaduf is used to lift water out of rivers and canals, but on a small scale. The bucket chain or saqqiya and the noria, are the most widely used devices. The noria sees considerable application, especially on rivers of regular flow such as the Orontes and the Khabur, and also on the middle Euphrates. We will come back to this point further on.

Qanats exist also, but it is usually impossible to tell if the origin of a particular installation is Arab, Roman, or even earlier. In Syria (where they are called foggaras), there are 45 qanats in the Palmyra region, 50 in the ghouta of Damascus, 35 between Damascus and Homs, 20 to the southeast of Homs, 50 to the east of Hama, 15 to the southwest of Aleppo, and 25 to the east of Aleppo.[327] [328] In the 12th century, Ibn Jubayr takes note of them between Homs and Damascus:

“We camped in a large village of Christians called al-Qara where no Muslim lived, and that has a caravanserai much like that of a large fortress. In the center, one can see a large basin

that is always full of water, supplied by an underground stream coming from a distant „30

source.

This axis Aleppo – Hama – Homs – Damascus, in Syria, is particularly developed and irrigated. We mentioned above the qanats, frequently encountered along this corridor, as well as the water taken from the Barada for the ghouta of Damascus (Figure 7.6).

Homs is irrigated using canals issuing from the Roman dam of Homs lake (Figure 6.33).

The steep banks of the Orontes at and around the city of Hama are irrigated thanks to large, numerous, and particularly famous norias (Figure 7.9). The oldest of these norias to which a date can be assigned (for its canal carries an inscription) was constructed in 1361 (Figure 7.7). But one cannot separate the norias from the city of Hama; in 1185, Ibn Jubayr tells us they were already there:

“On the two banks (of the Orontes), starting from the hydraulic wheels and extending regularly out, are gardens, whose tree branches hang over the water. […] On one of the banks that borders the outlying district one finds washing stations arranged like several rooms; the water, raised by a hydraulic wheel, crosses into all the hidden crannies.”[329]

Figure 7.7 The noria al-Muhammadiya and its aqueduct at Hama, dated as 1361 from the inscription on a pillar of the aqueduct. As are the other norias of Hama, this one has been maintained and regularly renovated since its initial construction. With a diameter of 21 m, it is the largest known ancient noria (photo by the author).

Figure 7.7 The noria al-Muhammadiya and its aqueduct at Hama, dated as 1361 from the inscription on a pillar of the aqueduct. As are the other norias of Hama, this one has been maintained and regularly renovated since its initial construction. With a diameter of 21 m, it is the largest known ancient noria (photo by the author).

![]() k»*’

k»*’

Figure 7.8 The group called the “four norias” at the entrance of the Orontes into Hama. The aqueduct of the two norias at the right has disappeared (photo by the author).

The remains of some fifteen of these norias (or the gardens that they irrigated) can be found in the archives of the 16th century of the tribunal of Hama.[330]

Qanats and norias are costly devices that provide copious quantities of water. Therefore social organization is needed to regulate their use. In the Muslim world, periodic hourly time schedules are established at a scale of about ten days. In the Syrian areas irrigated by qanats to the north of Damascus, irrigation periods are every twelve days, or rather every 24 half-days (from two hours before dawn to two hours after sunset). The unit of time is one “hour” of a hundred minutes, and through an alternating schedule a user can draw water first for a daytime period, then a nighttime period.[331] At Hama, on the other hand, weekly cycles are used to allocate water from the norias among the fields, the mosque fountains, or the public baths.

In some cases, Roman hydraulic works are brought back into service. For example, when the tenth Umeyyade caliph Hisham (724 – 743) decides to build a palace in the

|

Figure 7.9 The valley of the Orontes, showing the locations of the ancient norias. The lower figure shown corresponds to the number of norias that can be reliably dated from the 16th century (from inscriptions and archive documents analyzed by Zaqzouq, 1990). The implantation of norias is particularly dense between Rastan and Sayzar, where the slope of the Orontes is a fairly regular 1.1 m/km. The indicated discharges are the mean flow of the Orontes at different points (after Delpech, girard, Robine, Roumi, 1997). |

|

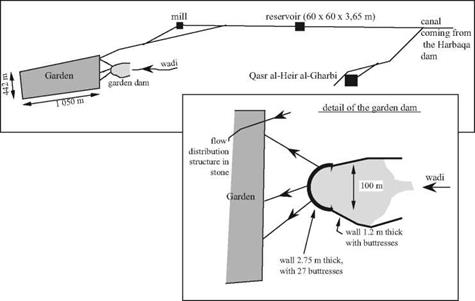

Figure 7.10 Layout of Umeyyade hydraulic installations at Qasr al-Heir al-Gharbi, and of the garden dam (after Sailby, 1990; Calvet and Geyer, 1992). |

desert of Palmyra in 727 (at the intersection of the caravan routes, on the road between the capital Damascus and the middle Euphrates), he makes use of the ancient Roman dam of Harbaqa (Figures 6.34, 7.9).[332] This palace, known as Qasr el-Heir el-Gharbi, is supplied by an underground canal issuing from this dam that is 16.5 km long. The aqueduct supplies a reservoir that is 60 m on a side and 3.65 m deep. The aqueduct also supplies a mill, and further downstream, a nearly rectangular large cultivated area of 45 hectares, or garden. A rather strange dam (the garden dam) is built to capture water from the wadis that discharge downstream of the Harbaqa dam and to create a supplementary reservoir near the garden. Since the valley of the wadi is ill defined at this location, the ends of the dam extend in an unusual fashion along the edges of the valley (Figure 7.10).

The open canals downstream of the reservoir are earthen, but the hydraulic works and diversion gates are of stone, following the traditional practices of the region.

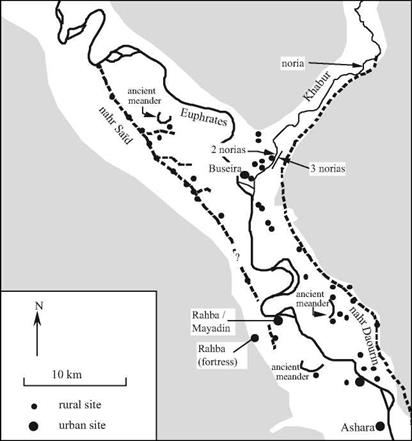

Mesopotamia becomes the granary of the great Arab cities. The entire irrigation system inherited from the ancient civilizations is carefully conserved, further developed, or put back into service if previously abandoned. The 35-km long grand canal called nahr Sai’d (Figure 7.11) is built on the middle Euphrates, apparently starting from the intake of the very ancient bronze-age canal Isim Yahdun Lim (Chapter 2). It brings water to the city of Rahba, founded in 820 on the riverbank by the Abbasids and subsequently relocated to the edge of the escarpment after an earthquake in 1157. This canal, along which there are several offtakes, is excavated into the plain. Therefore it cannot support gravity irrigation of large areas, as was done in the same region by the bronze-age canals.

This canal is instead used as a permanent source of water to be lifted into the gardens using saqqyas, remains of jars have been found there.[333] This practice explains why the region’s villages, all Islamic, are located directly on the canal and its offtakes. The nahr Sai’d is destined to be abandoned in the 13th or 14th century during the desertifica-

|

Figure 7.11 The confluence of the Khabur and the Euphrates – an area that is very developed from the 8th to the 12th centuries with the nahr Said for irrigation on the right bank and the grand navigation canal on the left bank (nahr Daourin) likely dating from the Bronze Age (Figure 2.7). The most downstream zone (where the ancient Mari was located) is almost desert in this period. Ashara is built on the site of the ancient Terqa. After Geyer (1990), Berthier and d’Ont (1994). |

tion of the region after the Mongol invasion (Rahba is abandoned about 1400).

The Raqqa region is further upstream on the Euphrates at the confluence of the Balih, and irrigated on the right bank from the Umeyyade period. The city of Raqqa itself, on the left bank, is an ancient Hellenistic implantation that was refounded by the Abbasid al-Mansour in 772. The caliph Haroun al-Rachid (the caliph of A Thousand and One Nights) especially develops the city during his residence there from 797 to 808. The

|

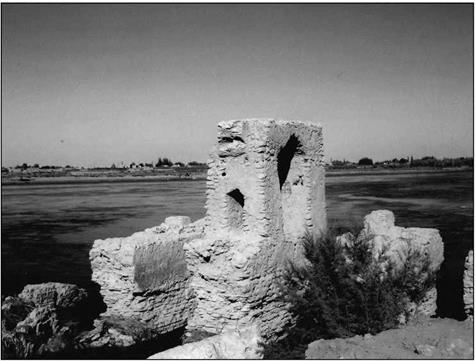

Figure 7.12 Vestiges of a noria and its mill at al-Lawriye on the lower Khabur. The photo is taken from the left bank, downstream; to the left, one can see the remains of the dam (photo by the author). |

city benefits from an extended irrigation network whose spine is a grand canal from the Euphrates, 10 m wide and more than 16 km long, called the nahr el-Nil.[334]

Navigation on the Euphrates is important from the Umeyyade and Abassid period up until the 11th or 12th centuries.[335] Rahba (Mayadin) controls an important fluvial port. The existence of Abbassid sites all along the ancient nahr Daourin (Figure 2.12) shows that this navigation canal is to all appearances brought back into service at this period.

On the Tigris, the nahr Awan canal services the new city of Baghdad, whose population in the 13th century is nearly a million and a half inhabitants. This grand canal, parallel to the Tigris, was built by the Sassinids, then enlarged and extended to capture water from the Diyala. In the 9th century a dam is built on the Adheim (or Uzaym) river, 150 km to the north of Baghdad. This dam, 15 m high and nearly 200 m long, feeds two new irrigation canals, the nahr Batt and the nahr Rathan. Like the other dams built by

|

Figure 7.13 Remains of a noria at Rweshed on the Khabur, immediately upstream of its confluence with the Euphrates. This noria had three identical wheels. At the left one can see the three canals and at the right, the remains of the aqueduct (photo by the author). |

the Arabs (those of Fars, for example), this structure is built of stones interlocked with lead seals.

During the 7th and 8th centuries the simple military camp of Basra becomes a true city with a new irrigation system fed by the Chatt al-Arab waterway, the common course of the Euphrates and the Tigris. According to al-Baladhori, a certain Hassan the Nabatian directs the drainage and irrigation works in this region. The “Hassan reservoir” at Basra is attributed to him. The first tidal mill is built at Basra in the 10th century to operate during the falling tide.[336] But despite these hydraulic works, the swamps of lower Mesopotamia cause Basra to be known for its unhealthy air and the “yellow tint of its inhabitants”, as described by Ibn Juzavy, the editor of the memoirs of Ibn Batthta.

In Arabia itself, particularly in the regions of Mecca and Medina where pilgrims congregate, numerous small dams are built on the wadis to provide water reserves through diversion of flood waters into basins and cisterns. There are some fourteen of these near Mecca and four in the region of Medina. The dams are from 2 to 11m high and 25 to 225 m long. The largest is the Qusaybah dam near Median, notable for its height of 30 m.[337] Certain dams in this region have inscriptions that would date them from the Umeyyade era. But some well-known travellers suggest otherwise. They attribute the water-resource development, needed for the caravans of pilgrims who cross the desert between the holy cities of Mesopotamia, to the queen Zubayda, cousin and wife of the caliph Haroun al-Rachid. Some descriptions of these watering places mention elaborate structures, not only the dams cited above but also the qanats when a permanent water source is found:

“Friday morning, we camped in a place called Birkat al-Marjum, where there is a basin for which they built, on the hill overlooking it, a pipeline bringing water from far away. The installation is perfect and shows how impressive human resources are and the great things that can be done with them. [….]. All of these basins, all the reservoir, wells, and rest stops between Baghdad and Mecca were developed by Zubayda, daughter of Ja’far ben Abi Ja’far al-Mansur, wife and first cousin of Harun alRashid. She devoted all of her life to this project.”[338]

The Arab cities, like the Roman cities, are major consumers of water – for baths, mosque hydrants, and caravanserais. According to Ibn Jubayr, Damascus has “nearly a hundred baths and nearly four hundred washing sites with running water everywhere” in the 12th century. Whether it be from their Roman heritage or from their Arab roots (like Rahba), these cities also have sewers.

|

Figure 7.14 Remains of an ancient noria on the right bank of the Euphrates, downstream of the Doura Europos escarpment, about 40 km downstream of Rahba (photo by the author). |

Catastrophes strike the Arab Orient from the 11th century on, and especially in the 13th century. Its population declines and farmland reverts back to desert or, even worse, changes into swamps like those of the lower Mesopotamian lands. In Syria the crusades cause an exodus from rural settlement beginning in the 11th century; however this exodus is partly reversed by 12th-century agrarian reforms that encouraged a return to rural agriculture. But then the great tragedy of the Mongol invasions occurs. We have already seen how Ghengis Khan had ravaged Samarcand, Bukhara, Marw and the cities of Khorassan. And now in 1258 his grandson Hulagti razes Baghdad (later rebuilt) and irreversibly damages the Mesopotamian irrigation system. The Ottoman era begins in the 16th century; Constantinople becomes Istanbul and is endowed with new water supply systems such as the Maglova aqueduct, constructed in 1564.[339] [340]

Leave a reply